If my last couple of updates have seemed relentlessly positive then good. There indeed continues to be a great deal to feel very positive about. There was also; however, an ongoing situation underpinning my experience of that positivity, that I found quite frankly, less than pleasant. Thankfully, it is increasingly distant, but in the interests of maintaining an entirely honest record of my time in India I feel obliged to record it, despite its rapid recession.

If you’ve been regularly following my blog, you’ll recall that though generally, my health has been good; I’ve been enjoying the cuisine (spicy food does not upset my system) and doing my best to stay physically fit and healthy (I joined and have been using a local gym as well as maintaining some yoga practice), I’ve not had a completely spotless medical record. In November, I had what appeared to be my first bout of food poisoning. This was embarrassing but no worse; it’s perfectly possible to eat something dodgy in the UK, in fact I distinctly recall a particularly evil houmous sandwich that once knocked me out for over 24 hours. Then, on our way back from Bihali, I was flummoxed by what was apparently my first ever experience of car sickness. We decided this was probably a combination of fatigue, altitude, a full day in the car on winding roads and too much lunch. Whatever. Such is life. I recovered.

I didn’t recount the details in the recent update on our trip to Raipur, because I didn’t want to undermine the important facts about the visit; namely the students, but actually that had been a pretty wretched experience for Mark and I. Mark felt ill before we left, and became sick as we arrived in Raipur, so, when I was hit for a third time, it seemed irritating but inevitable. I must have caught the same bug or virus. It took me a little longer to get over that one, but I flopped back, even if ‘bounced’ back would be a little exaggerated. By the time the following weekend rolled round, I was feeling 100% and rather perky. I was bouncy for enthusiastic participation in the New Year party and the inauguration celebrations the next day. After the ceremony, I energetically delivered a presentation for our students on my experiences and learning at the NNBY convention. I had an important message to communicate and seemed to achieve this well.

Quite literally the minute I finished delivering this, as I packed away the projector and laptop, I was overcome with a wave of nausea and fatigue. I had to sit down to finish putting the equipment away but I got out my notebook and dutifully attempted to participate in our scheduled teachers meeting, to plan the content of the coming week. Feeling faint, I had to lie down instead. About ten minutes later, once again, I said goodbye to what had been a lovely lunch as I succumbed to sickness for a fourth time. Now, those who know me well will know I tend to the self-medicating. If a bit of me has not actually dropped off, I do not like to trouble myself or medical staff with my ailments. This is especially true when I am very far from any familiar healthcare providers and am not actually sure exactly how to go about accessing it. As I stared up at the spinning ceiling; however, I couldn’t help wondering if there might be something a little more to an inconvenient but apparently unrelated string of maladies. Perhaps, I thought, it was time to seek some medical advice.

Later that day, after I’d rested enough to feel like could walk, Mark and one of our more confident, English fluent students, gave up their evening, to my eternal gratitude, and came to help me find a doctor. The first place we visited, the Dr Ambedkar hospital, was closed. The rickshaw driver who had taken us then suggest and dropped us at a different clinic, which had no doctor available for another 90 minutes. Mark thought he knew where there was another place as he’d seen people queueing, so we trudged round the corner. Lo and behold, third time lucky and we were shown into an examination room to wait.

Now, I hate hospitals at the best of times, show me someone who doesn’t. This one though, so far from the familiar and perceived as it was through the haze of illness, felt like some strange new kind of hell. The old fashioned, 1950’s style wood skirting and tile design did nothing to reassure one who is accustomed to the clinical sterility of western healthcare. In my state of compromised clarity, I managed to communicate to my student, Gurudev, that I was in urgent need of a toilet and he swiftly assisted me to navigate through the dull-eyed throng of waiting patients and find one. I wasn’t expecting to be challenged though, by the sudden appearance of a member of the nursing staff who insisted I remove my trainers before going in. Apparently I wasn’t expected to be barefoot despite this, as it was considered acceptable for me to wear my student’s flip-flops. As these had been soiled by the same streets as my own trainers, I remain at a loss to explain this logic. Apparently my student also found it hilariously confusing. Thankfully we negotiated the random requirement before my system gave way yet again to another bout of self-purging and I returned gratefully to collapse on the bed that had been found for me (rather more swiftly than if I had been Indian, I imagine). In a combined attempt to distract myself, ease the boredom of my chaperones and genuinely learn more about my adopted culture, I enquired to my student as to the significance of an image on the wall of an elephant deity depicted in leaves. This didn’t get me too far though as he seemed oblivious to the details too, simply conceding that some people had all kinds of strange superstitious beliefs. This brought us on to a conversation about the morality of ridiculing other religions. Apparently Hindus and Muslims are engaged in an ancient and ongoing holy war of comic belittling of the ‘My God’s better than your God’ style, while Sikhs take the mickey out of both but people tend to leave the Buddhists alone because there isn’t much to make fun out of in logic.

If you’ve been regularly following my blog, you’ll recall that though generally, my health has been good; I’ve been enjoying the cuisine (spicy food does not upset my system) and doing my best to stay physically fit and healthy (I joined and have been using a local gym as well as maintaining some yoga practice), I’ve not had a completely spotless medical record. In November, I had what appeared to be my first bout of food poisoning. This was embarrassing but no worse; it’s perfectly possible to eat something dodgy in the UK, in fact I distinctly recall a particularly evil houmous sandwich that once knocked me out for over 24 hours. Then, on our way back from Bihali, I was flummoxed by what was apparently my first ever experience of car sickness. We decided this was probably a combination of fatigue, altitude, a full day in the car on winding roads and too much lunch. Whatever. Such is life. I recovered.

I didn’t recount the details in the recent update on our trip to Raipur, because I didn’t want to undermine the important facts about the visit; namely the students, but actually that had been a pretty wretched experience for Mark and I. Mark felt ill before we left, and became sick as we arrived in Raipur, so, when I was hit for a third time, it seemed irritating but inevitable. I must have caught the same bug or virus. It took me a little longer to get over that one, but I flopped back, even if ‘bounced’ back would be a little exaggerated. By the time the following weekend rolled round, I was feeling 100% and rather perky. I was bouncy for enthusiastic participation in the New Year party and the inauguration celebrations the next day. After the ceremony, I energetically delivered a presentation for our students on my experiences and learning at the NNBY convention. I had an important message to communicate and seemed to achieve this well.

Quite literally the minute I finished delivering this, as I packed away the projector and laptop, I was overcome with a wave of nausea and fatigue. I had to sit down to finish putting the equipment away but I got out my notebook and dutifully attempted to participate in our scheduled teachers meeting, to plan the content of the coming week. Feeling faint, I had to lie down instead. About ten minutes later, once again, I said goodbye to what had been a lovely lunch as I succumbed to sickness for a fourth time. Now, those who know me well will know I tend to the self-medicating. If a bit of me has not actually dropped off, I do not like to trouble myself or medical staff with my ailments. This is especially true when I am very far from any familiar healthcare providers and am not actually sure exactly how to go about accessing it. As I stared up at the spinning ceiling; however, I couldn’t help wondering if there might be something a little more to an inconvenient but apparently unrelated string of maladies. Perhaps, I thought, it was time to seek some medical advice.

Later that day, after I’d rested enough to feel like could walk, Mark and one of our more confident, English fluent students, gave up their evening, to my eternal gratitude, and came to help me find a doctor. The first place we visited, the Dr Ambedkar hospital, was closed. The rickshaw driver who had taken us then suggest and dropped us at a different clinic, which had no doctor available for another 90 minutes. Mark thought he knew where there was another place as he’d seen people queueing, so we trudged round the corner. Lo and behold, third time lucky and we were shown into an examination room to wait.

Now, I hate hospitals at the best of times, show me someone who doesn’t. This one though, so far from the familiar and perceived as it was through the haze of illness, felt like some strange new kind of hell. The old fashioned, 1950’s style wood skirting and tile design did nothing to reassure one who is accustomed to the clinical sterility of western healthcare. In my state of compromised clarity, I managed to communicate to my student, Gurudev, that I was in urgent need of a toilet and he swiftly assisted me to navigate through the dull-eyed throng of waiting patients and find one. I wasn’t expecting to be challenged though, by the sudden appearance of a member of the nursing staff who insisted I remove my trainers before going in. Apparently I wasn’t expected to be barefoot despite this, as it was considered acceptable for me to wear my student’s flip-flops. As these had been soiled by the same streets as my own trainers, I remain at a loss to explain this logic. Apparently my student also found it hilariously confusing. Thankfully we negotiated the random requirement before my system gave way yet again to another bout of self-purging and I returned gratefully to collapse on the bed that had been found for me (rather more swiftly than if I had been Indian, I imagine). In a combined attempt to distract myself, ease the boredom of my chaperones and genuinely learn more about my adopted culture, I enquired to my student as to the significance of an image on the wall of an elephant deity depicted in leaves. This didn’t get me too far though as he seemed oblivious to the details too, simply conceding that some people had all kinds of strange superstitious beliefs. This brought us on to a conversation about the morality of ridiculing other religions. Apparently Hindus and Muslims are engaged in an ancient and ongoing holy war of comic belittling of the ‘My God’s better than your God’ style, while Sikhs take the mickey out of both but people tend to leave the Buddhists alone because there isn’t much to make fun out of in logic.

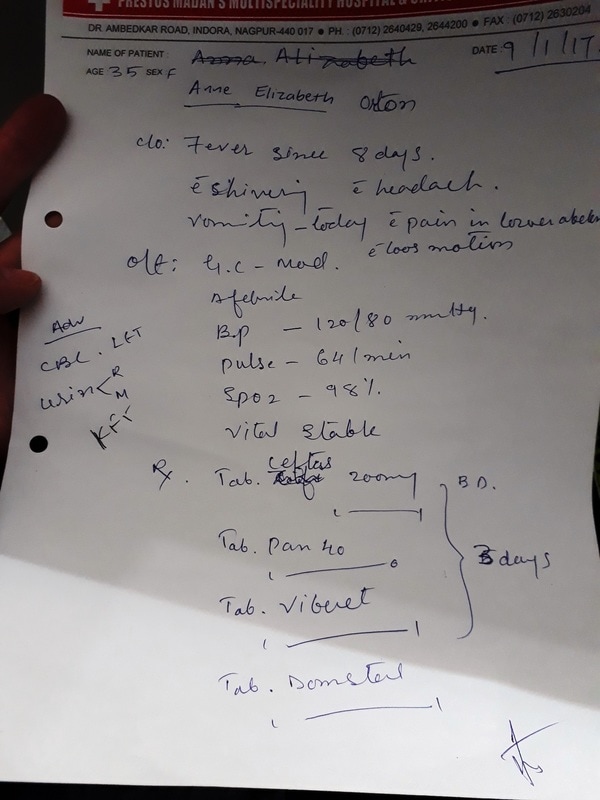

| We were soon joined by three medical staff and again, I wondered how common this might be or if such attention was merely caused by the arrival of an apparently exotic specimen. I was presented with an old fashioned glass thermometer to clamp under my tongue and I obediently obliged whilst trying not to think about where else it might have been. The most senior practitioner examined me vaguely whilst asking questions and making decisive statements to her colleagues with regards to a likely diagnosis. Kneading my tender abdomen as if I were to become the evening chapatti batch, she quickly concluded that I had a water infection based only upon how much I winced when pressure was applied to certain areas, an assumption that seemed way off the mark to me as it did not seem to be suggested by my symptoms. Even she seemed surprised when I replied that no, I’d not had any difficulties passing water but she remained adamant declaring; ‘Water infection and gastric bacteria!’ (or something similar) with the air of one who has just solved the last, niggling clue of the daily crossword. She scribbled a few personal notes (Mark helped with an approximate spelling of my name) and left after demanding a blood test. |

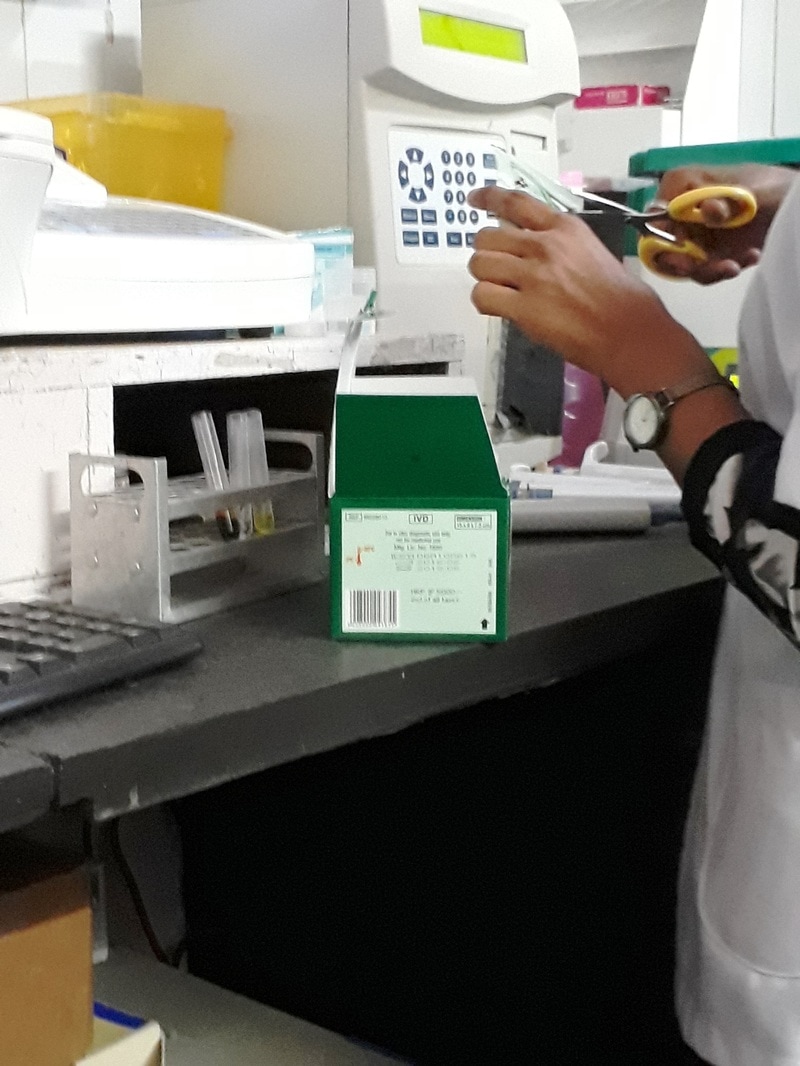

I was shortly shepherded into a new room where a gentleman sat at a computer and a lady busied herself with an array of various pieces of analytical equipment, bloody bits of cotton wool swab scattered at her feet, having missed their target of a simple waste paper basket. So much for careful disposal of clinical waste. As she advanced towards my arm with the needle,

| I recalled that at a recent visit to the blood donation centre in Manchester, just before leaving for India, the nurse had struggled to find a vein in my left arm before collapsing the one she did find, bruising me and finally admitting defeat before calling a colleague to take over, who then started on the other arm. With this in mind, I politely communicated that she might like to try the right, wondering how much I would be punctured before the required quantity was obtained. I needn’t have worried; despite the questionable surroundings, she was clearly well practiced and skilful, drawing the sample she needed quickly and without fuss. Manchester Blood Bank staff – 0. Indian Phlebotomist – 1. I was amused by the different responses from my escorts; Mark wasn’t sure at all and said he didn’t want to look while Gurudev leaned over eagerly to get a good view. I was rather glad. It’s always easier to feel genuinely brave when you’ve got an audience to convince. While the nurse busied herself with analysis (I was absolutely fascinated by this, it seemed like a much better system than having to wait days for it to be returned from a distant laboratory), I was handed a familiar looking plastic tub and asked to provide a urine sample. A small, wiry lady in a simple but colourful sari was called and she led me with a vice like grip that seemed only a hairs depth from bruising my arm, to an outdoor squat toilet, screened from the main waiting room by only a waist height brick wall. She further tightened her clutch and indicated for me to get on and fill my pot. Well. There are a great many cultural differences that I’m willing to experiment with. I’m learning not to depend on toilet paper. I can generally finish a meal without cutlery, even if it does include watery Maharashtrian dhal. I can wearily remember to remove my shoes when required, despite the fact that this seems to make my feet even dirtier than if I’d kept them on. There are things I draw the line at; however and I’m afraid I have not yet let go of the English conditioning that means I do not urinate whilst being watched by strangers. Maybe, if I’m desperate and it’s been a long night, I’ll accept the presence of a close female friend but that’s my limit. Cue my reliance on Gurudev once again, who was called to explain that yes, I really was able to get on with it alone and wouldn’t fall over without her support. She didn’t seem to quite follow though, and stepped back with some confusion to watch, and wait for me to get on with it anyway. Eventually she was persuaded that I could also make my own way back to the clinic, thank you and good bye. Sample in hand, I returned to the office-cum-laboratory and we waited a little longer. I was then given a printed analysis of my blood sample, which I was responsible for ferrying back to the doctor. I found this both fascinating and refreshing, it seemed like such a quick and simple system. I also enjoyed a good nosey and deduced that with a white blood cell count higher than the given normal range, my immune system had kicked in and my body was indeed fighting off some sort of infection. I felt somewhat vindicated; there was a reason I felt so ropey! I was directed to leave my little tub of wee on the windowsill for some reason and we were dismissed. |

Shortly after that, we were ushered into a different consultation room, containing a remarkably expansive desk about three times bigger than the examination bed in the corner. Funnily enough, I relaxed a bit when I spotted a portrait of Dr Ambedkar on a shelf next to a small Buddha rupa. Perhaps it was just a little familiarity, perhaps it was a sense that the person who used this office was one of ‘my’ people but either way, it was a noticeable response in myself. We then observed a small room off to one side, almost like a little antechamber, that housed a variety of religious icons in a sort of multi-purpose shrine room. I know UK hospitals often have chaplains and prayer rooms hidden away somewhere but I’ve never seen or used one. I suppose this is simply another example of religion being so much closer to the surface of Indian culture. There were two other patients in this room who were being treated by a man behind the desk, a stethoscope casually slung across his shoulders as I imagine an actor might wear one in an American sitcom, just to be clear that he’s the doctor. We were invited to sit, while they continued discussing what I imagine were personal medical details without even batting an eyelid with regards to our presence. There were also several other members of the medical team in the room, who I got the impression were kept close at hand to provide not so much assistance, as an audience to this man whom, whilst I am sure was very well meaning, had possibly the biggest ego I have ever had the opportunity to encounter. The other patients eventually left and he turned his attention to me. After a string of apparently unrelated questions that I took to be simply nosy curiosity or an attempt to practise English, he decided the time had come to use his prop. I’m not quite sure how effective a stethoscope is when used over several layers of clothing and left in position for less than a second in each random location to which it is applied, but he seemed satisfied and I wasn’t about to volunteer any exposure of flesh. At this point, he spotted the top of the tattoo I have running down the middle of my back. ‘What’s this?’ he demanded suddenly. It took me a while to work out what he was referring to but I eventually realised and explained that it was Mercury; the nearest planet to the sun and the start of the diagram of the solar system tattoo that runs down my spine. After telling me that actually, I was wrong, that wasn’t the solar system because there was no Sun (!?), I was directed to the bed, where my abdomen received another pummelling. When he was satisfied, I was allowed to sit back up to be informed that it was a great thing to have the planets on my back as I was channelling their energies into my spinal chakras and drawing down great blessings from the gods. All good there then. After a regal glance at my printed results, we were instructed to go and collect the results from the urine sample. We were treated to some more theatrics upon our return and I was informed (and pleased to know) that I did not have malaria or dengue but had in fact contracted two separate infections, one of the gastric system and one of the bladder. Some scribbled prescriptions were made on my notes before the first doctor who examined me was hailed to the throne room and made to stand in front of the desk like a troublesome student before the headmaster. She was then subjected to the most undermining demonstration of arrogant criticism I’ve ever had the misfortune to witness as the doctor listed all the things she had not done properly in her treatment of me as a foreigner. I managed to hold back a physical wince but couldn’t quite stop myself from commenting as I interrupted to inform him in no uncertain terms that I had been very happy with the care I had received from her and was impressed by the nature of her bedside manner. I’ll confess, this was something of an exaggeration but I felt impressed at least that she’d accurately diagnosed a urinary tract infection with no more than a few prods and I felt the need to somehow redress the imbalance of his unfounded tirade. My comments were deflected from the force field of the super-ego with the same disdainful wrist-flick with which this poor, and one imagines long-suffering, woman was dismissed.

| I was finally handed my notes, a prescription on the back page, and told to eat well, take rest and return the day after tomorrow. I exited with a respectful ‘Jai Bhim’ but this was not reciprocated and I was simply met with a blank stare as I was told ‘good bye’, which made me internally question the presence of the portrait of Ambedkar behind the desk. After settling my bill; 2800 rupees in total, we gratefully filed out into what passes for fresh air in Nagpur, to find the chemist. Though we’d ended up using a facility at the higher end of the healthcare costs spectrum, I reflected simultaneously how cheap it actually was (that’s around £30) and how lucky we are in the UK to have a system where the quality of your care, and indeed whether you get any at all, is not directly dictated by your financial security. I then collected an unholy quantity of mostly unlabelled drugs, plucked from random packets with no dosage instructions, or other information from a pharmacist who seemed completely baffled by my repeated requests for more information. We filed back to the hospital and managed to get some details on how and when to take them even, if I was none the clearer on what many of them actually were. I was grateful to be collected from the city centre by Aryaketu then, and driven home to reluctantly consume some weak soup and toast in order to buffer the first dose of mystery medicine. Thankfully, after another week or so of being very gentle with myself and one return visit at which I was prescribed another two weeks of chemical antibiotic cocktail, I am now feeling probably at my healthiest since that first bout of food poisoning knocked me for six back in November. My theory is that a strong immune system was able to deal with this initial shock and suppress but not completely irradiate the new pathogen, which then put up enough of a consistent challenge to a body gradually becoming more run down by changes in diet and environmental conditions to result in an increasing frequency of symptoms that then took ever longer to regain some control over. So in summary, I can’t say the whole ordeal was a pleasant process, but I’m now very glad I went and can enjoy both the novelty of feeling genuinely healthy again as well as the reflection of yet another unique experience afforded me by my time in this country of constant discovery! Anyone wondering, like I, about the sterility of the thermometer, need not fear. Upon peering more closely at two jars of bright orange liquid housed on the reception desk next to a leaning pile of paperwork, I discovered that they are sterilised (one assumes between each patient) in their own separate jars labelled ‘oral’ and ‘rectal’. No room for errors there then. I feel completely comfortable with that. Ahem. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed