| I’ve been thinking I needed to somehow bring closure, to at least this phase of the Maggamouse Blog for a few weeks now, certainly since I returned to the UK from India, probably a week or two before that even. After all, the dates would have lined up quite nicely if I could have published some kind of departing summary on the day I left. Job done. Case closed. Box ticked. Moving on. Next, please! I decided not to write about my last couple of weeks in Nagpur while still there though. In the few remaining days I had left, it seemed rather wasteful not to spend as many of those hours as possible actually being with eople, rather than in front of a laptop writing about being with them. In theory, there’d have been nothing stopping me from writing this in the days immediately after my arrival in England of course. I could have done it a lot sooner than nearly 5 weeks later. The henna stains on my nails have grown a good half centimetre closer to the clippers since then and the tan line between my toes from my recently spurned flip-flops is barely visible anymore. I’ve distributed all the homecoming presents, I’ve served all the Indian meals I’ve learned to prepare. More than once. I’ve shared the biggest, most obvious titbits of ‘and then this happened!’ or ‘but of course it’s different in India!’, and I’ve almost stopped saying ‘ha’ instead of ‘yes’. The affirmative sideways head wiggle I realised I’d begun to subconsciously mimic, appears to have faded and yesterday, I took the plug socket adaptor out of the bottom of my bag. Later, I might even fish the old Indora to Bhilgaon bus tickets out of my wallet, though if I’m honest, it’s not due to a reluctance to litter that I keep stuffing the Nagpur INOX cinema ticket back in my coat pocket when if falls out with my hanky. An older version of normality is slowly reasserting itself, as if I was uninstalling updates to my operating system, one at a time. Writing about an increasingly distant experience was indeed becoming ever harder to find the motivation for, like a shore line becomes less photogenic as the boat sails on. |

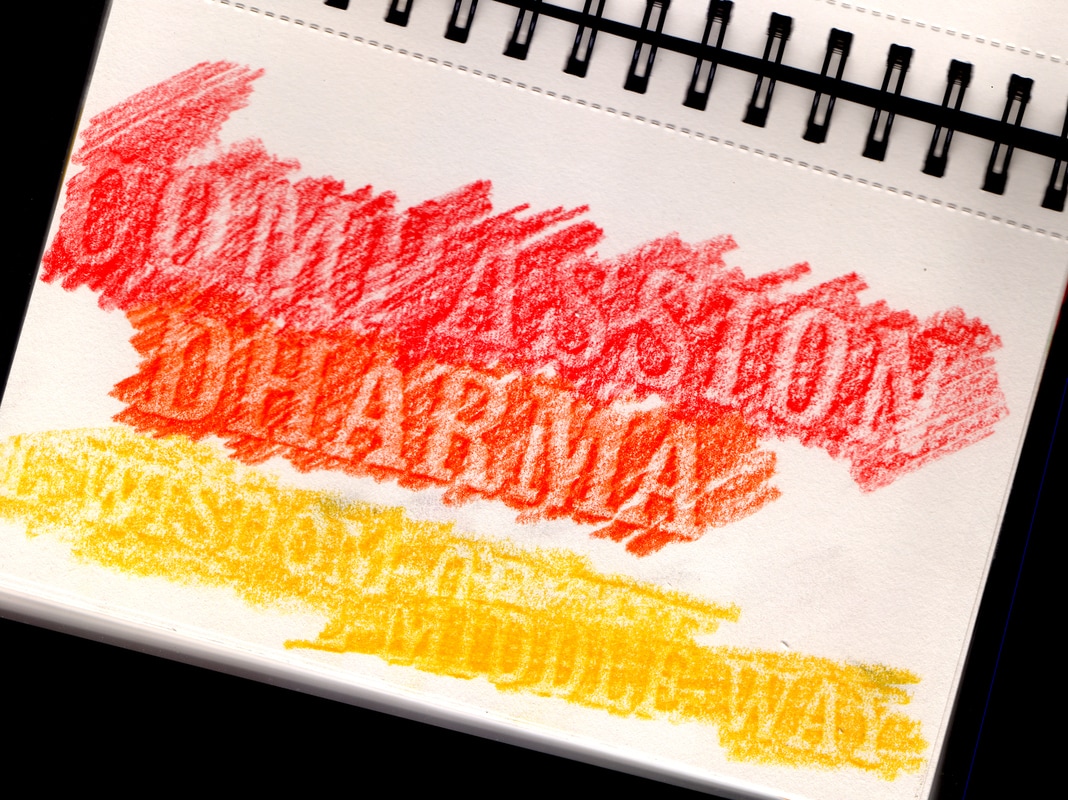

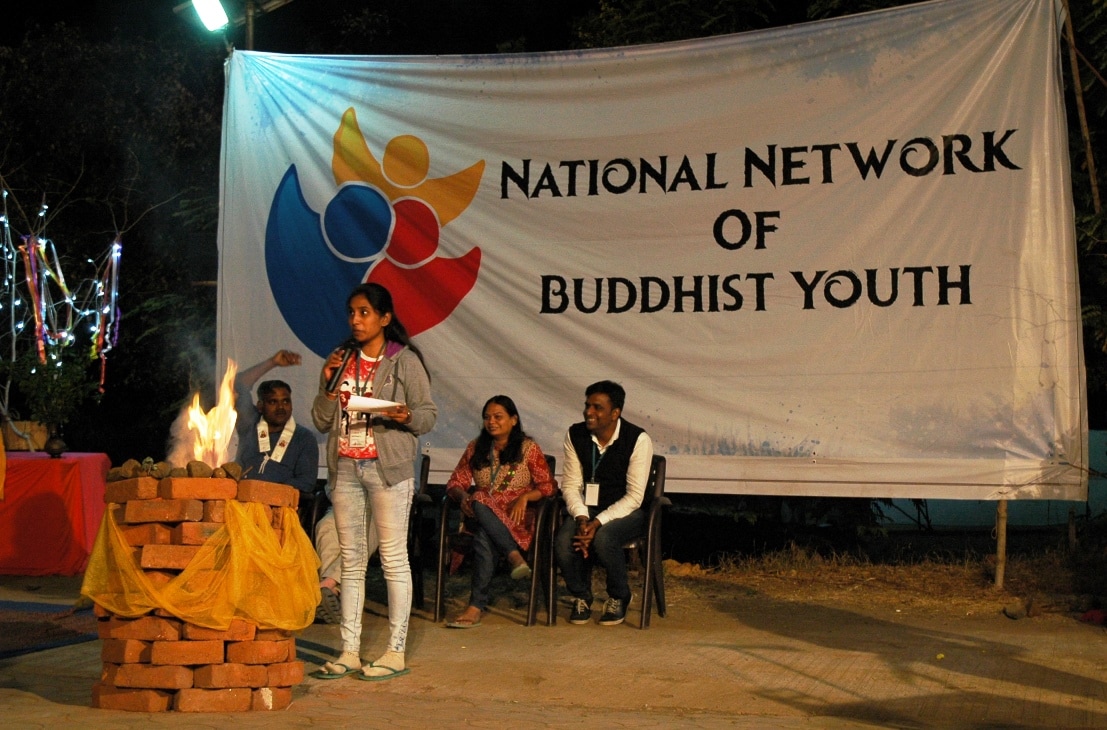

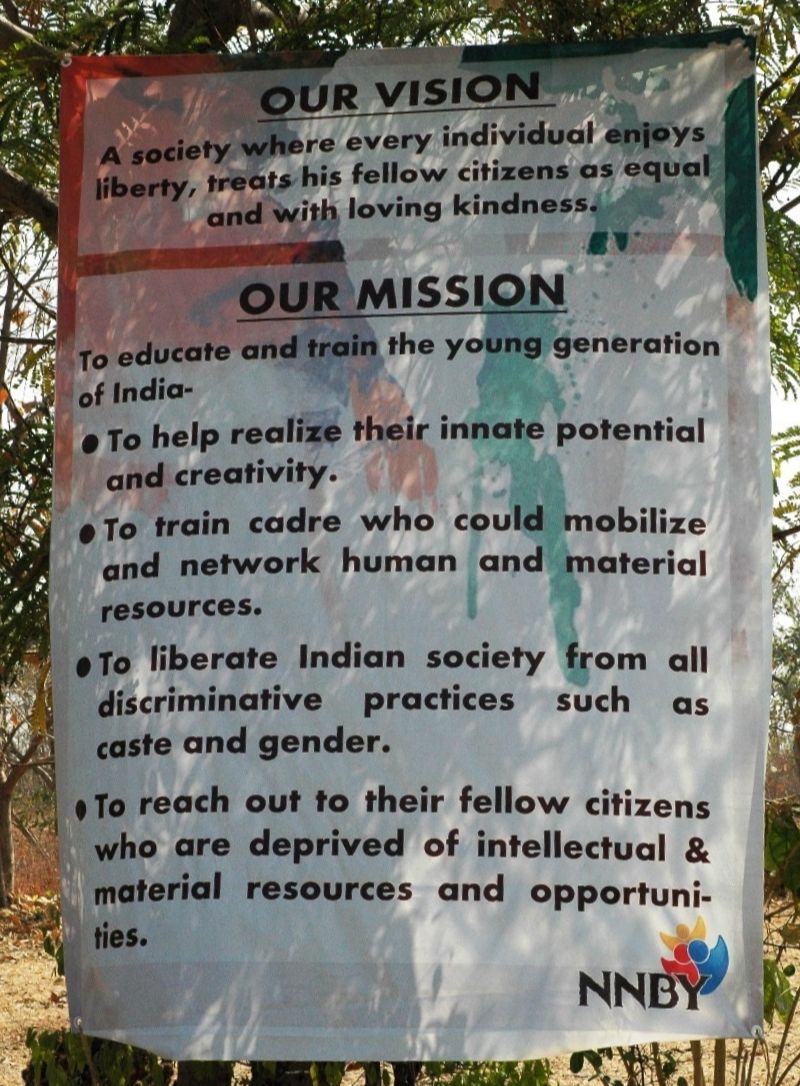

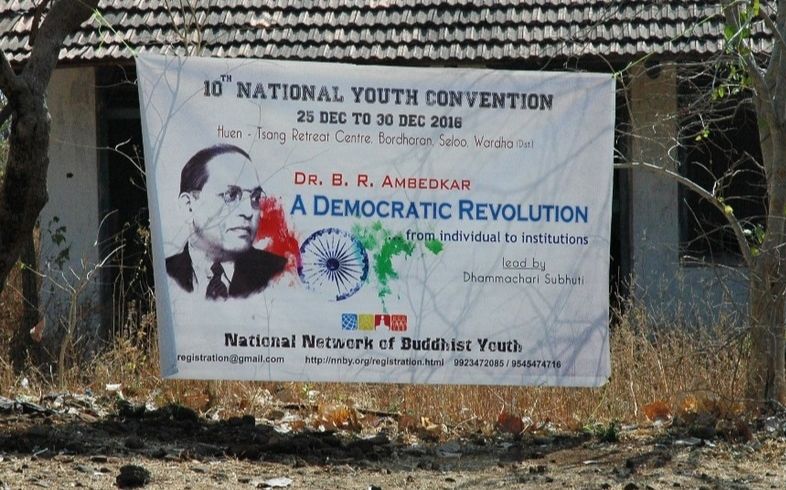

I have a habit, though, of not just noticing significant dates, but in being spurred to some action by them. I think it’s an extension of my poetic streak. As such, I am finally sitting down to write this on a date which will have a very different significance for my Buddhist friends in Nagpur, to my British (and more widely Western) friends, regardless of their religious persuasion. I am sitting down to write this on a date that perfectly illustrates my current phase of cultural transition. Today is April the 14th 2017. Today is Good Friday, the beginning of the Easter Weekend. That, in all honesty, doesn’t mean a lot to me because I am not currently in work, so I don’t need a holiday from it and I am not a Christian. I have; however, begun things in a traditional, English way by breakfasting on hot cross buns and choosing to dry up afterwards on a tea towel with a pattern of brightly coloured eggs printed on it. It’s not because I’m being pseudo christian (with a little c), or celebrating the death and reported resurrection of an historical figure. It’s not because I’m half-pretending to be in touch with my more pagan ancestry and tipping my hat to Eostre or the ancient fertility rights that come with the burgeoning spring. It’s not even, particularly, because I’m seeing it as an opportunity to celebrate new beginnings, the coming summer or the analogy of life, triumphant over the winter of death. I didn’t exactly experience what I’d call a winter last year anyway. No. I’m doing it because this year, more than any other, I am really, really aware of my roots. Not the dull kind, in the cruellest month of April, that Eliot stirred with spring rain in the Wasteland, but the ‘Oh wow, I never knew how bloody English I am!’ kind. I’m marking the Easter Weekend for no other reason than it’s what my family have always done, because that’s what English families do and because this year, I am really very glad to say I am a part of that. That’s certainly not due to any misapprehension that it’s better than any other way of doing things anywhere else but because it’s ‘me’ and ‘mine’ and pleasantly familiar and grounding and reassuring. This isn’t a tea towel with a gaudy design of cheery chickens and exciting Easter eggs. This is a cultural comfort blanket. However, while I am drying up with it after my very English breakfast, I am thinking a lot about Nagpur. I’m thinking about conditions, I’m thinking about the events and people that have brought me to this point. Last weekend I helped celebrate the 50th anniversary of the entire Triratna movement and so we talked a great deal about gratitude for Bhante Sangharakshita and all the things that have happened up until now for so many people to be benefitting from his teachings of the Dharma as he brought it to the West and started to share his knowledge of Buddhism in England. So today, on April the 14th 2017, it feels rather wonderfully synchronistic for me to be also quietly celebrating the birthday of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, the social pioneer, political activist and indefatigable philanthropist who led hundreds and thousands of his fellows from the oppression of the Hindu caste system into the liberty, equality and fraternity of the Buddhism. This he did finally, after a lifetime of selflessly struggling for emancipation, and sadly, just weeks before his death. Just as Bhante was in India, just when people suddenly needed someone to look to and to help them find the strength to continue Babasaheb’s work. Just as the conditions for this new movement were forming themselves and the Bodhicitta was stirring and swelling and moving. So that’s two reasons why the 14th of April 2017 is significant and that’s why, in between fleeting thoughts about how much I’m going to enjoy making shredded wheat Easter egg nest cakes this weekend, I am also thinking about my adopted culture and my Indian family and that’s why when I finished drying up my very English breakfast, I sat down, finally to write about how I came to know just how very English I am. Eliot didn’t just write about ‘mixing memory and desire’ after all, he also wrote about travel and how, at the end of it, we shall return to where we started and ‘know it for the first time’.

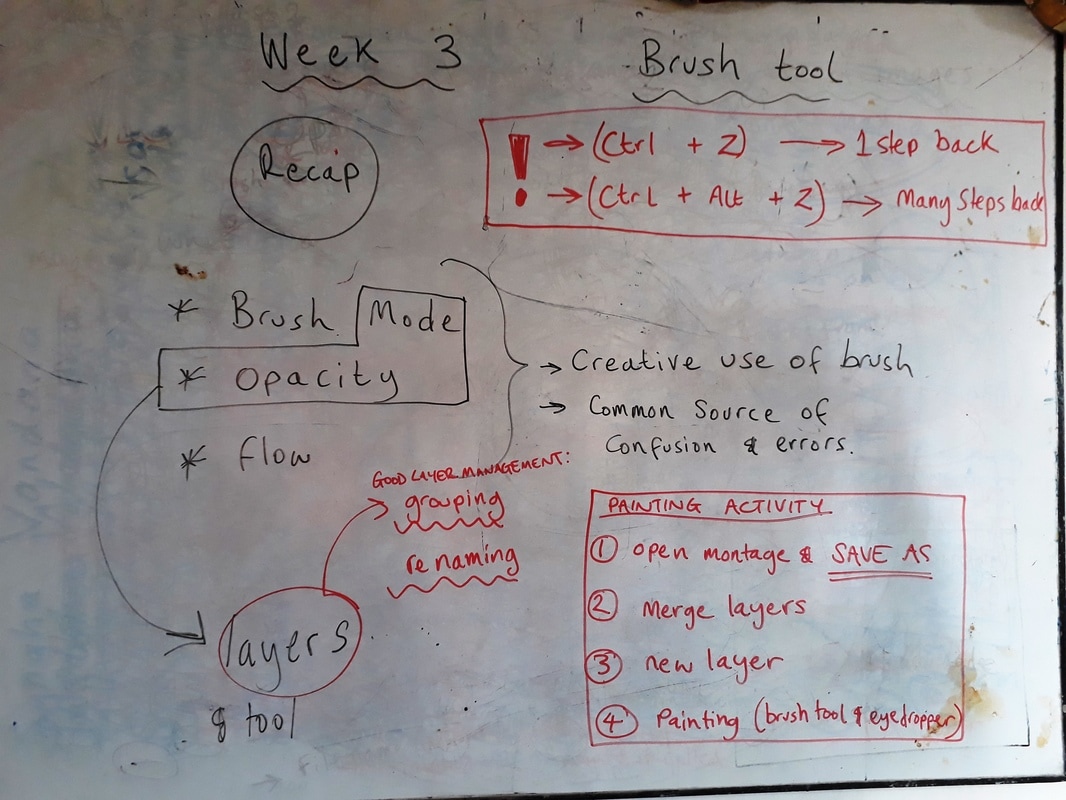

I was the ‘last one standing’ on our teaching team, after Shakyajata and Mark both headed back about 6 and then 2 weeks ahead of me, respectively. I knew, having spent the last five months trying to get my head around Indian planning, that no matter how carefully or meticulously I planned that remaining time, it was not going to end up playing out quite as I hoped in reality. Shakyajata had made it clear that what the students still really needed was help writing CVs, looking for jobs, preparing for interviews and maybe a bit of handwriting practice. In theory, that was all totally fine. Nothing I hadn’t done before, year after year in tutorial groups. In England. Where I knew a bit more about the job market and the application ‘norms’. In India? Goodness knows. I’d discussed some of my concerns in this area with the ever supportive Mark just before he left though, and he’d very wisely counselled me that perhaps the most important thing to consider, the best ‘parting gift’ I could give to the students was not necessarily academic but social. Human. ‘Just spend time with them’ he suggested. ‘Don’t worry about the teaching, don’t get stressed. Just finish on a positive note.’ There can’t have been a more useful word written in the most academic of teaching resources and though I didn’t want to feel I’d ‘given up’, I did recognise that dragging everyone kicking and screaming through a series of activities because ‘that’s what it SAYS on THE PLAN!’ Would be doing no one any favours. In fact, that would be scarily reminiscent of the criticisms I had of the UK education system that had lead me to leave it and wind up trying to decipher and teach grammatical voodoo magic in Nagpur in the first place.

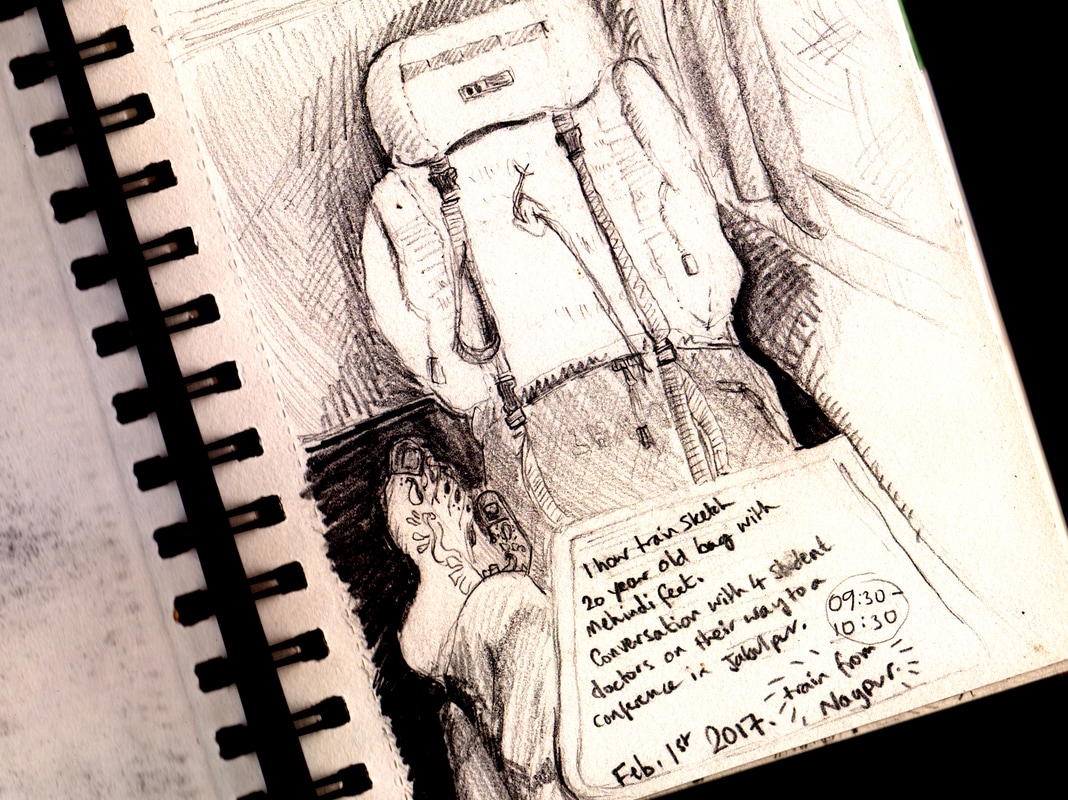

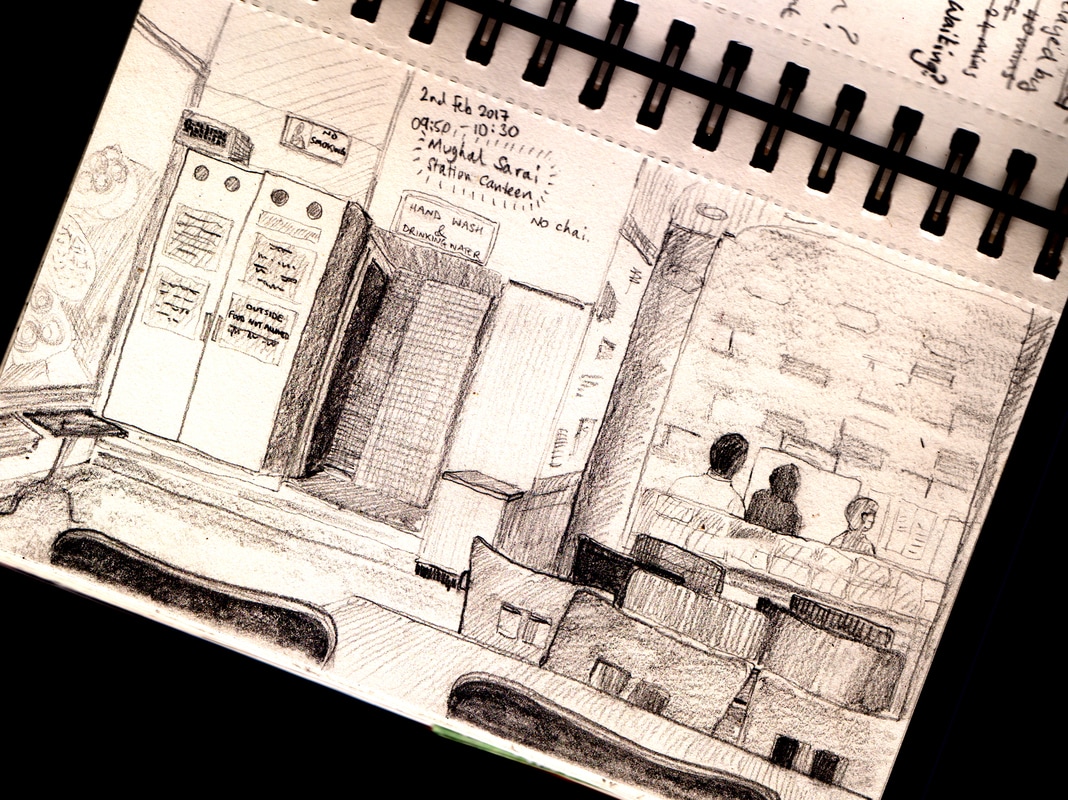

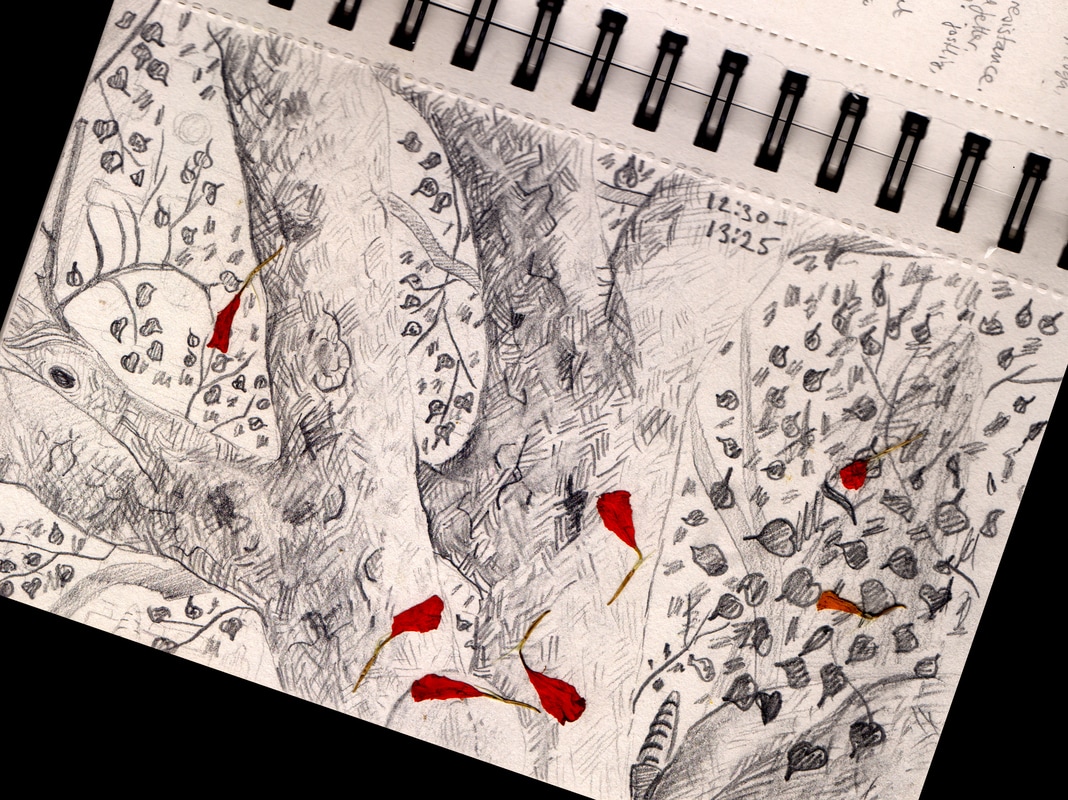

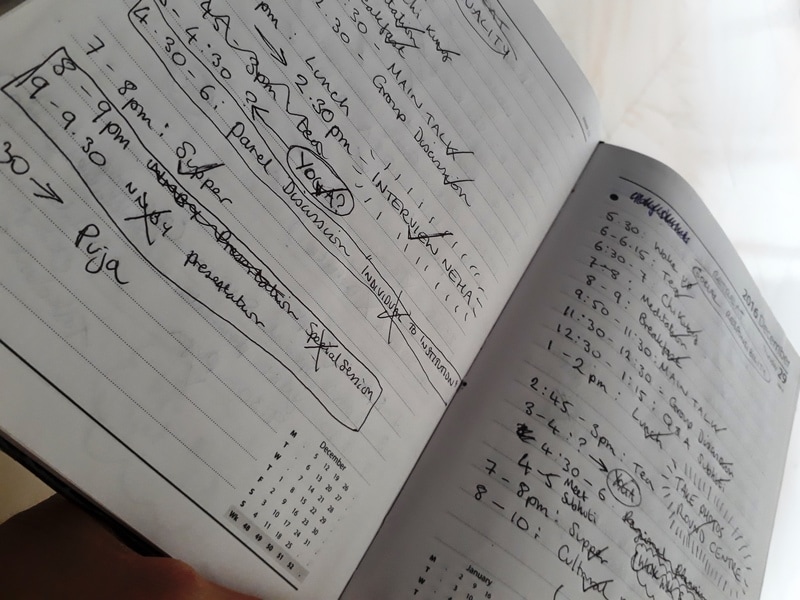

| It was just as well his advice resonated with me. What with Hardware and Networking revision classes, the exams themselves, Tally practice and exams, MS-CIT resits, and even educationally unrelated things such as random centre closures for city elections, there was far less formal classroom time available than I had anticipated, even when taking ‘the unexpected’ in to account. It would have been very easy to worry about this and feel I was not providing what I had been asked to deliver, but, with Mark’s words in my mind and a few reassuring emails from Shakyajata, I was able to relax, let go a bit and respond flexibly to the reality, rather than agonise over the unrealised planning. We did, in the end, do enough. We did some work on CVs and we wrote, reviewed and typed some personal statements. We talked about how to find and apply for a job, we filled in some practice application forms, talked about black ink and ‘block caps’ and what N/A means. We chatted about how to prepare for and give a good interview, we briefly role played answering some daft questions. And then, around those shreds of ‘teaching’, we had fun. We enjoyed spending time together, and I finally, finally, eased off my expectations of what people might expect of me (which they probably didn’t anyway) and gently let go of the ‘professional’ conditioning that says you don’t socialise or share things with students. I then began a concerted effort to wring every last drop of these things out of the rapidly evaporating hours. I went to market to buy groceries with the girls. I asked them to alter a sari for me and teach me how to wear it, as in actually get dressed myself. I was finally brave enough to sample their strange deep-fried biscuits and I let them paint my feet, Bihar style with pink alta. They painted my nails and drew ornate designs up my arms with henna. I didn’t get to run the ‘positive body image’ tutorial work shop I had started to plan, but I did have dinner with them and when I established that the conversation had run into areas such as ‘but you are fat and she is skinny’, I adlibbed a rather poetic series of rhetorical questions about whether a tiny, delicate jasmine flower was more beautiful or valuable than a soft, voluptuous rose, (and anyway didn’t they both smell just as fine?), before standing, hooking my rice-and-chapatti replete belly out of my salwar and pinching my gut up and down to make my belly button mouth along to my loud exclamation ‘I’m proud to be me!’ “Good example, Ma’am!” Hemlata commented, when the company had finished dissolving into fits of giggles. I realised I didn’t know, until I actually spent time with her, that her English had got so good. Of course it wasn’t all about the pleasure of receiving their hospitality. I devised, sourced and prepared an ‘English Style’ picnic, with cucumber sandwiches (crusts off!), peanut butter (on brown) and strawberry jam tarts. I don’t think I’ve ever put so much effort in to planning a ‘cultural awareness tutorial’ as I did into working out how to cook jam tarts without an oven. I introduced them to Marmite, but no one really thanked me for that. After about 15 minutes of trying to persuade Madhu that yes, I really had made all this ‘gourmet cuisine’ myself, I finally asked why she was in such disbelief. “Because she didn’t believe anyone would go to so much trouble for them” was Sheetal’s translation of her sadly moving reply. Half choked with pathos, half cresting the wave of appreciation, the next day I spent 3 hours scouring various supermarkets and ‘expat shelves’ and on our final night together, I cooked them a pasta party with spaghetti Bolognese, tomato penne, a pasta-bow salad, garlic bread (read garlic toast, I did my best), a green salad and a summer pudding. Sort of. As much as you can prepare a summer pudding without summer fruits. I probably spent about six times as much cash on that feast than I spent on an entire 5 months of photocopying and printing class resources. I lived in the same house as the girls of course, so it was easier to spend more time with them and the boys drifted off in dribs and drabs as they returned one here, two there to their home villages to sit the government exams required of them in their own states. There was time for those who remained; however, and it was thanks to the men, not the women (no stereotype enforcement here!), that I now know how to cook poha (flattened rice flakes cooked with potato, tomato and chilli) for breakfast and can just about prepare a batch of chapattis (I’ve stopped setting fire to them now). We chatted a lot about the Dharma. I bought them expensive coffee. I took them to Pizza Hut (Hey, my dad used to work for Pizza Hut, it’s practically in my genes!). We walked round town and went on the swings (who can get the highest!?) and visited the science museum to sit through a ‘planetarium show’ that turned out to be a very poor computer animation of some under the sea scenes in a rundown theatre of a battered, ancient exhibition centre that still had displays heralding the arrival of the internet. |

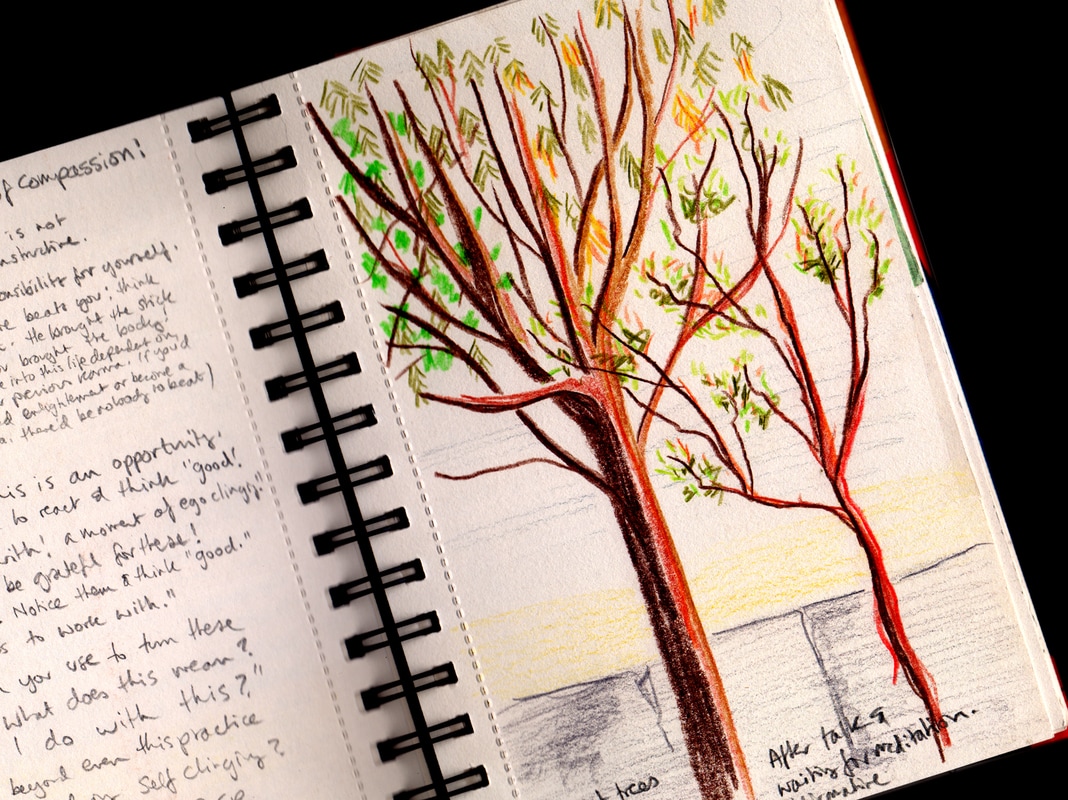

| When the students had all finally departed, I then spent time with the family I’d lived with that whole time. Sheetal and I went shopping, bumping up and down on the back of her scooter for the last few times. We visited the Deekshabhoomi to say ‘goodbye’ to Babasaheb’s stupa. We splashed around at a water park that resembled an aquatic version of those photos you see of the abandoned fun fair in Chernobyl. We went for more expensive coffee. I tried to make cookies on the hob; I made flat scones. Everyone agreed the jam tarts were better. I made a ‘Chinese’ that ended up having too much chilli in it even for Aryaketu and Ojas. I thought it was fine. I finally tried to make bread in a pressure cooker with the yeast we bought about a week after I arrived. The cows enjoyed a rather stodgy breakfast. What I learned (as well as just thoroughly enjoying my final fortnight) was that you can’t formalise real sharing. You can’t prescribe or manipulate a genuine connection. It is not possible to ‘plan and deliver’ that ‘content’, you just have to be. You simply have to be content to be you, with others; as interested and accepting of their version of the mundane as you are willing to spend time demonstrating and exemplifying yours. It’s not in the heights of academic discourse that we exhaust the limits of our commonality. We bond over the hilarity of the failed bread and we forge friendships in a dripping heap at the bottom of rickety old water slides as we share stories about summers long gone, before we learned to be scared of the foreigners. So much of that flies in the face of what I’ve been trained to do. It took me five and a half months to unlearn that when a student is crying, they must under no circumstances be hugged. It took me nearly my whole stay to remember that the best teachers are the ones who are confident enough to say ‘I don’t know the answer to that question. But I’ll show you how we can both find out.’ I still feel like a slightly suspicious and potentially untrustworthy liability when I accept a student’s friend request on Facebook. But why? We are, after all, friends. It strikes me as somewhat significant that I am gradually letting go of all this interventionist and ultimately well-meaning but fundamentally dehumanising policy against a background of heightened awareness of the need for safeguarding in the Triratna community. The movement has recently been re-engaging with a history of controversy, allegations of abuse and openly admitted failings in the backstory of a (very young) order that are now resulting in discussions around how to protect the vulnerable and challenge those who would manipulate them. Yet again I find myself realising that in this, as in all things, it is a question of balance. We must accept and address our human potential to fail, to mess up, to hurt each other, but please, never let this be at the cost of the genuine expression of honest, wholesome, friendship and affection. So that, as they say, was that. That’s a potted summary of the final fortnight of my twenty two weeks in India. But can I give a meaningful summary of my key experiences? Can I provide an insightful reflection from the perspective of my homecoming? Honestly? I don’t know where to start. Nothing’s scared me more in recent weeks than the enthusiasm of friends who ‘can’t wait to hear all about it!’ |

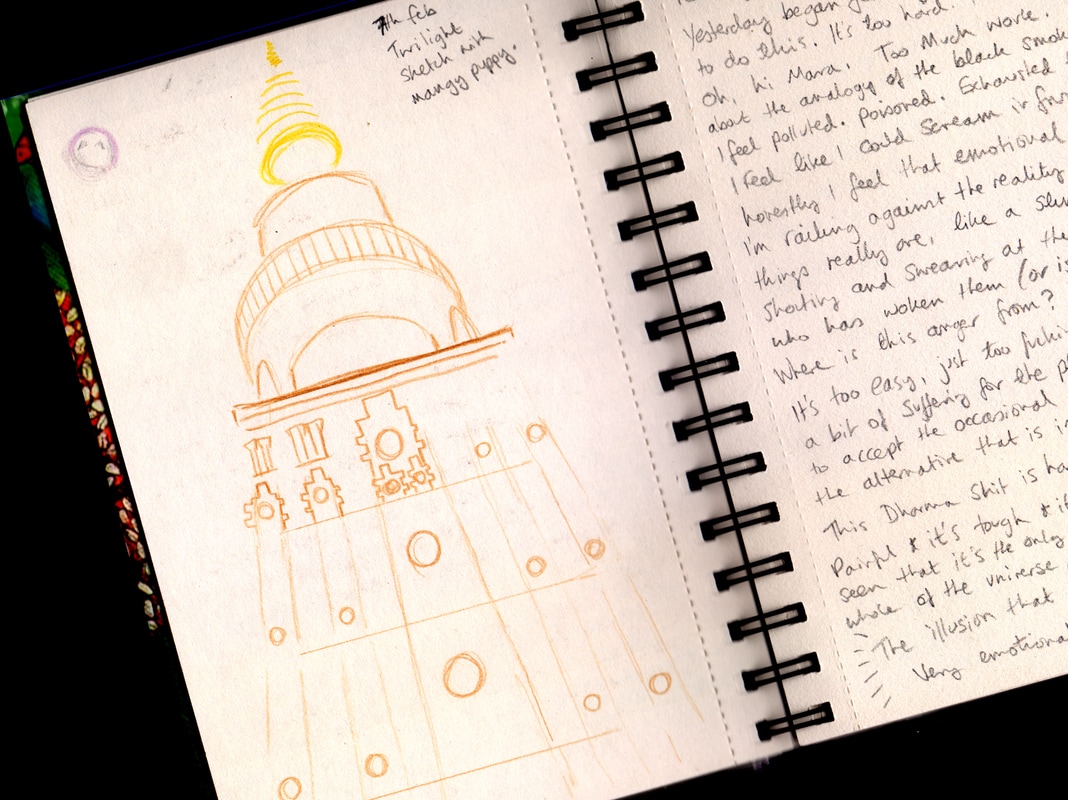

How can I possibly put that in to words? I mean, I’ve tried, obviously. I’ve poured as much articulation of my experiences as I’ve been able into this blog and it’s (semi)regular updates. I’ve spent literally days writing, re drafting and finally publishing 25 (whoops, 26!) of them, often several thousand words a post, some with their own chapters, all with carefully selected and sometimes edited images. But they are weak, supermarket own-brand blackcurrant cordial filled beakers of my words, placed next to the crystal goblets of Châteauneuf-du-Pape that have been my experience. They don’t come close.

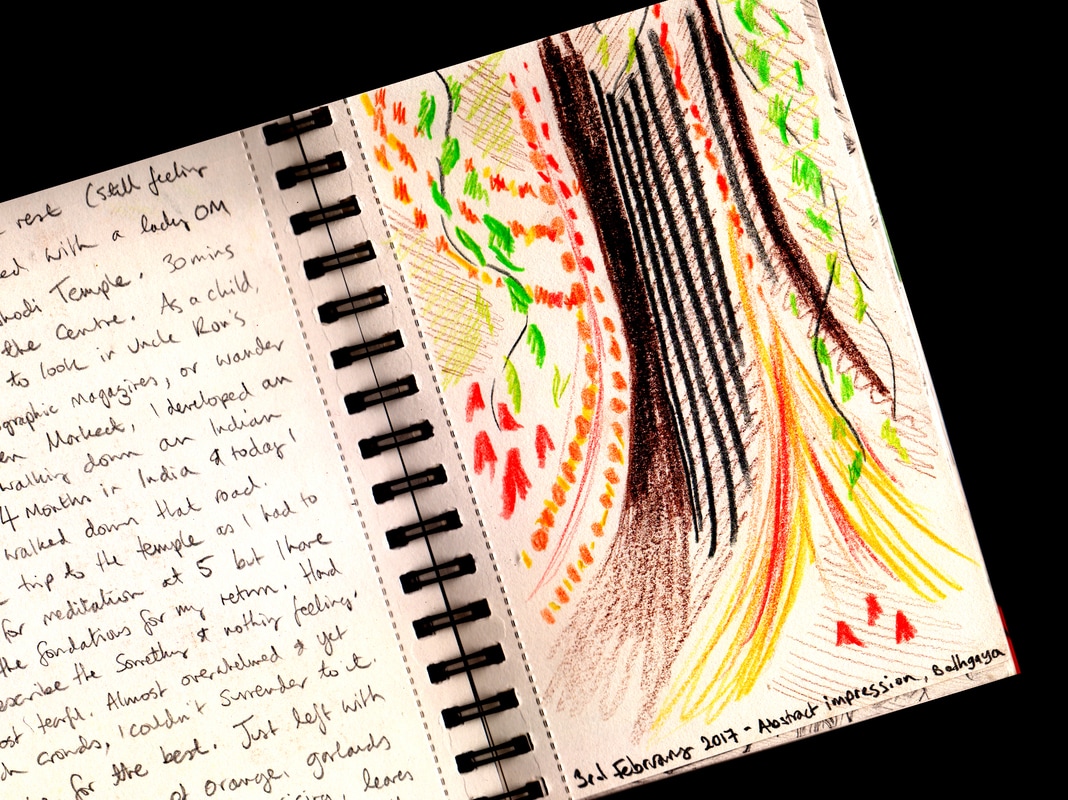

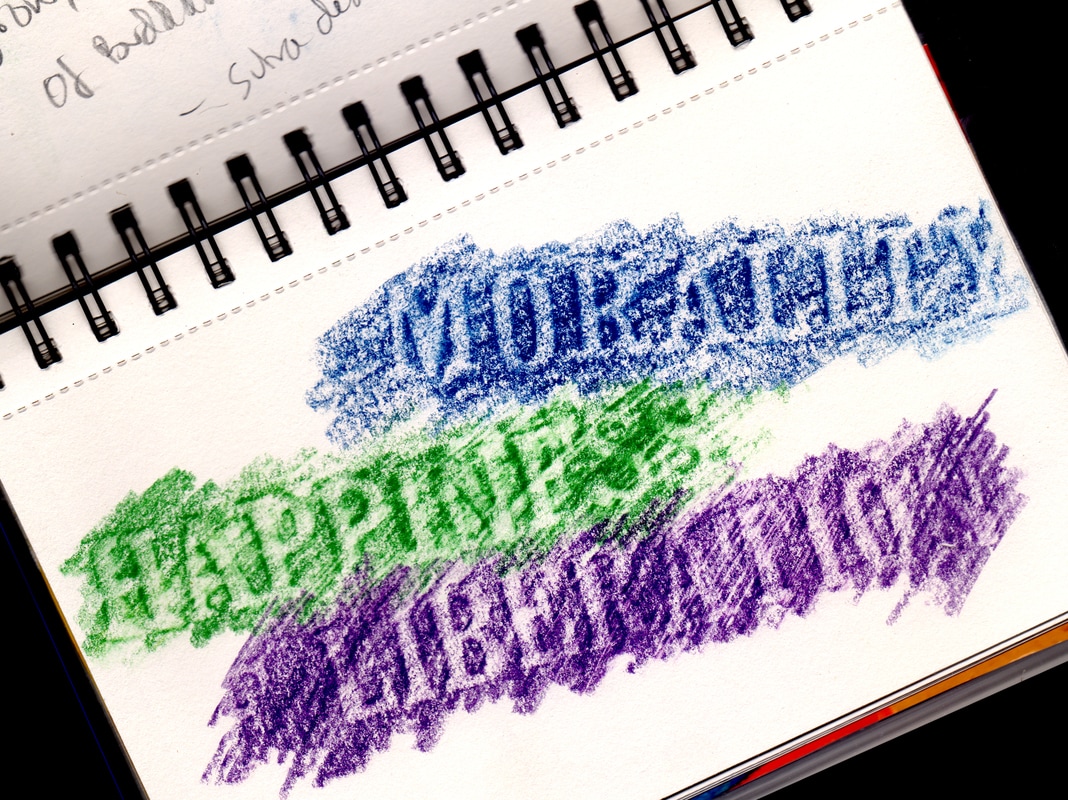

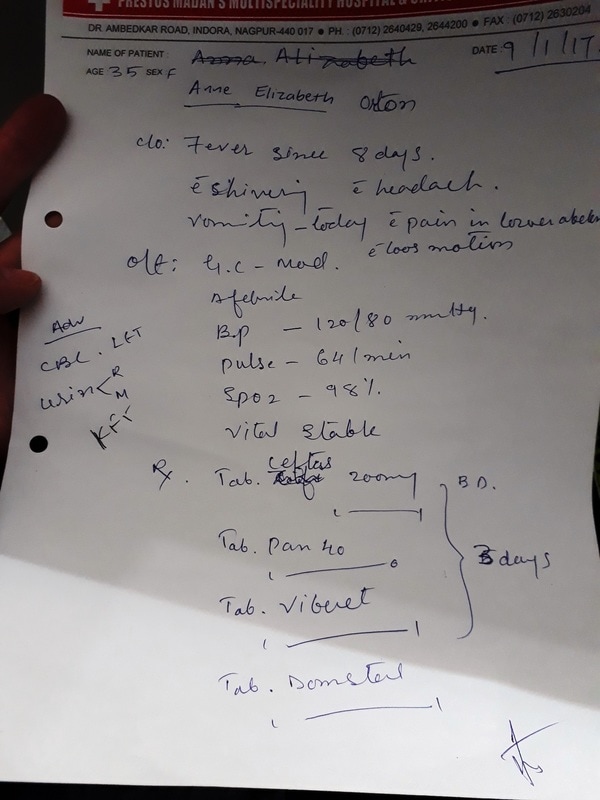

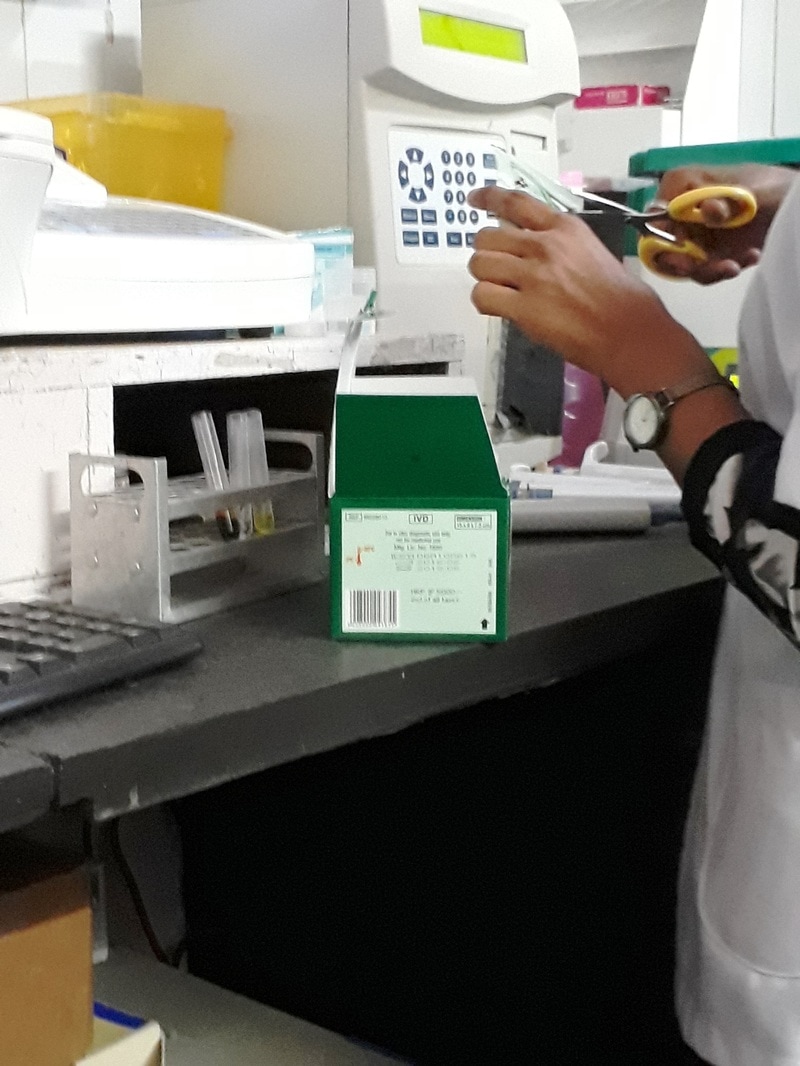

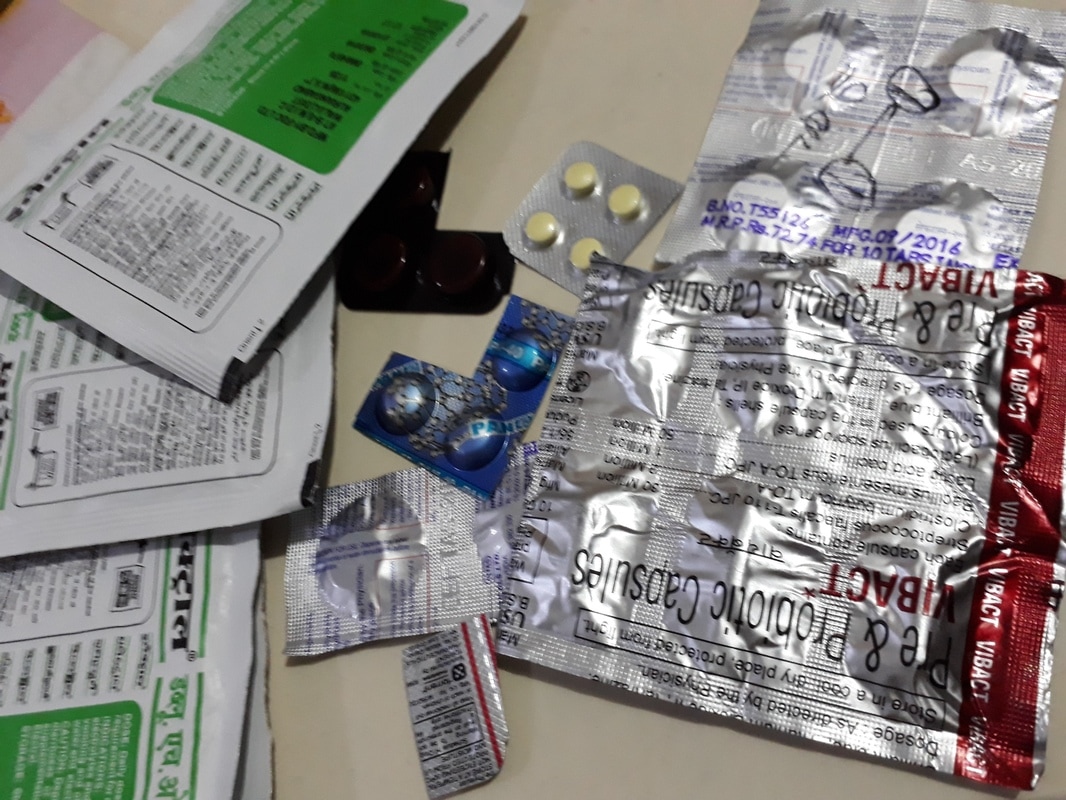

I’ve been moved to frustrated tears of spiritual discovery under the Bodhi tree, I’ve narrowly escaped near disaster on remote hillside paths, I’ve learned not to bat an eyelid as I cross roads where the traffic never stops and I’ve developed the ability to wee, in a sari, over a hole in the ground, without getting wet feet or falling over (mostly). I’ve listened in horrified silence to personal stories of oppression, debasement, exclusion and torture in the name of religion, divinity and tradition. I’ve experienced spiritual death in the countryside, spiritual rebirth in the city. I’ve laughed until I nearly lost control of my bladder and wept until I thought I’d be sick. I’ve felt energised, I’ve felt exhausted, I’ve felt healthy, I’ve felt ill, been in hospitals where patients are treated next to piles of bloody rags, but where you get to watch your own samples being analysed in the laboratory. I’ve been on a shot-to-the-heart roller-coaster-ride of cultural pugilism. I’ve felt so happy I might evaporate one minute and I’ve felt cut to the quick, so hopeless I might dissolve the next. I feel like I’ve spent the last six months ignoring the dilution instructions on the high juice of life and elected to drink it straight from the bottle. I’ve had experience concentrate flowing in my veins. But what have I learned?

I’ve been moved to frustrated tears of spiritual discovery under the Bodhi tree, I’ve narrowly escaped near disaster on remote hillside paths, I’ve learned not to bat an eyelid as I cross roads where the traffic never stops and I’ve developed the ability to wee, in a sari, over a hole in the ground, without getting wet feet or falling over (mostly). I’ve listened in horrified silence to personal stories of oppression, debasement, exclusion and torture in the name of religion, divinity and tradition. I’ve experienced spiritual death in the countryside, spiritual rebirth in the city. I’ve laughed until I nearly lost control of my bladder and wept until I thought I’d be sick. I’ve felt energised, I’ve felt exhausted, I’ve felt healthy, I’ve felt ill, been in hospitals where patients are treated next to piles of bloody rags, but where you get to watch your own samples being analysed in the laboratory. I’ve been on a shot-to-the-heart roller-coaster-ride of cultural pugilism. I’ve felt so happy I might evaporate one minute and I’ve felt cut to the quick, so hopeless I might dissolve the next. I feel like I’ve spent the last six months ignoring the dilution instructions on the high juice of life and elected to drink it straight from the bottle. I’ve had experience concentrate flowing in my veins. But what have I learned?

One key thing I’ve learned is that I don’t represent anything other than me. I am not a sex symbol (really), nor a symbol for my sex. I am not ‘one of them’ (one of who, incidentally?). I am not one of ‘you people’. I do not represent ‘women’, I am not speaking for ‘the westerners’. I am not, for that matter, speaking for Europeans, the British or the English. I’m not even speaking for other white, single, pierced, vegan, female, recently converted Buddhists who grew up in London in the 1980s, like running, reading and drawing, eat too much sugar, drink too much coffee, have a weakness for cats a romantic predilection for walking on beaches on starry nights and have perfected the art of the crispy skinned, fluffy centred, humble baked potato. I’m not sorry to say, that really all I’m doing is speaking for me. I’m not even totally sure I’m doing that particularly reliably a lot of the time. I might try and speak up for someone, but that’s not the same thing. I am not, nor will I ever be a generalisation.

I have learned (once again but in a different way) that it doesn’t matter how many miles you put between you and the apparent source of your unhappiness because the demons you’d like to blame it on are inside your head and the chances are, you’ll be bringing that along with you. Demons are most definitely not excluded from your cabin bag. In fact they really quite like a trip out and are very happy to come along to play. You’ll have to do something a bit more creative if you want to make peace with them, like listening to what they are actually trying to tell you, without sticking your fingers in your ears and going ‘la, la, la, I’m too grown up to listen to you!’

I have learned (or at least confirmed my suspicion) that I am extremely English. I maybe a particularly open minded, broadly experienced version of one but there’s no doubt at all that I am an Angle, through and through, from my tendency to burn in the sun to my persistence in trying to queue for things even when no one else does, right down to my almost genetic need for nice predictable planning that we stick to. Yes, it’s true, I like vinegar on my chips and a cold sea breeze in my face and nice warm socks on my clean, dry feet. But that’s OK. Those are things that shape my perception but they are not, at the end of the day, the things that define my capacity to be a responsive, compassionate human being. They influence but they do not limit me.

I have learned, genuinely, surprisingly, for the first time in my life, that actually, I am a feminist. I have also learned that I have an absolute responsibility now, to do something about that. I haven’t learned how I’m going to do that yet, but I have time.

I have learned (once again but in a different way) that it doesn’t matter how many miles you put between you and the apparent source of your unhappiness because the demons you’d like to blame it on are inside your head and the chances are, you’ll be bringing that along with you. Demons are most definitely not excluded from your cabin bag. In fact they really quite like a trip out and are very happy to come along to play. You’ll have to do something a bit more creative if you want to make peace with them, like listening to what they are actually trying to tell you, without sticking your fingers in your ears and going ‘la, la, la, I’m too grown up to listen to you!’

I have learned (or at least confirmed my suspicion) that I am extremely English. I maybe a particularly open minded, broadly experienced version of one but there’s no doubt at all that I am an Angle, through and through, from my tendency to burn in the sun to my persistence in trying to queue for things even when no one else does, right down to my almost genetic need for nice predictable planning that we stick to. Yes, it’s true, I like vinegar on my chips and a cold sea breeze in my face and nice warm socks on my clean, dry feet. But that’s OK. Those are things that shape my perception but they are not, at the end of the day, the things that define my capacity to be a responsive, compassionate human being. They influence but they do not limit me.

I have learned, genuinely, surprisingly, for the first time in my life, that actually, I am a feminist. I have also learned that I have an absolute responsibility now, to do something about that. I haven’t learned how I’m going to do that yet, but I have time.

I’ve learned the nature of being more privileged than I truly realised, but sort of suspected I might be. I’ve learned, embarrassingly, that simply because I was born with the genes to produce less pigment in my skin than some people, there is a vast swathe of the planet’s surface where a majority of its inhabitants will always be willing to prioritise me, usher me to the front of the queue (where there is one) and listen to me with rapt attention, regardless of how half-baked and barmy whatever it is I might have to say could be. I’ve learned I have a responsibility to respect that audience and say things that will be useful to them. I’ve learned with humility that I will never be so poor I have to choose between healthcare and a meal, between safety and dignity, between free will and a secure place to call home. I will benefit, for my entire remaining life, from never having suffered the crippling personal disability of being denied an education because of who my parents were. But then I’ve also learned that ‘privilege’ is a slippery concept, a movable benchmark that is entirely dependent on your perspective. I’ve learned that some communities are fighting through financial poverty, but some, in other parts of the world are battling emotional poverty, social deterioration and psychological need, which is perhaps not so easy to fix with charitable donations. I’ve learned, that perversely, sometimes too much privilege can be just as damaging as not enough. The opportunity to compare the achievements of young people with a sense of entitlement to education against those who’ve fought tooth and nail to get anywhere near it, has taught me that we often only value that which we’ve had to work for. I’ve learned that the apparently honourable acceptance with which some people appear content to live a simple, basic existence can be misleading when viewed from the eyes of those who feel the strain of an overly complicated life of excess and hedonism. Apparent renunciation and the discipline of a frugal lifestyle is hardly honourable if you’ve never had any wealth or excess to renounce.

There’s more, of course; I have learned that the UK society is a LOT more equal and diverse than we might think or even aspire to. I thought, when I moved from London to Manchester, that I knew homogenised communities for the first time, but that’s nothing compared to some places and a majority of British people are not entirely as prejudiced or xenophobic as we seem to think we are. We are not the only nation to fear the alien, the other, the slightly unfamiliar, nor are we the only people to foster massive generalisations about anything slightly foreign. I’m not for even a split second suggesting that’s a reason to stop working for change, and tolerance and liberation, but I think we’d sometimes benefit from recognising and celebrating just how far we’ve already come, on a global stage.

I’ve also noticed that for all our inherited inequalities, we LIKE an underdog. Yes, our society is divided into classes that struggle and have wars and exist in the relative strata of have and have not but nowhere in our culture do we ever say you can’t achieve a life beyond that if only you work hard enough. No, it’s true, it’s not fair that we don’t all start with the same resources and we don’t all get the same breaks in life but no one in post war Britain grows up terribly far from the idealism that with enough welly (and maybe a pinch of luck), you’ll get there, wherever that might be. It may be regrettably materialistic in nature but whoever you are, you’re only ever a winning lottery ticket away from a comfortable life, social status and maybe even a little respect and envy. Yes, you might struggle to break into certain professions because your family can’t easily afford the specialist education to get you there but you’ll never be told that you have to do a certain job because of your surname. You’ll never be told (by anyone society deems worth listening to, anyway) that you should accept the conditions of your birth as a reason not to aspire to better things, that your worth as a human is signed and sealed in your father’s name, on a birth certificate in permanent ink that cannot be changed.

There’s more, of course; I have learned that the UK society is a LOT more equal and diverse than we might think or even aspire to. I thought, when I moved from London to Manchester, that I knew homogenised communities for the first time, but that’s nothing compared to some places and a majority of British people are not entirely as prejudiced or xenophobic as we seem to think we are. We are not the only nation to fear the alien, the other, the slightly unfamiliar, nor are we the only people to foster massive generalisations about anything slightly foreign. I’m not for even a split second suggesting that’s a reason to stop working for change, and tolerance and liberation, but I think we’d sometimes benefit from recognising and celebrating just how far we’ve already come, on a global stage.

I’ve also noticed that for all our inherited inequalities, we LIKE an underdog. Yes, our society is divided into classes that struggle and have wars and exist in the relative strata of have and have not but nowhere in our culture do we ever say you can’t achieve a life beyond that if only you work hard enough. No, it’s true, it’s not fair that we don’t all start with the same resources and we don’t all get the same breaks in life but no one in post war Britain grows up terribly far from the idealism that with enough welly (and maybe a pinch of luck), you’ll get there, wherever that might be. It may be regrettably materialistic in nature but whoever you are, you’re only ever a winning lottery ticket away from a comfortable life, social status and maybe even a little respect and envy. Yes, you might struggle to break into certain professions because your family can’t easily afford the specialist education to get you there but you’ll never be told that you have to do a certain job because of your surname. You’ll never be told (by anyone society deems worth listening to, anyway) that you should accept the conditions of your birth as a reason not to aspire to better things, that your worth as a human is signed and sealed in your father’s name, on a birth certificate in permanent ink that cannot be changed.

| Finally (you’ll be pleased to know), and with some surprise, since coming home, I’ve learned that sometimes the little personal or domestic ‘duties’, the changes we can make close to home are every bit as revolutionary as the stuff we do that stretches over continents and demands answers from global superpowers. Before I left for India, I had been staying with my (almost 84 year old) bachelor great uncle, indeed, I published a poem and a new series of photos of his home shortly before I went. He supported me with a couple of rent free months and a place to store all the junk I couldn’t quite bring myself to give away or chuck in a charity shop while I was gone. Two weeks before I flew back, he was taken into hospital and so what I had anticipated as a rather roomy period of time to vaguely drift about the country visiting all the friends I’ve been promising to drop in on for years as I tried to postpone a sense of obligation to ‘settle back down’, instead became a short, sharp return straight to his house, where I have been ever since. My time has been concerned with helping him keep track of his medication, and assisting him with liaising between the different agencies that are tasked with supporting his independent recovery in his own home. I’ve been helping, in return for somewhere to live, of course, with basic domestic needs and I’ve taken responsibility for trying to coax a severely diminished appetite back into existence with creative applications of mayonnaise, strategically placed digestives and deliberately timed Cup-a-Soups. The ‘get a cheap tent and walk round the UK because I can’t afford the travel’ plan was probably never a very good one anyway, though in hindsight, it probably wasn’t one of my craziest. Sure, helping round the home of someone with the frayed temper of one in constant pain for whom I normally have to repeat sentences at least 3 times, isn’t always reminiscent of a Butlins Holiday Camp, but I’m very, very happy to be doing it and I’ve been somewhat saddened by the surprised response of those who seem to view it as some kind of martyrdom or heroism on my part. Here is a human being, whom I happen to love and care for, who has helped and supported me, who now needs my help and support. I do not have any commitments or responsibilities that I cannot flex around meeting these needs. Why wouldn’t I do all I can to facilitate this? Perhaps it’s because I’m fresh from a country where this would never be a problem because families literally live three generations to a roof that it seems strange to question it, but I think it’s a sad symptom of a society increasingly fractured into selfish and insular units that value the hedonistic ‘me, me, me’ quick-fix, excite-and-move-on fast track, disposable gratification lifestyle, that so many people consider caring for your elderly relative to be something even worth remarking upon. So I am being the change I want to see in the world and I am quietly getting on with a private revolution in what might appear to be a conservative but has apparently now become an alternative lifestyle. |

Oh yes. One last thing. I’ve learned to appreciate silence. I’ve always liked but now I’ve learned to love a clean, organised street lined with daffodils and hawthorn shoots and quiet enough on an early Sunday morning that you can almost hear the blossom falling off the cherry trees onto the damp grass below. I’ve learned that nothing sounds quite as much like home as the self-satisfied chortle of a big fat wood pigeon stuffed to the beak on old bits of dry crumpet.

| And so that was the end of the course. The increasingly distant completion of my time trying to teach English in India and my reflections upon it. It wasn’t a fixture in a diary, it wasn’t a note on a calendar. It came like the fading out of a ballad or a short film fogging away into the mist of a blank screen. It didn’t really happen, it just gradually drifted from future tense, to present perfect progressive, to future perfect progressive and then, simply past. See, I did learn some grammar. (Nah, I lied, I had to look that up.) I was sort of aware of this process, of course, and aware that I should be feeling emotional about it all somehow, this slow, slipping away. In India, people generally live much more up against their own emotions, or at least there’s an expectation that one should be quite clear about demonstrating these in certain contexts. My Stiff British Upper Lip didn’t quite get with all the weepy-wailing on several occasions and left me feeling as though I was somewhat cold or lacking. When I waved goodbye to Shakyajata for example, unlike all the students waving her off, I didn’t cry. When I said goodbye to Mark and left him at his farewell dinner with the rest of the young men he’d been living with, I certainly didn’t cry. Actually, I think I punched him on the arm before shouting ‘you smell anyway!’ and running out of the crowded restaurant only to emerge through a bush moments later on the other side of the window where he was sitting and treating him to my finest piggy nose on the glass. Well, I never pretended my expressions of affection were particularly ‘normal’. Sure, I felt a little uncomfortable saying goodbye to our young women’s community and since they all left on the same day, their absence left a palpable vacuum, but I didn’t cry. I wished the departing members of the men’s community good luck for the future with firm handshakes all round, but I didn’t cry. The morning I left the family home, the moment I waved goodbye at the airport, I felt a tug of detachment. But I didn’t cry. 24 hours later, I landed in Manchester on a cold, grey, Saturday dawn and stood on the ‘UK border’. How you can have a border in the middle of a suburban airport, I have no idea but still, I stood under the signs for it with my passport in hand and I didn’t cry. Later, I met my friends, I went to the Manchester Buddhist Centre, I found and hugged (broadly speaking) my ‘original’ Sangha; I didn’t cry. Still later that day, another farewell, to Manchester for London, on a Virgin train. I didn’t cry. |

By the time I arrived in Leigh on Sea that night, across two tube changes and a C2C train, I was so tired, I might have burst in to tears at any point but when I got through the door and I saw my mum and my uncle; you know what I didn’t do? Right. I didn’t cry. So that was that. The imagined Facebook status update that went something along the lines of ‘…and then my face dissolved into a weeks’ worth of wet washing’ never got an airing. The Ice Queen reigned supreme.

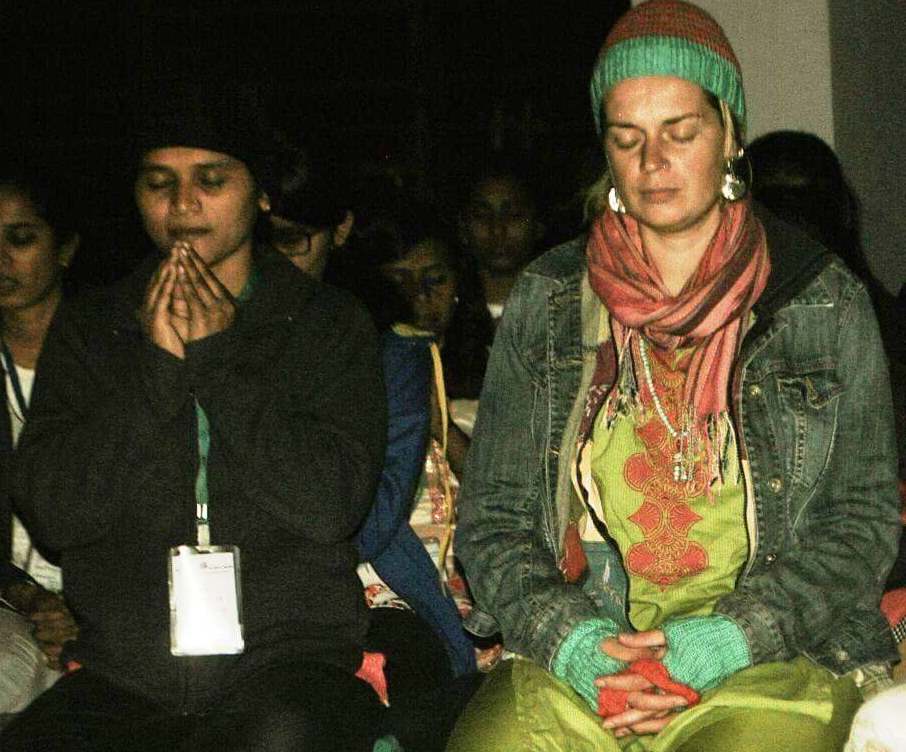

Three weeks later, and I finally engineered the time and the train fare to head back into London for a meeting at the Triratna centre in Bethnal Green. I stepped in to London Buddhist Centre courtyard and the familiarity, the placid, unchanged calm, triggered a genuine flood of raw emotion, finally given a point of release. Here, my brain eventually threw caution to the wind and necked shot after hard core shot of relief, gratitude, compassion and love until I was quite drunk in an aura of fuzzy, warm, positive emotion. As I removed my shoes and hung up my coat, this vague yet forceful release distilled itself into an awareness of where I am coming from and what I had just done. An acknowledgement of the events I had been a part of and the commitments I have made, all set against the backdrop of the sheer unadulterated brightness and joy of what my future holds, despite the difficulties I still work with, despite the days I find hard. I really knew then that no matter how black they may seem they will ultimately come to no more than passing clouds in front of the endless azure skies and radiant sparkling sunbeams that glitter, endlessly before me, always there, above whatever gloom I might be inflicting upon myself, always, ungrudgingly and unfailingly patient in waiting for me, without judgement, to be finally grownup enough and ready to dive into them, bringing with me as many people as I can carry. And I nearly cried there and then; but I’m English. So instead, I went into the shrine room, I gathered my mat and cushions, I settled myself down and I contented myself with silently, deliciously, allowing the tears to roll down my cheeks all the way through the lunchtime drop in meditation class, to the extent where I began to believe I might spend the rest of the afternoon with wrinkled cheeks, as if I’d been face down in the bath for an hour.

I have so much potential. So much to do. So much I can achieve. These things won’t come, either, in the format of all the other things I’ve ever used to judge myself or assess my worth. These things won’t be expressed by graded certificates, resigned to battered folders. They won’t be tallied by marathon medals in a dusty box. They won’t be checked by piled sketchbooks or exhibited paintings or published writings. They can’t be described at all by collected things, finally doing no more than keeping each other company in my uncle’s loft. Nor will they be digital manifestations. They won’t be collected selfies in a social media album that seem to reflect the person I think other people think I should be trying to be. They won’t be blog posts or articles or poems online. They won’t be aggregated bullet points on an evolving CV and they certainly won’t be piled up credit tokens in a virtual bank account, not mine and not even a charity’s. The contribution I have the ability to make to the world, the changes I will go on to make cannot be counted or collected at all. They will be as transient as a phantom smile flicked onto the lips of a miserable stranger when I recognise their humanity with a broad and honest grin in the street. They will be as deep but inexpressible as the aches eased by plumping my uncle’s cushions before he’s come back into the room and as non-existent as the symptoms deflected by preparing his medication for him before he’s woken up. They will be as tiny, yet as unstoppable as a seed of self-belief sown in the mind of a generationally oppressed teenager, that will push up with the raw natural energy of a wild flower through a brittle tarmac of sedimentary hate. They will be as paper-thin as the subtle uplifting in mood of a troubled mind I hear, or connect with, or make a much needed cup of tea for (for we all know that sometimes a cup of tea is for the mind, not for the stomach). They will be as indistinct and as feral as my own failings and struggles, shared with an intention of marginally lightening the burden of another’s perceived inadequacy, despite risking my own vulnerability. These things I achieve will be tiny. They will be weak. They will be unremarkable, insignificant, almost pointless. But they will drip, drip, drip in to the world in a relentless trickle of positivity. They will create the softest of secret, silent ripples and you won’t even notice they are there. But you can feel it now, can’t you? Gently, lifting and stirring you? Because these ripples will swell in to waves. It’s in you too. And these waves, between us will form an encroaching tide, a rush, a swell, an unarguable uprising. As yielding as water. As unstoppable as a tsunami. And we will win. This love will save the world.

And then the bell rang for the end of the meditation, and I thought, ‘I’m home. Where next?’

Three weeks later, and I finally engineered the time and the train fare to head back into London for a meeting at the Triratna centre in Bethnal Green. I stepped in to London Buddhist Centre courtyard and the familiarity, the placid, unchanged calm, triggered a genuine flood of raw emotion, finally given a point of release. Here, my brain eventually threw caution to the wind and necked shot after hard core shot of relief, gratitude, compassion and love until I was quite drunk in an aura of fuzzy, warm, positive emotion. As I removed my shoes and hung up my coat, this vague yet forceful release distilled itself into an awareness of where I am coming from and what I had just done. An acknowledgement of the events I had been a part of and the commitments I have made, all set against the backdrop of the sheer unadulterated brightness and joy of what my future holds, despite the difficulties I still work with, despite the days I find hard. I really knew then that no matter how black they may seem they will ultimately come to no more than passing clouds in front of the endless azure skies and radiant sparkling sunbeams that glitter, endlessly before me, always there, above whatever gloom I might be inflicting upon myself, always, ungrudgingly and unfailingly patient in waiting for me, without judgement, to be finally grownup enough and ready to dive into them, bringing with me as many people as I can carry. And I nearly cried there and then; but I’m English. So instead, I went into the shrine room, I gathered my mat and cushions, I settled myself down and I contented myself with silently, deliciously, allowing the tears to roll down my cheeks all the way through the lunchtime drop in meditation class, to the extent where I began to believe I might spend the rest of the afternoon with wrinkled cheeks, as if I’d been face down in the bath for an hour.

I have so much potential. So much to do. So much I can achieve. These things won’t come, either, in the format of all the other things I’ve ever used to judge myself or assess my worth. These things won’t be expressed by graded certificates, resigned to battered folders. They won’t be tallied by marathon medals in a dusty box. They won’t be checked by piled sketchbooks or exhibited paintings or published writings. They can’t be described at all by collected things, finally doing no more than keeping each other company in my uncle’s loft. Nor will they be digital manifestations. They won’t be collected selfies in a social media album that seem to reflect the person I think other people think I should be trying to be. They won’t be blog posts or articles or poems online. They won’t be aggregated bullet points on an evolving CV and they certainly won’t be piled up credit tokens in a virtual bank account, not mine and not even a charity’s. The contribution I have the ability to make to the world, the changes I will go on to make cannot be counted or collected at all. They will be as transient as a phantom smile flicked onto the lips of a miserable stranger when I recognise their humanity with a broad and honest grin in the street. They will be as deep but inexpressible as the aches eased by plumping my uncle’s cushions before he’s come back into the room and as non-existent as the symptoms deflected by preparing his medication for him before he’s woken up. They will be as tiny, yet as unstoppable as a seed of self-belief sown in the mind of a generationally oppressed teenager, that will push up with the raw natural energy of a wild flower through a brittle tarmac of sedimentary hate. They will be as paper-thin as the subtle uplifting in mood of a troubled mind I hear, or connect with, or make a much needed cup of tea for (for we all know that sometimes a cup of tea is for the mind, not for the stomach). They will be as indistinct and as feral as my own failings and struggles, shared with an intention of marginally lightening the burden of another’s perceived inadequacy, despite risking my own vulnerability. These things I achieve will be tiny. They will be weak. They will be unremarkable, insignificant, almost pointless. But they will drip, drip, drip in to the world in a relentless trickle of positivity. They will create the softest of secret, silent ripples and you won’t even notice they are there. But you can feel it now, can’t you? Gently, lifting and stirring you? Because these ripples will swell in to waves. It’s in you too. And these waves, between us will form an encroaching tide, a rush, a swell, an unarguable uprising. As yielding as water. As unstoppable as a tsunami. And we will win. This love will save the world.

And then the bell rang for the end of the meditation, and I thought, ‘I’m home. Where next?’

RSS Feed

RSS Feed