Apart from the very obvious reason that I was keen to recover as quickly as possible from my newly diagnosed infections for reasons of personal comfort (as discussed in my recent tales of dukkha from the hospital), there was another factor. I had an event coming up in the diary which I was totally unwilling to miss, come hell or high water. At the end of December, I was fortunate to attend the National Network of Buddhist Youth 10th National Convention; the most eye opening week of my time in India so far. I had quickly realised that though I’d found the experience richly rewarding and intensely useful, I was entirely the wrong beneficiary and so had begun what proved to be an at times challenging process of organisation to take as many of our Aryaloka community students as possible to an upcoming NNBY Regional Conference, this time in Bihali, where I’d enjoyed a retreat only a few weeks ago.

Of course, I’d have liked to take all our students but I knew from the outset that this wouldn’t be possible. There were too many factors prohibiting it. Retreat fees and travel were the first and foremost obstacles, with additional uncertainty around exam dates, supervision and duty of care. Fortunately, I had the support of Diksha, one of the main organising team, whom I had got to know in Bordharan as the facilitator of my discussion group and she was very keen to help with arranging some of the travel. I’d also snuck in an informal conversation about the possibility over lunch on the final day of the National Convention with two other key people; retreat leader Maitriveer Nagarjuna and Aryaloka Director, Aryaketu. All these interactions had felt very constructive and my enthusiasm for the idea was received positively by the rest of the Aryaloka team when we returned to Nagpur. Unfortunately, when the reality of organisation kicked in and the prospect became elevated beyond the status of ‘nice idea’, it became far less straight forward and there were a couple of really quite difficult moments when it seemed I was simply not going to be allowed to take any students at all. I knew that at the very least I could still attend; I had promised to deliver a fuller version of the rather impromptu talk I gave in Bordheran, as well as running a workshop or ‘floating session’. As long as I could get myself by bus to Amravati, about half way between Bihali and Nagpur, Diksha had promised to organise a car to collect me.

| Going alone would have been better than nothing and I knew some young people could still benefit from my contribution, but I also knew how valuable our students would find it and was absolutely determined not to back down. Still, not to dwell on adversity, it’s enough to say that thankfully, it was eventually possible to navigate the challenges and find solutions to the very valid concerns presented by my colleagues. It was agreed that two students, one representative from the young men’s and one from the young women’s communities, would accompany me with the responsibility of reporting back to their peers on the experience. I’d already delivered a presentation to both groups about my time at the National Convention but better by far for young Indians to hear about the work of NNBY from other young Indians, not a rapidly aging English lady. I had to concede, that though this wasn’t half as many students as I’d thought we could take (I’d decided I could afford to pay retreat fees for up to six) it did solve some problems with regards to travel and would be significantly less stressful than being personally responsible for quite that many! It made the whole thing a little cheaper too and I could then afford to pay their travel costs as well, which ended up being no more than contributions to petrol as we’d received the very kind offer of a lift all the way from Nagpur to Bihali from Chetan, a main NNBY organiser and very committed youth worker. Aryaketu chose who should attend based on considerations such as academic progress and exam dates so there should be no worries around apparent favouritism (which had been a concern) and we would even have a spare seat for Mark, who was keen to come to find out more about NNBY and offer a workshop on Climate Change, one of his key passions outside of English teaching! Needless to say, after all that, there was no way I was going to be too unwell to go. Fortunately, I was indeed feeling genuinely better, with energy levels once again approaching normality by the time a rather excited car full departed Nagpur just after lunch on January the 19th! |

I am equally delighted to report that the trip was very fruitful for all of us. Once again, I got a lot personally from attending, as I know did Mark. I could tell from their enthusiastic participation (it demonstrates a particular kind of commitment for a teenager to be out of bed and ready for pre-meditation Chi-Kung at 06:30) as well as the little bit of English conversation we could manage, that students Bharti and Akhilesh had also gained much. It wasn’t until we were back in Nagpur and working together to prepare their presentations that I realised quite how much; however. I’m only slightly embarrassed to admit that when I heard the depth of their experience for the first time in translation, I was almost moved to tears. I’ll let their feelings have their own space in a moment, for they are the most important words I’ll include in this piece, but I shall just share a couple of my own most significant experiences first.

| My main aim for our mission was for Bharti and Akhilesh to have meaningful experiences that fully demonstrated the potential benefit of their future involvement in NNBY, and that they felt able to communicate this to the others upon returning to Nagpur, but I did of course have some other focuses as well. In Bordharan I had planned (at the last minute, but planned none the less) to give a version of the ‘Why I am a Buddhist’ talk that I delivered at Vajrasana in September. This had ended up being condensed on the spot (you can actually find a video of it here) into only about 7 minutes (including interpretation), so I was very happy to have the opportunity to give a fuller version in Bihali as I’d spent quite some time thinking about the content and how to make it relevant to a new audience. Hearing from others on their experience with the Dharma is always useful but still, there would be very different things to say to make it relevant to a group of Indian Youth in the Maharashtrian Jungle as opposed to a group of Europeans at a rather civilised Beginners Retreat in Suffolk. I knew they’d be keen to hear something of an autobiography; you don’t get far at a gathering of Indian youth without multiple questions about your origins, I have discovered! I felt there was something more important than that though and I wanted to explain why I was there. I’d been instinctively aware, as well as confirming from some conversation at Bordharan, that the reason for my attendance could be easily misconstrued and reduced to mere tourism. I felt a strong need to demonstrate that this wasn’t the case. I also wanted to explain why my Buddhist practice was so important to me in the hope that it might help support that of others. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I felt it was really critical to demonstrate commonality. I can only guess what assumptions a mind from an Indian cultural background is conditioned to make about individuals from the West but I know that at least some of them are completely unfounded and really quite damaging to genuine racial cohesion. My approach to these areas in my talk was mostly couched in spiritual terms but there was a key socio-political link too, with reference to the work of Dr Ambedkar and why it might be that a 35 year old Brit can find his words as inspiring as an 18 year old Indian. My basic point was that though we come from very different backgrounds (as demonstrated by the autobiographical introduction), we are certainly following the same path into the future as we work for a common goal of global unity as described by the Buddhist teachings presented by Babasaheb Ambedkar. Some of the questions I’ve had since do make me wonder how much of what I said was lost in translation, as I’m sure I covered some of the answers to those in the talk itself. I tend to use quite subtle turns of phrase and rely heavily on analogy to communicate some of my more creative ideas so I just can’t tell how well much of that came across, but still I must have been doing something right to sustain the apparently rapt attention of the group for over an hour. I didn’t feel it flowed quite as well as my original talk but I think this is as much down to the practice of speaking with an interpreter as anything else. Hopefully this is a skill I can develop. I feel confident I got the gist of what I wanted to share across, anyway. |

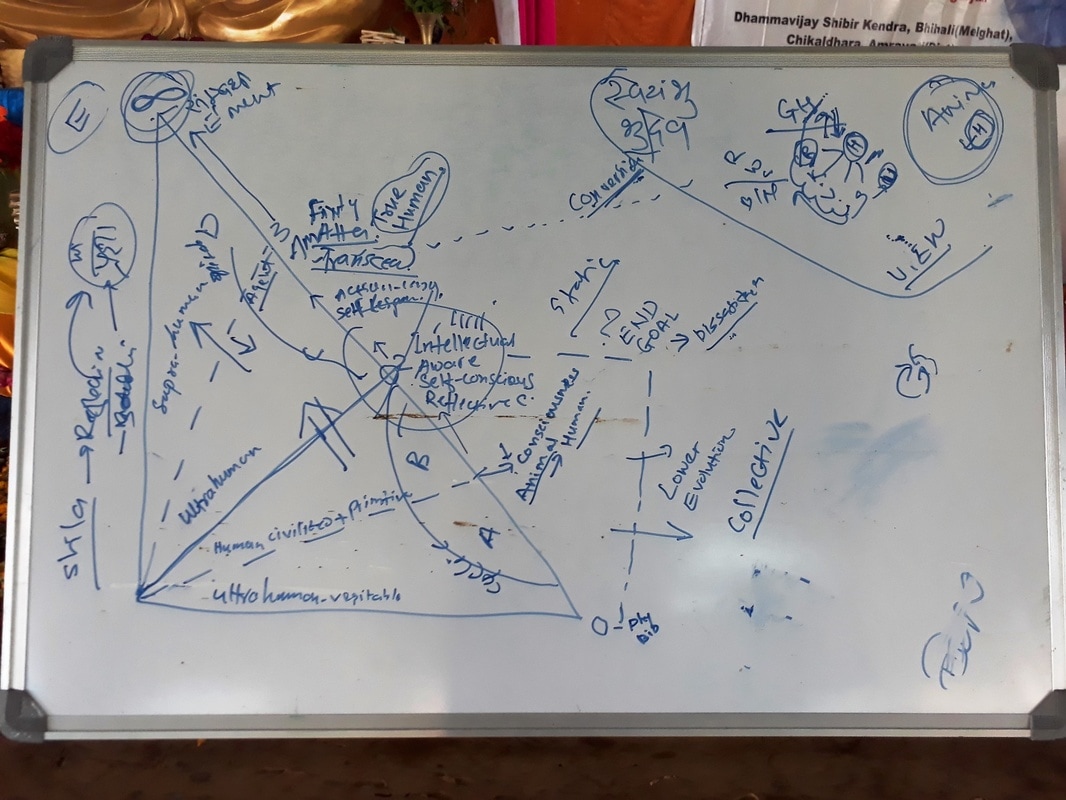

| On the second day, I delivered a creative workshop aiming to use visual communication to stimulate a discussion of the things that feature prominently in the lives of the participants and could be seen as formative elements in the concept of self. The purpose of this was to help people establish where they are currently at in their life, with the view to identifying opportunities for positive change and development, particularly in the very Buddhist terms of a non-fixed self. We know we can change, we know we will change, but how can we realise the sense of deliberate focus that we need to achieve this in the most positive way? I’d planned to use an almost diagrammatic form to deliver this and had pre-prepared some blank mandala-style pages for participants to draw on. Though I’ve plenty of experience delivering various arts workshops, I’d devised this one specifically for the convention and had never run it before so I was grateful to Maitriveer who made time to go over it with me before I started and ask me a couple of pointed questions that helped me refocus my objective. I was fairly confident but still felt relieved that it was well received and everyone who came along seemed genuinely pleased with their outcomes. |

| At the same time that I was delivering this, Mark ran his workshop on Climate Change. I was very glad of his presence and support at the weekend on level of simple friendship, but I was particularly pleased for practical reasons that there was an alternative provision for participants and so I didn’t have to try and contend with fifty in my session! Chetan also ran a seminar on a personal development technique called SWOT Analysis. I can’t pretend I’d ever heard of it but Akhilesh found it very useful! | |

Beyond the obvious work involved in preparation and delivery of appropriate content, there is perhaps a more important role fulfilled by leaders and facilitators involved in any kind of youth work, which is much harder to pin down or qualify. This role is simply to be present, to be engaged, to listen and to demonstrate a deep degree of care. I knew that being available (energy levels permitting) during meal times and rest periods to engage with people informally was important, but there was one particular conversation that gave me a really startling insight into my adopted culture which will stay with me for a very long time. One young woman had asked to speak with me for some advice on how to practice English, having moved back to her home village after some time away studying. As she was no longer spending time with people who valued the use of English, she was finding it difficult to keep it up and felt her command of the language was suffering. I suggested a few things; reading books and newspapers, accessing English films and talks on the internet where possible, offering to teach the language to her local friends who dismissed the importance of learning. She seemed to receive these suggestions well and I was satisfied I’d helped as much as I could, yet she had one further question.

| ‘Why,’ she wanted to know, ‘do the organisers call you by your name when they introduce you?’ I was completely baffled by this question and felt sure I’d misunderstood. What else should they call me? After some further discussion it became clear that she was asking why they had not used a formal term of respect when inviting me to speak. I was pleased to have the opportunity to explain that it was because we were following the key Buddhist principle of equality that Babasaheb himself had been so active to promote. After receiving a mildly blank look I went further to state ‘because I am not better than them. I am not better than you.’ I may as well have stated that grass grew in the sky and we had clouds gathering under our feet. ‘Yes you are!’ was her instinctive and wholehearted reply. As I come to write this I find an uncharacteristic inability to articulate quite how that made me feel and realise that such was the importance of the exchange, I still feel quite emotional about it even now. It cut absolutely right to the heart of me that this sparklingly bright human being, simply bursting with manifest talent and clear potential, had been so conditioned by her upbringing in a society of deeply entrenched hierarchy that it was completely beyond her perspective of the world to believe that I was anything other than some kind of superior being. As a teenager, I certainly respected my teachers and those I met in mentoring or leadership roles. I understood that they’d had more experience than me, that they’d had more years of learning and education, that their thoughts and statements were the culmination of their deliberate efforts and that careful consideration was due. I wanted to listen and to learn from them. I wanted to demonstrate my appreciation of the time and teaching that they gave me and I even hoped to follow the example of one or two of them in my own life; but I never, for one moment, supposed that they were better than me. More skilled than me at certain things, yes, more practiced than me in many areas, of course, but not quantifiably better. Suddenly, I felt a little window had been opened for me into the world of caste discrimination and I realised just how much work we have to do. It’s not enough to say we believe in equality. It’s not enough to say we reject parts of a religion that attributes fixed and unchanging birth privilege to divine whim. It’s not even enough to renounce the entire religion that preaches this and convert to a new one if the bedrock of our cultural experience, the foundation for all our interactions and the way we place ourselves and others in the world is formed from the sediment of oppression and erroneous discrimination that has accumulated over centuries. Legislation is not enough. It’s not even a start. It’s simply a signpost, a practical suggestion for a direction to move in but nothing like the change in attitude, the change in minds that will make a real difference. How, then, can we possibly break through such barriers and why does it matter? What difference does it make to my life, when I return to the UK in a few weeks, or to the lives of my English friends who have perhaps never even left the UK? Why should it trouble them if a community on the other side of the planet is living in such conditions of social inequality? We can donate money to feed people. Even better, we can donate money to educate them and empower them to feed themselves, but if they choose to follow a dogma of division what is it to us? Compassion isn’t just about financial poverty though, and anyway what good are these employability skills really, if you can’t utilise them because you’ve not got the social liberty to follow certain careers without prejudice, even if the legal framework theoretically supports you? Still these issues are closer to home than the cultivation of philanthropy from a distance. If we want to be equal, if we want to live and operate in harmony and with the respect due to us from other humans, then we need them to know, to see and to feel that they too are our equals. Different, yes, and delightfully so, but always free and above all, equal. If I want to be truly valued as an individual with my own unique skills and talents that I have invested time in developing, then the last thing I want is for someone to elevate me to a pseudo superior status based upon factors beyond my control such as age and skin colour. This does not afford me any more equality than it affords her, and that, after all, is what equality means. Without wanting to get too Orwellian, if some are more equal than others then no one is equal at all. This is a contradiction in terms. It is quite simply then that if you wish equality for yourself, you need it for others. And it’s not enough to stop at the boundaries of your town, your county, your country or your continent. The world is bigger than that and so, I believe, is our potential as members of the only kind of society that can possibly support any kind of human progress. I hope I managed to communicate to this young woman that the only difference between us was based purely in our life experiences. I hope I managed to make my point that I’d simply benefitted from a few more years’ to learn from my many mistakes and had been born, randomly, in a different set of circumstances. Even if she didn’t get quite the same clarity of insight as I did then I at least hope I planted a seed. The conversation certainly got me thinking along new lines and I began to consider how appropriate it is for the students at Aryaloka to address me as ‘ma’am’. Is this apparently harmless pleasantry actually reinforcing the very hierarchical systems we are trying to demolish? Should I encourage them to stop saying it? From this I mused; why erode respect? Perhaps it’s better, rather than removing such terms, to demonstrate mutual respect by reciprocating. I don’t always remember but I’m trying to do so now when addressing the students I work with. Of course, following this, there was an obvious person who sprung to mind when wondering who to ask for help with translating the audio recordings of Bharti and Akhilesh’s presentations and I have to say she’s done a great job, responding both enthusiastically and promptly. I only hope she’s benefited as much from the English practice as I have from learning the content of the talks and it is in part thanks to her that I’m able to carry on into the most important section of my writing with such detail on my students’ responses to the convention. Vishakha ma’am, thank you. I hope this paragraph provides you with yet more English practice and let it be known that I am not only no better than you but have in fact learned a great deal from you. Just like many of the young people I have had the fortune to meet since I came to India, I am quite confident that you will do very well indeed. |

Although I’d picked up a clear sense that Bharti and Akhilesh were enjoying the convention, it wasn’t until the day after we returned that I felt some certainty that they had benefitted from more than just the novel excitement of a weekend out of Nagpur. Having asked them to deliver presentations about it, I knew they’d need some support in putting their thoughts together, so the four of us met on Monday morning, with the help of Joydeep, a men’s community member, whose English was already excellent before he started the course, to the degree that he’s often called upon to translate Shakyajata’s Saturday Dhamma classes. I’d had the idea that it might be good to run the two hour afternoon presentation session like a day on an NNBY convention and I was glad that everyone readily agreed. We planned to start with a mini Chi-Kung session (led by Bharti), then

| a short meditation (lead by Akhilesh). We’d then move on to their main presentations before splitting into discussion groups and reconvening for a Q&A session, where groups could put any questions they had to the pair. We’d finish with a puja. That was all fairly straight forward but of course the hard work was still to do; we still had to write the presentations! I suggested using PowerPoint to help them keep track of what they wanted to say and as a method of displaying some of the many photos that they’d both enjoyed taking, either on Mark’s mobile camera or my SLR. Easy enough and good practice in using those programmes too. This only left the content to decide upon! I knew they’d been taking notes over the weekend (I’d bought them each a brand new notebook to encourage it!) but that’s a long way from having a prepared presentation, and my experience of working with young people is that they need a significant amount of help in recognising the most important things to say. This can be a challenge in itself but it’s even tougher with a language barrier. Sure enough, to begin with, they needed a little prompting but I could tell even without Hindi that Joydeep was himself doing a very good job of coaxing out the key points without interference from me. I listened to him interpret Bharti’s account of how she’d found the conditions very supportive to deepening her meditation practice and how she’d enjoyed learning a new approach to the Metta Bhavana. I listened to him explain that she felt she’d learned a lot more about the teachings of Babasaheb, about why he’d taught his people to follow Buddhism, about the significance of questioning the superstitious spiritual practices that she’d been so used to at home. I heard her thoughts on gender roles and how she now realised she had the same potential to achieve excellence as anyone else, that she believed girls should be encouraged to go on retreat to develop confidence and gain clarity around their identities. I heard her state quite deliberately and without any prompting, that she wanted to maintain her involvement in NNBY to support her own continued development and to take friends so they too could benefit as well as to challenge to the restrictions on travelling away from home that are currently placed on girls in many villages. I felt a lump rise in my throat as the reality sunk in to my mind that the combined efforts of all my friends and colleagues who’d gone out of their way to indulge my stubborn insistence that we should attend had not just been ‘worth it’. Those efforts had been our absolute obligation as teachers, as mentors and as dharma practitioners. Akhilesh recounted a similarly positive experience and explained that attending the convention had clarified a lot of his previous confusion around the purpose of following a Buddhist practice. He felt that the main benefit he’d gained was in seeing equality exemplified. He’s not from Maharashtra and was concerned that he would encounter coldness or discrimination from the regional participants but recognised that this had been very far from his experience, which, he told us was the first time in his life he’d realised such genuine equality could exist. He’d in fact felt so included that at times he’d had to take himself away from the group in order to make time to write his notes! He too had a clear idea of what he planned to discuss in the presentation and hoped to give his own perspectives on the main talk given by Maitreveer Nagarjuna on human evolution and how this related to social, political and spiritual factors. For the second time in one update, I find I’m at a bit of a loss for words to describe quite how I felt upon hearing all this. Proud, certainly, and delighted that they’d both responded so hungrily to an opportunity that hadn’t been smooth to arrange. Joyful, definitely, to see how fired up and motivated they both were, how eager to share their experiences that others might benefit. Most of all, the best word to describe how I felt is moved. Moved in the emotional sense, as the reality of the real difference we’d made to their lives came home to me but also moved in a dynamic sense and ever more determined to drive forward in whatever way I can to keep supporting these young people in their developmental leaps and bounds. |

| | It’s very rare to be able to say that anything in India has gone to plan, in fact I’ve come to see plans as a rough guide that give me an idea of what is probably not going to happen, but it’s entirely to the credit of Bharti and Akhilesh’s enthusiasm that the presentation afternoon went like a dream. There were unplanned factors, of course, including the arrival and subsequent attendance of Aryaloka’s main benefactors, the additional pressure of whose sudden presence gave even me an unexpected dose of performance anxiety. Bharti and Akhilesh; however, more than rose to the occasion and appeared to actually relish the additional audience members. We’d decided that it would be good practice for them to write their PowerPoint presentations in English and deliver the introductory sentences in the same, but that to foster a genuine degree of communication, they could give the main talk and answer questions in Hindi. As such, although I had a rough idea of what they were discussing, most of it went right over my head. In my formal teaching history, this would have caused me some anxiety as I would worry that I’d not be able to support and direct the content if needed. How would I know they were on topic? How would I know they weren’t accidentally misleading their peers with confused interpretations of complex concepts? How would I know they weren’t just chatting about what they fancied getting up to at the weekend? Actually though, I found their confidence gave me some structure to relax against and when I opened up to trusting them with the job of communicating their own thoughts, I found that not being overly focused on the language gave me some space to notice other key indicators that all was well. Aside from the occasional words I did recognise to show we were on track (‘NNBY’, ‘Dhamma’, ‘Babasaheb’ for example), I could gauge from the engaged body language of both speakers and audience, as well as from the enthusiastic pace of the discussion, that there was a good deal of focused and genuine communication taking place. Group discussions can be tough to get going and Question and Answer sessions flat and dead in the water with even experienced adult participants but there were no awkward silences or confused pauses, in fact we had a queue of people wanting to ask their questions first. Again, with thanks to Vishakha for her translation of the transcripts, I can now tell I was right not to be overly meddlesome in the flow of interactions and it seems the content was a mature and respectful debate that would put most Question Time |

panel members to shame for it’s degree of mutual respect and open minded inquiry. My favourite part of the dialogue (translated by Vishakha and with additional clarification and grammatical tweaking from me) is as follows:

Q: After the convention what changes will you make in your society?

A: (Akhilesh) I will try. Actually, before, I used think about how my mother and all the members in my family worship Gods and Goddesses. I was the only one who was not following this and from start I was confused and somehow I found it wrong. If I argued with my mother about this she used to shout at me but I think by telling her about Dhamma we can change.

Q: How will you change the society?

A: Yeah, it’s possible. (Bharti) First, we have to change our homes, then the rest!

Q: How will you tell your parents about Dhamma?

A: By small, small things. Gradually we will tell them! It's difficult but we can do it! If we build their confidence then we can also do things like that, show our hidden talent and potential by doing a good job and making our parents proud. Believe in ourselves!

Q: If we give these teachings of Buddha and Babasaheb to society and to girls, can we achieve this goal. And excellence?

A: Yes! We should raise our own talents make it more glown! (clapping)

| Actually, I’m not sure what ‘glown’ means. I can’t decide from the context if it should be ‘known’ or ‘glowing’ but either seems quite appropriate and I rather like the idea of a word that means both simultaneously so I shall leave that one open to interpretation. Maybe it means something else entirely. Regardless of possibly vague moments in translation, I think it’s quite apparent from just that brief excerpt that Bharti and Akhilesh did us proud, both in terms of how they responded and participated with the content of the convention itself and in terms of how well they took on the task of sharing their learning and new perspectives so enthusiastically with their communities. Of course, I needn’t have worried too much about what was being said as my Hindi speaking colleagues were also present. Sheetal, Vaishali, Saccadhamma and Aryaketu all attended and were clearly as impressed as I was by the maturity and depth of the presentations. Such was her engagement that Bharti even ended the Q&A session by questioning her peers, asking if they felt they would like to go to an NNBY event in the future. Their replies were an almost unanimous ‘yes!’ So that’s a tale of optimism and positivity for the future of many of the community students at Aryaloka but what of my own responses? |

Well, my motivation is galvanised, my resolve, more focused and my sense of purpose nourished with a deep sense of potential for just how ready many of the young people I’ve met here are to make the most of the support given to them to determine their own development. None of the lazy assumptions I am so used to from the attitudes of many in the UK that a ‘right to education’ is synonymous with not having to apply effort to one’s own progress. But I am aware that there is so much work to do in India, such an important revolution occurring that I feel I must apply my efforts with a degree of discrimination and in a very carefully considered, skilful way to ensure the results of those efforts reach the most lives possible. There are so many projects to work with here, so many communities to visit, so many different states to see. And I feel blinkered. My perspectives of the situation here are so coloured by my own cultural filters that I feel I’m groping around in the dark, not really sure of where to find the best opportunities or how to fulfil the potential inherent in my role when I do. I discussed this briefly with Chetan on the way back to Nagpur, and asked his advice. My experience of India is so limited, my understanding of the complex social dynamics so foetal, my background so different and my appearance so loaded with unknown interpretations. How can I utilise this sense of ‘other’ that I represent to many for the greatest good? There’s no denying that I feel intensely uncomfortable when people appear to bestow respect or privilege upon me for no reason other than my skin colour but how can I best respond to this? Should I try to humbly ignore such attention in the meek hope that I will somehow communicate its fallacy? Or should I step up to my own discomfort and use it to speak the truths that those who afford it to me need so desperately to hear? Of course I need guidance from people with a deeper understanding of the issues but it seems belligerent to deny the opportunity, especially in communicating to girls and women, whose plight is still so much more challenged than many of their male counterparts to a degree we’ve not encountered for decades in Europe.

Practically and in the short term, I hope to run more workshops with NNBY before I leave in March, but in the long term and on a deeper more emotional level, I feel quite certain that the work I have to do in India extends way beyond the expiration of my visa and for the first time since arriving in October I am absolutely adamant that I am coming back. I think there’s something of the small child in my approach to forming attachments. I might take some time assessing, exploring, patiently finding some common ground and establishing a foundation for trust, but once my roots are sunk, I’m a difficult weed to pull up. My experiences of moving around and living in different parts of the UK had already made me question the concept of ‘home’ but now I’m finding the whole notion increasingly irrelevant. One English phrase suggests that home is where your heart is. I’m not so sure about that but I know without a doubt that there is now a big chunk of India, and her people, resident in my heart.

Sorry, India. It looks like this mouse will be a tough one to get rid of...

Practically and in the short term, I hope to run more workshops with NNBY before I leave in March, but in the long term and on a deeper more emotional level, I feel quite certain that the work I have to do in India extends way beyond the expiration of my visa and for the first time since arriving in October I am absolutely adamant that I am coming back. I think there’s something of the small child in my approach to forming attachments. I might take some time assessing, exploring, patiently finding some common ground and establishing a foundation for trust, but once my roots are sunk, I’m a difficult weed to pull up. My experiences of moving around and living in different parts of the UK had already made me question the concept of ‘home’ but now I’m finding the whole notion increasingly irrelevant. One English phrase suggests that home is where your heart is. I’m not so sure about that but I know without a doubt that there is now a big chunk of India, and her people, resident in my heart.

Sorry, India. It looks like this mouse will be a tough one to get rid of...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed