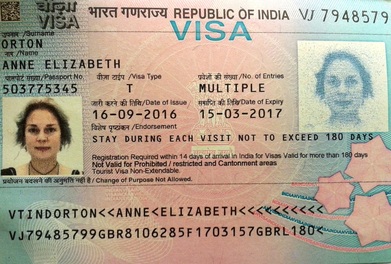

When I arrived in India, I quickly realised that I was going to meet many people whose stories deserved telling. This was perhaps not because they were particularly unusual, but because they would demonstrate a kind of tenacious determination that I feel is becoming eroded in the west, where many people have learned to take so much more for granted and where relative comforts have, in many cases, made it easier to accept the status quo. I’m not sure this has always been the case though, and I think we’d do well to be reminded of our potential for self-improvement and social development. I didn’t get to write as many of these stories as I’d hoped; I have learned it takes a good deal of time to research the facts, let alone write such a biography well enough to do it justice, especially when your subject has a busy schedule. That’s before you’ve accepted the fact that everything just seems to take longer in India, too! However, there was one story that I was determined not to leave without writing. This is Neha, who is also the first person whose story I realised really needed to be shared. Neha is also one of the first people connected with Aryaloka that I met when she visited the UK in June of 2016 as part of a trip to Europe, having been commissioned to film a documentary about how people from the Romany Gypsy community in Hungary have found inspiration and strength in the work of Dr Ambedkar. This in itself is indicative of the kind of woman she is; you have to be a pretty remarkable person to get such an opportunity when you’ve started life in the conditions she experienced.

| Neha is the youngest of three sisters but also has a younger brother. This is significant and the family stops here for a reason. As with many traditional Indian families, her father, if not her mother, was waiting for a boy. What might in other circumstances have been a joyous occasion therefore lacked celebration, in fact ‘Papa’ was so disappointed to have yet another daughter that he became angry with her ‘Mama’ and refused to even see Neha for a month after her birth, professing hate for the new arrival. It’s of no surprise that Neha goes on to reflect on her childhood as ‘not very happy’. Despite the controversy of her gender, she says she did feel loved at home, though I personally think this is little more |

than a testament to the strength of her mother, a generous and kind lady who I have met on several occasions. Her family could not afford treats or gifts and this in itself caused, and was caused by, a good deal of sorrow. ‘A normal child is playing and joyous’ Neha tells me, describing an idea she has of what a young life should be, not wanting for things such as chocolate and toys, ‘our family was not like that’. The sorry reason for the lack of funds will be well known to many. Until the age of 11, Neha’s Papa was heavy drinker. He was regularly home late and drunk, beating her Mama. He was earning, as he still is, as a rickshaw driver, but much of what he earned was spent on alcohol.

| At the end of 6th standard, Neha was ill at the time of her exams and she failed. Papa was very angry and decided she would spend the summer going to work with him as a punishment for poor studies. The cycle rickshaw he used was heavy and he was weakened by drinking. Neha’s job was, therefore, to walk behind the cart and push. This was not a passenger vehicle, as he now operates, but a goods service and unfortunately, his main occupation was delivering alcohol to bars, perhaps not how he developed an alcohol addiction in the first place, but certainly not helping him recover from it. Mama found work as a cleaner, going door to |

door and working in people’s homes. They all put in long hours in order to keep the family of six fed and clothed, despite their challenges. As I listen to Neha describe her upbringing, I can’t help but ask how she thinks the allotted social status of being from a Scheduled Caste (ex untouchable) family has impacted upon their lives. It’s a question I feel slightly awkward asking, and one I feel I have phrased in the clumsy terms of one who really doesn’t understand the hierarchical system they are questioning. It is perhaps too broad a question to be useful, too unsubtle to get to the heart of the matter. At least she does not seem offended by it, responding simply by saying that most of Indian society would dismiss the difficulties her family faced as the inevitable life of low caste status. A ‘put up and shut up’ attitude that does not empower people to develop either personally or socially. This is your lot. Accept it.

Though these circumstances put her at a disadvantage in many ways, Neha certainly learned to be a hard worker, particularly in school and she successfully passed 10th standard, moving on to 11th and 12th with no difficulty. At least she had no social distractions to keep her from her college studies; she was very shy and withdrawn, she recalls. She graduated from 12th class with good marks, but with no friends and few reasons to be happy. As something of a vote of confidence, she was advised by her teachers to train as a chartered accountant, which is considered to be a very good, and certainly well paid job. There is an entrance exam to continue studies in this field though, and while she could certainly have passed, she was not able to afford the course fees so she gave up on this idea and enrolled onto a Bachelor of Commerce degree instead.

Though these circumstances put her at a disadvantage in many ways, Neha certainly learned to be a hard worker, particularly in school and she successfully passed 10th standard, moving on to 11th and 12th with no difficulty. At least she had no social distractions to keep her from her college studies; she was very shy and withdrawn, she recalls. She graduated from 12th class with good marks, but with no friends and few reasons to be happy. As something of a vote of confidence, she was advised by her teachers to train as a chartered accountant, which is considered to be a very good, and certainly well paid job. There is an entrance exam to continue studies in this field though, and while she could certainly have passed, she was not able to afford the course fees so she gave up on this idea and enrolled onto a Bachelor of Commerce degree instead.

One day, a neighbour who knew she enjoyed drawing and painting, called on Neha for company while she enquired about a six month animation course. The course cost 15,000 rupees and her neighbour decided she wasn’t interested; but Neha certainly was! She applied and paid the 1000 rupee deposit with all the money she had and no idea where or when she'd get the rest. Knowing she may be forced to leave after the first month, she studied hungrily and learned fast, often being asked for help by her peers! This also encouraged her to become more social and after confiding in a friend on the course about her uncertain place on the course, she was helped to get a job working as a Photoshop operator in a photo studio. The director of the studio drove a hard bargain, asking why she deserved payment if she was inexperienced and unqualified. She explained her situation, that she only wanted the remaining 14,000 to continue the animation course, offering to work every day if needed. Her enthusiasm, if not yet her skills must have been impressive and so she secured the job and the security of finishing her course. During this time, she rose early every morning to help with household work, leaving at six every morning to attend the animation course before working in the photo studio. Her day also included continued study on the Bachelor of Commerce course as well as office work, and yet more study when she returned home not normally until after 9pm, finally ending her day around midnight. After a month at the studio, the manager was sufficiently impressed that he helped her get a scholarship on the animation course and began paying her an actual wage, which she put straight into supporting her family.

This was not just a time of development and personal transformation for Neha. After attending a one day retreat led by Subhuti at Nagaloka, at which he is reported to have had a bottle of wine conveniently stashed in a nearby bush, her papa stopped drinking. One of Neha’s domestic duties had been to prepare tobacco for her father, rolling it into betel leaves to make paan for chewing; but when he came home from the retreat that day, he did not want paan. After two days, he had stopped drinking and now, she tells me proudly, he doesn't even drink chai, taking only milk in the morning and water throughout the day. Neha and her family had thought they enjoyed the freedom of Papa being away for a day on the retreat but could never have guessed how their lives might change as a result of it; no more shouting, no more anger, no more violence.

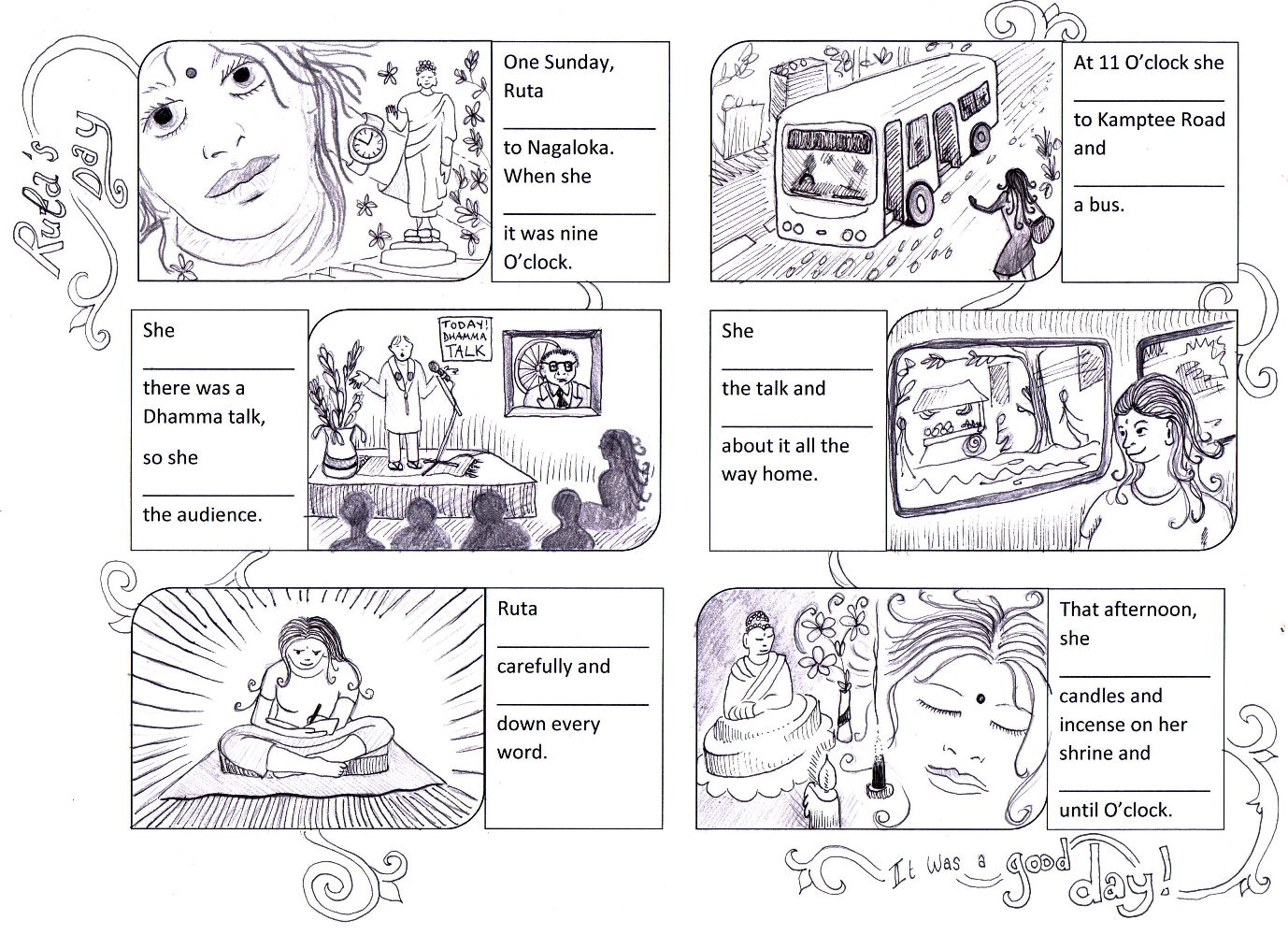

In 2007, as he continued to attend classes and events at Nagaloka, Papa met Aryaketu (director of Aryaloka) and heard him discussing various creative projects, including those involving animation; he didn’t waste much time in detailing his daughter’s experience and asking about opportunities for her. Aryaketu was looking for help making a comic about Buddhist teachings and so he offered her a chance to demonstrate her skills, agreeing that if her work was of a good standard she would be paid for it. Now she was involved in the Triratna community, Neha’s drive and potential was beginning to get noticed. By the time Shakyajata was organising and recruiting for the first batch of Young Indian Futures students, three different people, all order members, had separately recommended her, keen to support her progress if possible. As such, Neha became resident in the first community of young women, living and studying at the old building in Indora.

In 2007, as he continued to attend classes and events at Nagaloka, Papa met Aryaketu (director of Aryaloka) and heard him discussing various creative projects, including those involving animation; he didn’t waste much time in detailing his daughter’s experience and asking about opportunities for her. Aryaketu was looking for help making a comic about Buddhist teachings and so he offered her a chance to demonstrate her skills, agreeing that if her work was of a good standard she would be paid for it. Now she was involved in the Triratna community, Neha’s drive and potential was beginning to get noticed. By the time Shakyajata was organising and recruiting for the first batch of Young Indian Futures students, three different people, all order members, had separately recommended her, keen to support her progress if possible. As such, Neha became resident in the first community of young women, living and studying at the old building in Indora.

Neha at the family home with Mama and Papa

Neha at the family home with Mama and Papa She finished the course at Aryaloka, very happily in 2009, with as much success as one might expect, knowing a little of her determination. She learned English and new creative software such as Maya, also improving her skills in other programmes such as Photoshop. Here, she felt confident for the first time too and made friends with the other eight women in the community, a bigger social group than she had ever previously known. She felt free for the first time too, and even found the confidence to speak with boys, challenging her own preconceptions that they must necessarily be up to no good, realising through this interaction that they were just as human as she, and also capable of good things! Critically, she also learned about the Dhamma and deepened her practice of metta (loving kindness). As the outstanding student of the first cohort, she was invited back the next year for a paid opportunity, teaching animation to the second year of students.

Of course things weren’t always perfect and she recalls the challenge of being away from her family for the first time, at least, she considers, she was not located too far away, which made it easier to adjust and she felt mentally prepared. Making good friends in the community helped too, and though there were quarrels at times, she felt able to stay out of them and not get involved. English was also a challenge for her, though she recalls memories of learning with Shakyajata and fellow UK teacher, Priyadaka, with great affection. She remembers creating a rangoli welcome for Shakyajata and when she finally arrived, such had been the depth of their correspondence by email that she did not feel it was the first time they had met. She vividly describes their first meeting, an emotional occasion where the tears flowed. She laughs at the memory; ‘that time, I am mad! I don’t know why!’ One thing she’s quite clear on though, is the crucial role that the opportunity at Aryaloka played in her development and current life. ‘If I didn’t study there, I wouldn’t be here now’ she states firmly. She didn’t leap straight into employment beyond Aryaloka; however and still faced difficulties turning her knowledge and skills into an income. She travelled as far as Pune, Deli and Mumbai for interviews, with mixed results. For some vacancies, she was still considered too inexperienced, for some, she achieved successful offers, yet her family would not allow her to live alone and so far away. Such is the disadvantage of girls in India, even those with clear talents and ambitions.

| By this time, Papa had not just allowed his discovery of Buddhism to improve his own life, he’d shared it with his whole family, who were now all practicing. Neha didn’t take long to fully embrace the opportunity to become more involved in the Dhamma either and became a Mitra of the Triratna order in 2010. She requested ordination in 2016. In 2011, her hard work finally paid off. She heard from her brother in law of a vacancy for a graphic designer at Lord Buddha TV, an alternative news channel based in Nagpur that broadcasts across the whole of India. After taking her show reel to interview, she was offered the job, a role she still more than fills, frequently spilling over into a myriad of peripheral duties with her multiple talents. It’s hard to imagine someone more dedicated to their employment, especially when the small organisation does not always have a smooth cash flow to enable timely payment of salaries. This is more than a job to Neha though; it’s not just an opportunity to engage in her creative passions either. Far more importantly than that, it is a way of helping to spread the word of the Dhamma and help others find ways to ease their own suffering. After all, such teachings affected a great deal of positive change in her own life and to share this potential is a key motivator for her. |

Her success in employment is also something she attributes to her time at Aryaloka. ‘I met Triratna, I learned about Buddha and Dr Ambedkar’, she says, learning that she feels she wouldn’t have got at any other institution. She does not believe she would be working at LBTV either, does not feel she would have found this opportunity to combine her Dhamma practice and her practical skills. In fact, she believes even the longevity of her job (she has seen many other members of staff come and go) is thanks to the depth of her practice and passion, which she would not have got from any other college. ‘I wouldn't have been able to afford it anyway’ she reflects.

Her time at Aryaloka has positively affected those around her too. After she began teaching and earning an income, she was able to support them to live much more comfortably. Her commitment to practice has also helped, feeding into and strengthening that of the whole family.

| Thinking back to our conversation as a write this, a snatched hour round the back of the stupa at Bordheran during a busy schedule filming the talks by Subhuti at the NNBY 10th Annual Convention, I realise that I have, in some ways set myself an impossible task. I can’t write Neha’s story yet, for despite the rich material in her first two decades, her story is far from complete, a fact she is all too aware of herself; this is not a fairy tale ending. ‘Is there anything else you think I should mention?’ I ask, half exhausted already from recording the details of so many trials and tribulations. ‘Yes!’ she responds, ‘My struggle is not finished!’ Every day at work is challenging, with more tasks than she can complete. She’s working on big stories too, broadcasting the talks and activities of some of the most senior order members, so there’s a lot of pressure to do so successfully, pressure that she doesn’t always even get paid for, when a key advertising client has not paid their fees, or the tiny channel has simply run out of cash. She’s had problems with colleagues as well, and recently encountered difficulties with bullying and blame, causing her to return home in tears every nights for a long spell. Her mum supported her through these problems though, and with this help she found the strength to stick it out, not reacting to or fuelling such unpleasant behaviour. Her skills and good will have also been stretched professionally; she was originally employed as an animator but when her manager left after just one month, her future was uncertain. At this time, she only knew how to work in 2D and animation software but the channel director liked her work and asked her to stay on in a different role, as an editor. For this, she taught herself how to work in entirely new editing software because no one else at the company would teach her. It was a similar story when she was invited to run her own programme. |

Colleagues behaved angrily and with jealousy when she achieved recognition for her work and so she had to learn a substantial set of new skills in filming; suddenly finding herself in the deep end with no camera man willing to work with her, presenting the programmes herself too, despite being very shy and having to learn all this completely on the go.

There’s another reason her story is not yet finished too; in fact, she has just started yet another new chapter as a newlywed, to Maitri, also a Mitra who has requested ordination and who works running a shop and restaurant as enterprises offering services to visitors at Nagaloka. Maitri is originally from Arunachal Pradesh, a northern state of India, with different customs, languages,

There’s another reason her story is not yet finished too; in fact, she has just started yet another new chapter as a newlywed, to Maitri, also a Mitra who has requested ordination and who works running a shop and restaurant as enterprises offering services to visitors at Nagaloka. Maitri is originally from Arunachal Pradesh, a northern state of India, with different customs, languages,

| | lifestyles and cultures. This in itself has been something of an issue for the couple; interstate marriages are not common and it took some time for Neha to ease the concerns of her family and achieve their blessings. Not that I suspect it would have stopped her if they’d maintained their disapproval. Aware of the imminent wedding, and as a somewhat excited guest, I was pleased for the opportunity to grill Neha on a happier issue; how did you meet? How do you think your life will be different after the wedding? What are your plans for your future as a couple? At this, she wrinkles her nose and asks ‘It is important?’ She tells me, after a joke dismissal of the question, that whatever happens, she plans to spend at least the next two years spreading the Dhamma through her work at LBTV. There will certainly be no children in the short term. In the long term, who knows? She remains uncommitted beyond her drive to become ordained, and this is something she feels they will be working for together, as Dhamma practitioners. ‘Maitri tells me we will be a team’ she says, ‘there will not be “your work” and “my work” in the home; we both have jobs, we will share the house work.’ There were other concerns too, of course; any young person about to enter into a lifetime commitment may be expected to feel somewhat anxious about such things and, I realised, when talking as a friend, not as an interviewer, that what from a Western perspective is a distinct lack of relationship experience was adding to these worries. I found that particular conversation very difficult at times and really got the sense that though Neha was indeed happy with the idea of getting married to Maitri, this was perhaps still in the context of feeling that she didn’t have much choice about whether or not she got married at all. ‘It’s not too late!’ I felt like saying, ‘run away with me!’ but knowing that would not be helpful, I contented myself with simply listening to her concerns and making it clear that I was willing to continue to do so at any time. If I can trust anyone to have made the right choice for themselves, I feel sure it’s Neha. She had at one time, she tells me, entertained the idea of leaving India entirely and becoming a nun, in order to fully commit to her practice and avoid marriage entirely. This, she feels is a more sensible and balanced approach that will allow her to stay connected with her family and probably to do more meaningful Dhamma work. |

| Any fears I, or indeed she may have had, have happily melted since the wedding and Maitri’s promise at least with regards to housework certainly seems to stand true; the wedding was in January, and I received an invitation to dinner shortly after the couple returned from some time away with Neha’s new family. Sure enough, alongside Neha in the kitchen, Maitri was chopping, cooking and washing up too. We had a fine meal, with Maharashtrian specialties cooked up by Neha, (including her first, very successful, attempt at pakora!) and some home treats prepared by Maitri. They seemed happy and relaxed together too, a relief to me, with my cultural preconceptions about equality and gender roles in marriage. Neha is glowing, smiling, as busy as ever at work, but still capable of telling me that she is very happy. Not yet quite a fairy tale ending perhaps, but a very joyful pit stop if nothing else, and it’s certainly a union that’s blessed from the start. There are not many weddings, I think, to which Subhuti, a very busy and senior order member, would fly all the way from Pune and back in the same day to officiate. Neha is clear that she never would have believed it to be possible for her to be living as she does now. This isn’t a matter of luck though, it’s sheer hard work, raw belief and pure determination that has achieved it. Yes, certain opportunities have arisen for her, but none that would have occurred without her own drive and motivation to realise the fruits of them. ‘If you had a message, for people in the UK who might read your story, if they are Buddhist, or if they are not, what would it be?’ I ask as a concluding thought, unsure that I will be able to articulate her experiences well enough myself to communicate the lesson that I know so many could learn from her example. She looks a little taken back at a difficult question and is thoughtful for a moment. |

‘I face difficulties and challenges in my life’ she states, ‘but friendship is most important.’ People, she says, are all the same and we have the same feelings. ‘I know what it's like to be hurt, so I believe in not hurting others. Respect each other. Treat others as you want be treated.’ This, she believes, is what has got her through.

| I’ve met many people in India, many of them have told me impressive tales of triumph over adversity, many of them I now feel honoured to count among my friends. I am sure, too, that I shall return when possible, to continue what I’ve left and that I shall meet many of them again. I don’t think, however, that there is anyone else I’ve met in my time here in whom I recognise that spark of deeper connection, a truly common perspective on the world and of our places in it, the kind of friendship you have where you almost instinctively realise a complete trust that this person will be around for the rest of your life, regardless of the circumstances you find yourselves in or the distances between you. If I think hard about it, I can actually only say I’ve met 3 or maybe 4 other people in my entire life with whom I feel such a connection, who I would call my ‘best friends’ and funnily enough, they all live in completely different countries. |

As I near the end of my first stay in India, I think of all the people I am going to leave behind, all the people I shall miss. Strangely, Neha is not among them and I think it is due to the strength of the bond I feel with her that this is the case. I shan’t miss her because in every important way, she’ll still be with me. I’m not sure where, or when, Neha and I will next meet, but I do feel sure that while her story is not over, she is going to somehow play an continued and important part in mine.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed