I think there’s slightly more behind this post than old habits though, and that’s a suspicion I developed when I looked back at old blog posts, trying to get my head around where to begin; if not to find an echo of my old voice then at least to select a pitch that would resonate in harmony with it. I noticed some common threads, you see, when I looked back over those dispatches from my previous life. Art, yes, and various teaching practices, but arts and teaching practices that had in common a desire to create space for connection between people and communities. Spaces in which they could glimpse their shared potentials. Practices that were not afraid to recognise difficulties and divisions, but that aimed to forge something of an arena for those to be held and interrogated only so long as they were needed as a platform from which to recognise a deeper truth of commonality and shared humanity. How close those ventures ever came to achieving that is not for me to say but it’s with a similar aspiration that I seek to share my recent experiences

If you’re new to, or never much followed this blog, I’ll fill you in a bit. I left a life of arts practice and teaching in 2015, after learning to meditate to try and manage stress and anxiety. When I went on to I learn about the teachings of the Buddha I felt I had found a new, clearer and somehow more honest way to try and live my life with integrity. I’d always tried to realise an ethically robust existence and I’d always believed there was little point in having a life if you weren’t going to try and make the world a better place with it, but I’d never before found such a simple and direct model by which I might try. So now, heading on for 5 years later, I am living in a community of ten women in rural Shropshire who run a retreat centre for other women to come and learn the same. Taraloka Buddhist Retreat Centre for Women is part of the Triratna Buddhist Community and it is with that global movement that I am training for ordination. Not a turn I necessarily expected my life to take but if I’ve learnt one thing in 38 years on the planet, it’s to expect the unexpected.

So, in a life fully committed to making the world a better place by helping women find happier lives through the teaching of the Dharma, what on earth would attract me to spend two hard-earned days off prowling the streets with XR? In my late childhood and early teens I’d been involved with various direct action groups from local to national level, and been passionate in my belief that such efforts could change the world. I leafleted, I petitioned, I lobbied, I made personal life style changes (to the derision of many peers and family members), I joined marches, I attended rallies, I even risked arrest. I felt for a time like I had tireless reserves of energy to pour into preserving the world for the common benefit of all species living on her and I believed that once everyone was appraised of the global injustices that were only too clear to me then the job would be done, for who could continue on that path of ecocide if they truly knew the impact of their actions? Of course what I wasn’t prepared for, or equipped to oppose, was the equally bare truth of greed, hatred and delusion, threads of which can be found in all of us. I over identified in the success of the campaigns I aligned myself with, felt increasingly inadequate in the face of ever more depressing news and became utterly disillusioned upon encountering infighting and disharmony in those groups through which I sought to affect change.

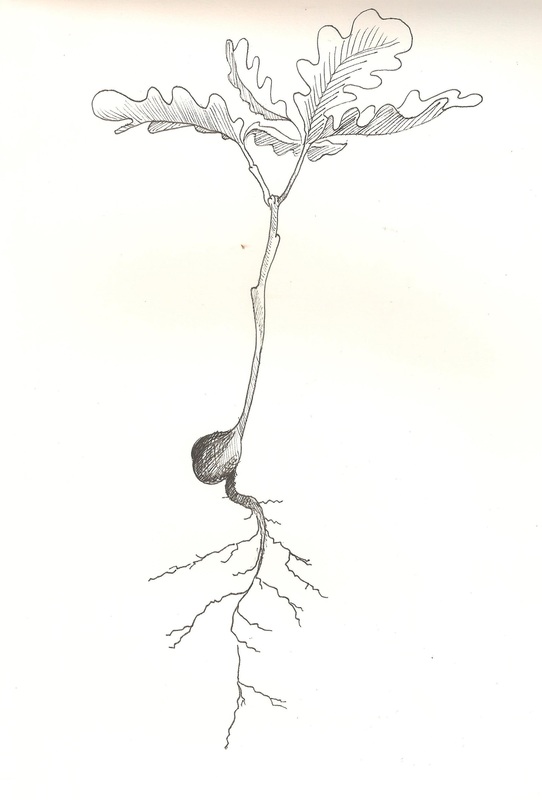

So, it’s perhaps no wonder that I eventually resorted to tamer, more socially acceptable and ultimately institutionalised ways to try and do good in the world. More recently however, since beginning to question the true potency of those ‘safer’ channels, I’ve felt a stirring in deeper, more rebellious roots and started to see that with a spiritual practice behind me I might once again engage in direct action, sustained so that I can still come from a place of heart-aching compassion but balanced with the temper of a wider wisdom. I’m not alone in this either. I’m not sure I’d have jumped on a train and headed down south without knowing even where I’d sleep that night if I’d not known there was a sangha of Buddhists from various traditions all planning to do the same, and they as part of a wider interfaith movement. The plan was to add our voices to those of the Extinction Rebellion chorus but especially to support the planned daily meditations and uphold the non-violent principles of the XR movement.

| Recently XR has been making training in NVDA (Non Violent Direct Action) available in various towns, at events and even through online webinars. I attended some this year at Buddhafield Festival. Though I wasn’t particularly planning arrest, I couldn’t see any harm in getting an update. I’d been coached on the wisdom of silence in custody decades ago; No Comment was a mantra I’d learned at about eleven, but having since heard this could be used as evidence of admission to guilt in court, I wondered, was that still current advice? |

Last October, when I visited the Preston New Road anti fracking camp and spent time chatting with resident campaigners monitoring the Cuadrilla site gate, conversation had soon fallen to their experiences of heavy-handed law enforcement. I’d known at the time that such confrontations would be frequently exacerbated by a (perhaps not entirely unjustified) tendency to vilify and mistrust the police and that such a divisive mind set could ultimately only bring trouble. I also knew how easy it would be for me to fall into a tempting trap of hate and prejudice myself. Hate breeds hate but love and understanding are not easy to stay in touch with during moments of heightened emotion and physical threat. Nonetheless, it was with an aspiration to keep the Buddhist precepts of non-harm, generosity, contentment, truthfulness and mindfulness close to heart that I packed a minimal bag with plenty of snacks, no ID, and a newly acquired not-very-smart phone before boarding the train to my old home town. I’d also just learned that the Preston New Road ‘Nanas’ had been successful in finally bringing an end to fracking in Blackpool, so a renewed confidence in the power of direct action gave me an additional spring in my step.

I arrived in London at about five thirty PM on Monday the 14th of October, the first day I was free to get there but the start of the second week of the rebellion. That was the day when activists had focused on the Financial District and blocked the roads at Bank. When I’d booked my train ticket, I’d imagined myself heading to Lambeth Bridge, where the Interfaith community and the XR Buddhists had originally planned to be but I knew from checking the XR website before I left that the camp had been cleared by police pretty quickly and that they were now based in the one bit of London where the protests were being tolerated: Trafalgar Square. I went straight to the faith area when I arrived and spotted a bright purple XR Buddhist tent immediately but it was empty so I ambled up to a small group sitting and chatting under a nearby gazebo. Since I was hoping to spend the night there, it seemed natural to introduce myself. I was quickly informed that a ‘congregation’ had just begun at St Martin’s in the Fields so I headed straight over. I didn’t expect to be ushered in by a police officer and didn’t quite know how to take his comment that they wouldn’t notice I was late.

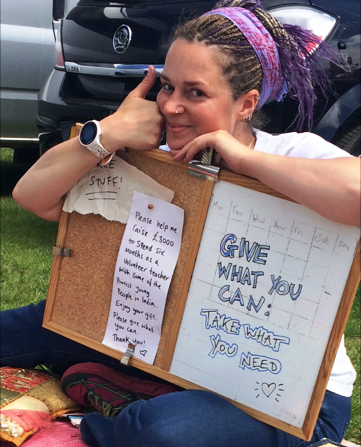

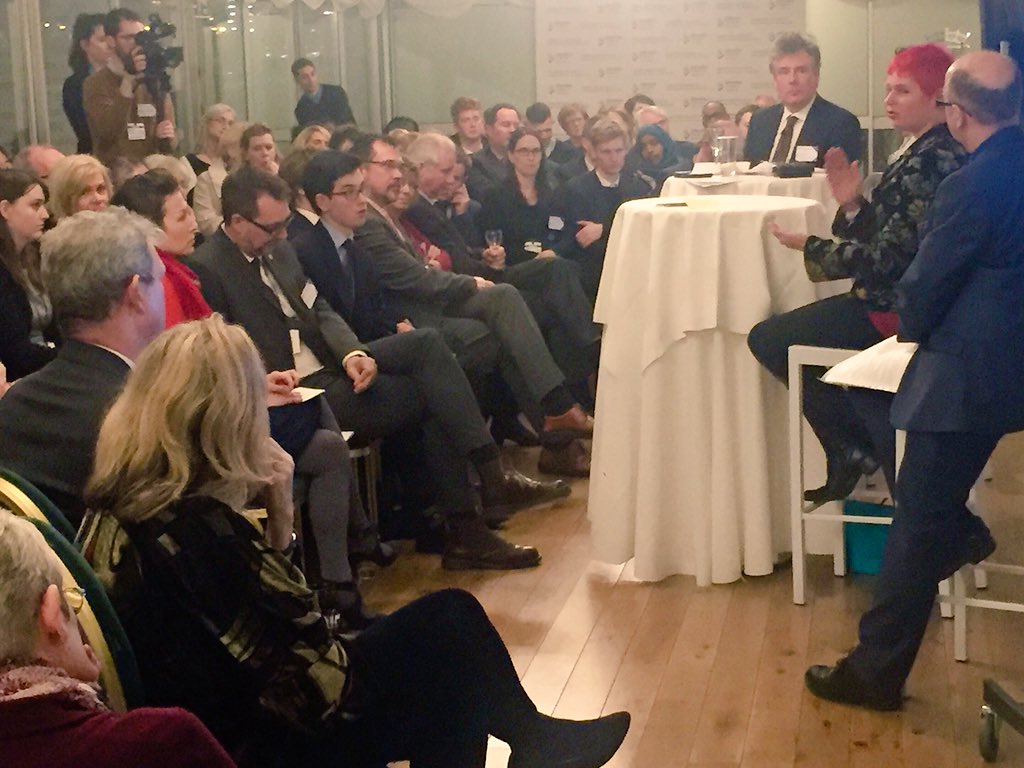

I soon learned that the congregation was in fact a People’s Assembly, a collective decision making strategy used by XR that aims to ensure everyone gets a say and no one dominates. I quickly agreed to be scribe to my group; I’d had a go at group facilitation at an assembly in the summer and didn’t think I wanted that responsibility so quickly but was fairly sure I could manage note taking. The assembly initially questioned the wisdom of maintaining a presence in Trafalgar Square and upon establishing a consensus to do so, continued on to look at ways that presence might be facilitated effectively. The symbolism of the place was not missed in terms of the history of political demonstrations in the square and recognition that it could be a prime location for engagement with the public. It was agreed that opening the space outwards and making more efforts to invite speakers as well as performers would be positive steps in maintaining a purposeful presence throughout the week. The lead facilitator and note taker would take that back to organising teams to implement, but there was a sense that everyone in the room who would have any sort of presence in the square would take their share of responsibility for enacting it however they could. Some other ‘housekeeping’ points were discussed, such as how to helpfully interact with the local homeless community in whose living room we’d essentially deposited ourselves, how to ensure the no alcohol or illegal drugs commitment (Rebel Agreement point 4) stayed firm and an concensus on appropriate times for ending amplified music and other sources of noise. Things just seemed to be wrapping up nicely and I’d determined a ‘next step’ for getting involved (head to the welcome tent and sign up for voluntary stewarding or cooking slots) when the part of the note takers role I’d not clocked became clear to me; I’d now have to stand up in front of quite a large room of strangers and attempt to summarise the salient points in the discussion of about ten other people I didn’t know based only on the strength of my notes. For not the first time in my life, I appreciated all my years of teaching experience as well as my more recent dabbling in spoken word and fairly leapt up to confidently (ahem) précis ninety minutes of detailed discussion. I opted mostly for the positive bits that stood out to me, as well as the points hastily whispered by those who seemed more experienced. Anyway, it seemed well received.

I left the restrained panic of the welcome tent (I had, after all, learned one updated fact from my recent NVDA training, which was that if people started talking about sections and numbers, it was best not to hang about to listen) and headed back to the faith area where some ruffled Christians were attempting to pack up. Vaguely presided over by a worried looking vicar who clutched a rhinestone studded, ply wood cross bigger than he was and looked like he might at any moment burst into tears, they were piling things they knew belonged to their group in a central heap, where they hoped it would be collected by someone who had managed to park a car not far away. I offered to help. Time was ticking and it was clear no one had any chance of clearing the square fully within the hour. I hadn’t done much more than fold some camping chairs in what I hoped was a helpful way, when one lady asked where I was staying that night. I vaguely gestured at the purple tent. ‘Probably not there anymore!’ I conceded. Apparently deciding my accommodation was of greater import than the camping chairs, she quickly led me out of Trafalgar Square and to a Quaker Meeting House in an alley off St Martin’s Lane, where thanks to her introduction and after leaving only minimal details, I was very glad to give the warden £10 straight away for two nights on their floor, though he seemed embarrassed to accept it and tried to suggest I should pay when I left. I was able to leave my bag there then and so headed straight back to the square, unburdened in more ways than one and willing to get stuck in with whatever was needed.

| There was an even heightened degree of confusion by the time we got back, prompted at least in part by the police starting their own process of ‘packing up’ the camp, which seemed to go something along the lines of vaguely asking the nearest person if they knew who certain items belonged to before dragging said items away with no further enquiry. It was raining by now and so those of us still in the faith area were sheltering under the Christian’s gazebo with their possessions while they waited for the car, which they knew would be too small to fit everything in. |

Painful as it was to watch, I tried to keep things in perspective. We were not, after all, reliant on these structures for shelter or protection, unlike the millions of political and climate refugees who have been forced to leave their homes. We had all chosen to be there and had alternative places to be. Nor were we in physical danger from the police, who, I carefully reminded myself, were doing jobs they had probably taken from a desire as genuine as mine to make the world a better place in the only way they knew how. Despite the sense that we were witnessing an erosion of our right to protest, we were not being persecuted for our religious activities, unlike many the world over and did not have to hide our political beliefs or our cultural backgrounds. Most of us there had white faces, educated accents and the privileges that come with these features. What I experienced as oppression would probably appear like the fullest expression of liberty on a global stage.

Once the faith tents were no more, I felt free to lend a hand elsewhere and accepted a bin bag and a heartfelt instruction to ‘leave no trace’ from a steward. By this point it seemed that some sort of cooperation, if a slightly suspicious and reluctant kind, was emerging between protesters and police. We were there, after all, to raise awareness of the threat to life from environmental destruction, not litter the capital and desecrate a national monument (whatever your views on British military history might be). Small things of no value and scraps of litter went in the rubbish bags. Full ones were tied off and handed to police officers. Larger items that could not be so easily dealt with needed only to be drawn to their attention for disposal. I did actually try and help one officer carry two wet sandbags but was eventually glad to let his colleague take over since I was also still clinging to the bags from the Buddhist tent.

During all the activity, information was shared in a couple of ways. Individual stewards were moving through the crowd, dispensing bin bags and speaking to people to ensure everyone was either accommodated for the night, or knew how to get to one of the arranged sanctuaries. There were also frequent ‘human microphone’ announcements; a surprisingly effective method of addressing a crowd, relying on the amplification of multiple voices repeating a message announced by the call of ‘mic check!’ Practical information and gently calming reminders that police were doing their jobs and there to look after us, were all broadcast by this method.

After a bit of a breather, in which I managed to avoid arrest ‘on suspicion of loitering’ by determinedly fiddling with a stray bin bag in a totally nonsuspicious way that clearly communicated I was actually full of purpose, we received news that a van was coming to collect unclaimed items and store them as lost property. I was busily engaged in a team of people trying to move a small garden that had been planted on a sheet of tarpaulin to the van, when I was absolutely delighted to be greeted by the friendly face of someone I actually knew. ‘I won’t disturb you!’ she said emphatically, ‘I can see you’re busy!’ I took advantage of a pause for breath in the garden rescue squad (wet compost is heavy) to engage in conversation. She was keen though, she told me, to rush off herself, as she’d only just heard that the square was being cleared and had come to see if she could salvage anything from the Buddhist tent. ‘It’s here!’ I intoned darkly as I handed over what I knew to be all that remained. I wasn’t sure what was more enjoyable, the look on her face when I passed it to her or the fact that I now had two hands free to try and lump wet mud and wilted begonias across Trafalgar Square. We quickly swapped numbers and she told me of a 07:30 breakfast meeting round the corner where we could catch up properly. I was then back to my botanical philanthropy and she disappeared into the night. Freed once more from baggage, I kept going as long as I could. A wheelbarrow of camping equipment here, a box of random items there, a giant teddy bear, a sack of I know not what. Of course it was the police who were reported in the minimal media coverage the next day to have ‘cleaned’ the square, and had we not been so thorough it would no doubt have been the protesters at fault for littering but there have probably been worse misrepresentations of direct action groups in the press.

I don’t know how long those who did choose to lock on to tents and gazebos managed to stay put but I guess not long. Temporary structures don’t afford much anchorage. Eventually curtailed by my exhaustion and a looming 11:30 curfew at the Quaker Meeting House, I left the ongoing clean-up operation at Trafalgar Square wryly mindful of the signal sent by Nelson, from the HMS Victory 214 years ago and recorded at the base of the column; ‘England expects that every man will do his duty.’ I might certainly stand accused of a rather unconventional patriotism and not one to everyone’s taste but the earth of this land is in my flesh and I am proud of certain aspects of my national history; especially those that have found expression through my political ancestors who have fought generation after generation for a free and equal society. I see Extinction Rebellion as a continuation of that vision and I believe it is only in social, as well as systemic reform on a global level, that we stand any hope of facing the peril of ecological collapse. I believe I have a duty to this planet and the life on her and I believe I have an obligation to responsibly utilise the privilege that I unwittingly inherited when I was born in this country. An ideological descendant of Emmeline Pankhurst, I may well wince at the outdated gender bias of such a statement and I would reject outright any suggestion of military glorification but as I lay myself down gratefully on the floor of the meeting house that night, I certainly knew I had done my duty and felt resolved that I would continue to do so in the morning.

As I tried to get comfortable on the hard floor, hands still sore and filthy from the clear-up efforts and surrounded by the unfamiliar squeaks and snuffles of others also struggling to sleep, I reflected on why I felt so shaken by my recent experience. It wasn’t actually a perceived threat to my right to protest that I found most painful about the clearing of Trafalgar Square, nor a sense of disrespect or sacrilege to the religious groups, though I dare say they would have been justified feelings. The thing that caused my sadness more than anything else was the apparently gratuitous interruption of harmless community activities, peacefully carried out in a spirit of love, care and inclusivity for the benefit of many. The strong arm of the law, the voice of a system I believe to be powered primarily by greed and fear, snuffing out this flame of hope at the first possible opportunity. This living beacon of the way we might all live more connected and less harmful lives, denied a chance to fully shine and (call me a cynic) probably only because the Financial District had found its nose put out of joint. Yes, I might be a dreamer too but I’m not the only one either. I’m not sure I did actually dream that night but I eventually managed some broken sleep.

| I think there were about ten of us that met the next morning, clutching our re-usable coffee cups at a café round the corner from where I’d slept. We weren’t the only affinity group there but after a quick hello we kept to ourselves. Those with access to the internet had established that the main planned action that day would be on Millbank, outside MI5, to highlight that the biggest threat to national security wasn’t being truthfully communicated to the public. |

There were six of us that each wore an A2 sign bearing a photograph of the planet from space and the words ‘Grief and Love for the Earth’, walking in a line from Charing Cross station, chanting Maitreya’s mantra. I realised that there was a strand of fear running through me, just from engaging in in something so incongruous in that public place. I’m pretty confident that a large proportion of me doesn’t much mind what conclusions strangers care to draw about me or my fellows based on how we choose to display our religious convictions and yet there’s still a part that would really prefer not to stand out too much. One never knows what seemingly innocuous act might draw the wrath of another, nor how they might decide to communicate that to you. Still, I tried to keep my purpose in mind and feel into a meditative experience as we navigated amongst busy pedestrians and waited at road crossings. If nothing else, I told myself, the intention of walking through these troubled streets in awareness and love for those struggling on them, even aside from the wider planetary situation, can’t cause harm and might in itself be beneficial in a world where we're more connected than we can ever understand.

I didn’t have to endure the discomfort of public exposure for long, however. We barely made it to the south east corner of Trafalgar Square before we’d been stopped and detained, despite clearly communicating our intentions to keep moving past in a walking meditation, which had been given the go ahead by a different group of officers further up the square. We were immediately informed that we were in breach of Section 14 of the Public Order Act and as such we would now be searched for evidence that we were planning criminal damage. Thankfully the short burst of meditation must have done something for my mental states and I wasn’t feeling argumentative, else I might have pointed out that as I understood it, Section 14 of the Public Order Act actually related to assemblies, whereas this was clearly a procession and would need therefore to be a breach of Section 12 of the Public Order Act, which I didn’t believe to be in force. I could sense an air of confusion and high stress amongst the police, however and decided that an ‘importunate nose ringed climate change protester’ telling them their job would probably only aggravate matters for all concerned. I therefore felt content to allow my two-day picnic bag to be unceremoniously rummaged through while I quite truthfully allowed it to be known that I had no ID with me, no, not even a bank card, and did not at this time choose to share my personal details though it had been nice chatting about my sandwiches, thank you. We were then informed that in order to avoid arrest, we would need to leave the square in different directions. I noted with interest that it wasn’t until that point that I actually felt particularly intimidated. Until that revelation, it had all felt fairly harmless. I once got stopped and searched for carrying a worm compost bin across Stratford Station concourse and that hadn’t resulted in any legal side effects. I was not especially surprised that we’d been told to stop chanting and wearing our placards either, though I was far from certain of the legality of that demand. Being suddenly denied the company of my friends however, felt like a whole new level of fear tactic, a deliberate alienation, a divide and conquer strategy. I see myself as a pretty independent person who is no more fazed by the streets on which she grew up than by the prospect of time alone but it’s never once occurred to me that I might be denied a choice in the matter and it seemed a disproportionate demand. We hadn’t been gluing ourselves to buildings, nor defacing monuments. The forced search of our persons and belongings should have demonstrated that we weren’t ‘going equipped’ for such acts either. We’d been engaged in a walking meditation, whilst chanting a peaceful mantra and wearing signs expressing an ideal of love.

My new found isolation didn’t last any longer than our ill-fated meditation and one of my friends drew silently alongside me as I crossed a road. Via a farcical scene involving veiled gestures, feigned absorption in text message conversations and a studious appraisal of the local bus timetable, we managed to each catch sight of one another and re assemble in, horror of horrors, an international public toilet chain that frequently tries to sell rapidly prepared food-like substances to users of its service. Someone bought a couple of limp, oily hash browns to justify our presence there which is frankly more than I’d have done but perhaps that was only fair to the establishments workers. Of course, the premises was itself full of police, but not the ones who’d separated us, so we seemed relatively safe, if unsettled, in our reunion.

We were all a bit rattled and slightly spooked but found some comfort in sharing those feelings and soon agreed that what we really needed to do now was to find a spot where we could actually do some meditation practice as much for our own wellbeing as anyone else’s. We set off in pairs to avoid detection and reconvened under a tree in St James’ Park, where we decided to ritually transfer our merits for the benefit of all beings before a twenty minute sit. We’d then hear a reading of the Shambala Warrior Mind Training before heading back out to various activities; work for some, further direct action for others. As we settled to this, one of the group warned that our circle was being approached by police so we continued reciting the Transference of Merit with trepidation. We must have appeared less threatening on closer inspection however, and we were left in peace to our much needed meditation.

Allowing my attention to rest in the soothing sound of wind in the leaves above us and the sensations of the breeze on my face for some time was indeed nourishing and I could feel a calmness return to me that had been steadily compromised over the course of the morning. The words of the reading drifting into my awareness then galvanised me and reminded me of my purpose. ‘Do not set your heart on particular results.’ They coached. ‘Enjoy positive action for its own sake and rest confident that it will bear fruit.’ Those sentiments were moving enough in themselves but there was one line in particular that stirred a tear to begin its own procession down my cheek. ‘When forces of power seek to isolate us from each other, reach out with joy.’ We ended our meditation, shared a few snacks and went back out into the city in different configurations of two to continue our quiet but deliberate attempts to peacefully affect positive, global change for the benefit of all life on Earth.

| My new partner and I enjoyed a bit more of a catch up than we’d managed previously as we headed off through the park towards Millbank. We were unsure of exactly what we’d find, or if we’d be able to meditate there but we anticipated separation and agreed a café to meet in, should the inevitable happen. As we headed up Horseferry Road towards the junction with Millbank, we passed two semi supine male protesters in the road, locked on to one another through a piece of pipe. |

Our friends had heard of an impromptu midday flash mob cum protest at Trafalgar Square in defiance of the move by the Met Police to ban all Extinction Rebellion demonstrations in London and we agreed from our experiences that morning it was something we would be keen to add our voices to. We didn’t have long to get there as it was only a few minutes to twelve so we charged off down the way we came and back past the two activists still slumped uncomfortably on the opposite pavement. It can’t have been more than a hundred yards further up the road that we encountered a similar roadblock. Two men, locked on to one another and sprawled awkwardly over a wheeled suitcase in the middle of a pedestrian crossing. One was loudly and calmly shouting details and sources of recent scientifically accepted findings on the causes and impact of climate change. There was a ring of police around them and an outer circle of concerned or at least curious passers-by. One of our friends who had that morning announced himself to be arrestable took the decision that this was his moment to make that statement. He handed his bag to the rest of us for safe keeping and calmly stepped through the ring of police who were apparently there to contain the activists who clearly had no intention of going anywhere anyway. With clarity and deliberation, my friend drew his kesa from his pocket (an ordained member of the Triratna Buddhist Movement wears an embroidered strip of cloth called a kesa about their neck to symbolise robes during order gatherings and ritualised practice) and sat in the road beside the lock on.

| I found that act deeply moving and witnessing it shifted my own consciousness from a place of mundanely watching a roadblock to one primed and ready for spiritual practice. For the benefit of all beings. Because I would not choose for there to be suffering. Because there can be no Dharma on a dead planet. The three of us still standing on the pavement sat together on the kerb without a word to arrange ourselves there and began to meditate. |

I had no inner sense of how long I was there for and I’d say it was one of those moments where conventional time seems meaningless but in thinking back I now estimate that we can’t have been there more than perhaps five minutes. I became aware of my friend beside me starting the Padmasambhava mantra, a deeply beautiful sound of steadiness and strength. I hadn’t the chance to join the mantra for even a full recitation before a new sense impression crossed my consciousness. I was for the second time that day being formally notified that my meditation was in breach of Section 14 of the Public Order Act. The voice continued to inform me that unless I moved immediately, I would be arrested, which would in turn jeopardise my future career and travel prospects as well as result in court fines and charges. The owner of the voice had clearly misjudged what I might find threatening for I was not perturbed by the risk of difficulty finding employment in a system I have already chosen to unsubscribe from as far as I can, nor was I concerned about a further reduction of my freedom to roam a globe that is scarcely open in its borders as it stands. As I listened to the voice edging syllable by syllable closer to the point at which my freedom would be temporarily denied me, I became aware that I was listening from a place of uncommon clarity and fearlessness. I did not feel afraid. I was not physically in danger or at risk from the bureaucratic process my arrest would initiate. I could have chosen at that time to join the ranks of those facing arrest to make a point about the imminent threat to life on this planet, and I could have done so at little personal cost. There’s one place in my life though, where I could see the potential for negative repercussions and that was back at home, in the Taraloka community. That’s not to say I didn’t think I’d be out of the cells in time to catch my train home and return to work in the retreat centre the next day. I didn’t even imagine it would be impossible to negotiate the days I might need for a court hearing. If I was charged, I believed I would be able to cover what I anticipated would be a small fine without needing financial support from the community. But I could see it would have deeper repercussions than that and I didn’t feel sure I was in a position to know what all of those would be. I had left home the day before clearly reassuring people that I did not plan to be arrested and going against that now would be a direct breach of a trust I honoured. It might also appear to question the extent to which I prioritise and value the world-changing work of Taraloka above any other activity I choose to align myself with. I didn’t know, but it could even threaten the integrity of Taraloka herself. What benefit I might achieve by allowing myself to be arrested at that point did not warrant the potential harm I might cause my community in doing so. Difficult as it was for me to leave my XR Buddhist fellows, I had made it clear to them that morning that Taraloka was my priority and this was the point at which I was required to stand by my assertion of that primary commitment.

Again, I’d be unable to guess how many seconds it took me to internally churn out that thought process but it was thankfully quicker than the spiel that was being outwardly directed at me. I continued chanting but opened my eyes, slowly stood and bowed deliberately towards those still engaged in the road block before stepping out of the gutter and back onto the pavement, honestly believing that my retreat would be enough. The voice continued to advise me that I would now need to ‘turn my back and walk away’ to avoid arrest. Turn my back on my friends. Turn my back on my beliefs. Turn my back and walk away from my right to speak my truth. Be a deserter. Be a coward in the face of oppression. My inner teenage rebel stormed in the depths but I met her with further words from the morning reading. ‘When you see weapons of hate, disarm them with love.’ I turned to make eye contact with the owner of the voice. I allowed myself to take in their mottled greyness and looked beyond the lines of historic pain and laughter that fringed them. I allowed the police uniform to fall away from my awareness until I was looking directly and compassionately at the human being beneath. I allowed myself to become equally liberated of assumptions and stereotypes and to stand once more on the level playing field of fragility and suffering that I’d not long left behind. ‘Sit with hatred until you feel the fear beneath it. Sit with fear until you feel the compassion beneath that.’ I stopped chanting and held out my hand. Confusion and uncertainty passed across the eyes I still held in my gaze but eventually the response came. We shook hands. ‘Thank you.’ I said before once more folding my hands at my chest and walking alone down Horseferry Road, continuing to chant the Padmasambhava mantra with not the least thought to the judgements of the public bustling about me.

At the next junction, and when I believed myself to be free from the risk of arrest, I crossed over and went back towards the roadblock on the opposite side of the road. I could see my friend had by then been moved away from the crowd and was in the process of being arrested. I could see my other two friends who I’d been sat with now standing slightly back from the kerb in something of a huddle but I couldn’t see any more than that easily and didn’t want to be too obvious so I carried on past and bought a cup of tea in our pre-arranged rendezvous café. It was about twenty past twelve by that time and I felt quite ready to sit down and do nothing for a bit. I waited until gone one before walking back past the roadblock. It was still in place but I could see no one I knew. Assuming the worst and realising I was by then quite hungry, I sat on the riverfront in Victoria Tower Gardens and disconsolately ate a day old sandwich. I felt strangely alone, slightly traumatised and very vulnerable. I decided to head towards Vauxhall, where I believed there was still something of a camp, though I also knew most of it had been evicted, despite having had permission from the local residents association to be there.

| At least I thought I might find someone who could update me a bit with what was happening. The printed press was sharing very little it seemed and I had no internet access to check other sources. I decided not to try and cross Lambeth Bridge as anyone who looked vaguely alternative was being denied access and I hadn’t yet regained enough of a constitution to challenge that but I thought if I got further away from the centre of town I might be better able to get peacefully to the other side of the river. |

By that time, we’d got word that our intrepid comrade seeking sanctuary out in Bethnal Green had no way of paying for a sorely needed lunch, having left her bank cards with another friend in Vauxhall. We packed up the banner, said our farewells to those who remained, and three of us set off across town on a mission to feed the needy. I think we all benefitted from spending some time simply hanging out together, in a normal sort of way, as you might expect to do with friends and there was indeed something of a relief in being outside of Central London and the imagined gaze of unknown eyes. After some recuperation time just being together, we started to make a plan. We called the XR back office helpline and they managed to ascertain for us that our other friend had been taken to Acton Town police station. It would be necessary for us to go our separate ways again, but that’s a lot less difficult when you’re at liberty to say your farewells. We walked up the road to the station where one of us would be able to get the train to a safe house for the night and where her bags had been taken for her following the eviction of the Vauxhall camp. The three of us remaining also went on to our different evenings; one to some well-earned rest in her community, one to Brixton police station, and me, with our friends bag, to my mission in Acton Town.

I arrived at Acton Town police station at about 19:30 and found a fairly jolly, if somewhat sober scene. A knife amnesty bin in the waiting room had been heaped so high with various snacks and treats that its original purpose could barely even be made out and a small forest of juice bottles and flasks populated its base. A group of excited teenagers were gathered outside waiting for a friend but they were very happy to direct me to the official XR Arrestee Supporters inside. A bizarre yellow telephone like the ones you see at emergency call points on the motorway allowed me to make contact with the custody suite and establish that my friend was indeed still there so I sat down to wait. I exchanged some almonds for some walnuts with one of the XR team and we chatted a bit about our experiences. After some eager anticipation from his friends and a very proud dad, one young man was released in to their warm congratulations. Happy as I was to witness their reunion, I sadly reflected how unlike the experience of many young Londoners that would have been. I only needed to wait about ninety minutes before my own friend emerged, looking a bit dazed and very confused by all the eager volunteers springing forward to offer him snacks. He gratefully and politely refused, explaining that actually, he’d only just eaten. I stood back to ease the crowding and waited while he accepted a post-arrest advice sheet and volunteered information to one of the XR team about his arrest experience. I was glad to hear that he felt himself to have been well treated and had no complaints. I don’t think it was actually until I managed to communicate to him that I had his bag that he recognised me; we’d only met that morning and I can’t say I was surprised given the excitement in the waiting room. After making a call home to reassure people of his release we thanked the support crew and headed back towards the Underground, to travel back into town together and spend the journey sharing our experiences. All things considered, reuniting my friend with his bag and being a (vaguely) familiar face to greet him seemed to have been the best possible thing I could have done with my evening and I was equally glad to receive the news that our other friend had also been freed. We arranged to meet near Tottenham Court Road for a slightly later breakfast meeting the next day and I was back at the Quaker Meeting House just in time to use the room that was only available from ten PM. I slept much better that night.

My train home on the 16th left Euston at 11:40 so I really couldn’t risk being delayed but I was keen to make the most of my morning to support the ongoing efforts of the XR Buddhists Affinity Group if I could. There were just three of us who met the next morning, but there would be more coming for other planned actions later in the day, so our little trio contented itself with a twenty minute street meditation under a dry(ish) part of the entrance to Tottenham Court Road Underground station. I sat for as long as I felt able, trying to feel open and engaged with my meditation and the street around me, but aware of the building pressure of my imminent departure, I found it hard to concentrate. It felt only slightly strange and perhaps entirely appropriate to get up and finally leave my friends as they continued to sit in meditation on the cold, wet pavement.

I had cut it a bit fine but I caught my train and collapsed gratefully into the reassuringly predictable dullness of the long journey. I listened to some music and tried to enjoy watching the world flick past the window but I began to feel nauseous (I don’t get travel sick) and couldn’t relish the inactivity as I usually do. I allowed myself to shed a few tears and began to reflect on the nature of what I’d experienced. From our position of privilege in the global north, it’s easy to hear the words ‘Climate Emergency’ as though they’re some kind of distant rhetoric but I really did then begin to feel that yes, this is what responding to an emergency feels like. Reduced comforts, living from moment to moment, thrown together with strangers and trying to respond practically to every situation based on no more than need and capacity. Sometimes separated, isolated, alone and afraid, not being sure where the next threat will come from. Making do with only what I could carry with little choice but trusting to the outcome of my best intentions, less question of me and mine and choosing instead to think of us and ours. What have we got? What do we need? I felt so proud, grateful and humbled to witness my friends, many of them new to me, putting themselves in the line of power and making themselves afraid and vulnerable all for the love of this planet and her beings. ‘This’, I wrote in my note book ‘is our work. This is our Dharma practice. This is for the benefit of all beings.’ I know not all opinions are united behind the current debates around how to address our globally precarious position and I know not everyone has sympathy with the methods of civil disobedience Extinction Rebellion is choosing to use to try and raise awareness of our plight. I don’t believe either that it’s the only way to achieve change or that engagement with it doesn’t come with weighty responsibilities. There are a hundred other, equally direct, and less disruptive actions that we also need to take as well as to somehow find our way to a consensus on the social and economic overhauls we’ll collectively need to make in order to move forward not just as a species but as a living planet. In sharing these experiences I am not claiming ethical superiority or assuming that I preach from some kind of moral high ground. I am not trying to tell others how to lead their lives or oppress different perspectives with my privileged lifestyle choices. But I am trying to share, because I believe it is by listening to each other and by being willing to speak that we begin to understand and not fear those with different views. I believe love and understanding are perhaps the most potent tools we have as a unique and sometimes tragically powerful species. If nothing else, I’ve often been told that my writing is engaging and can give expression to the views of others who wouldn’t have felt able to articulate their thoughts themselves. So I guess that ultimately my motivation for writing this piece is in respect of another of lines in the Shambala Warrior Mind Training:

‘Following your heart, realise your gifts. Cultivate them with diligence to offer knowledge and skill to the world.’

May my offering benefit many.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed