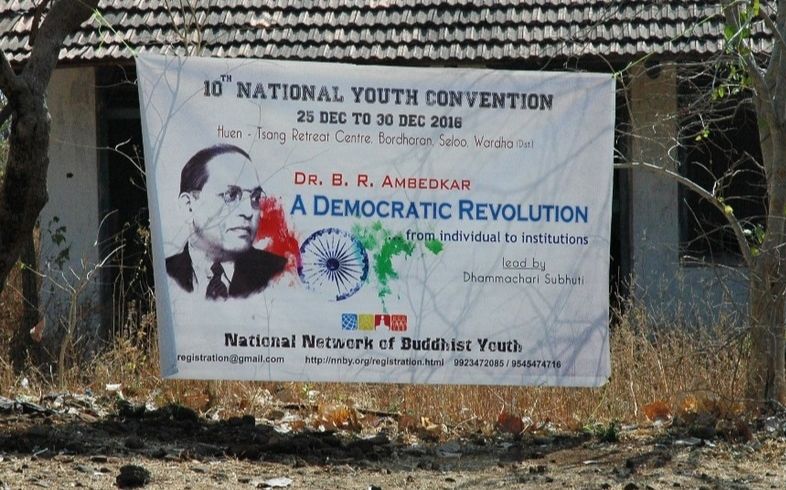

| I had first heard about the event, when Aryaketu had mentioned it in the car on our way to a semi solitary retreat in Bihali at the beginning of the month. We had initially hoped to take this retreat at Bordharan, which is much closer to Nagpur, but the centre had been fully booked. My interest was immediately piqued then, not only for the prospect of another opportunity to see Bordharan, but also because the retreat would be led by Subhuti, one of Triratna’s most senior Order Members and one of founder Sangharakshita’s foremost disciples. I had listened to recordings of Subhuti’s talks online and had read some of his work too, but even though he is president of the London Buddhist Centre, as he spends up to six months of every year on multiple trips working in India, the chance to attend not just one but a whole week of his talks in person seemed a very fine Christmas present indeed. At the very least, I’d be guaranteed to understand a percentage of the programme. Although a majority of it would be in Hindi, a common language for many of the young people who would be gathering from states all across India, Subhuti gives talks in English with an interpreter. Despite my initial enthusiasm, for a while it didn’t seem possible. Aryaketu seemed keen that I should attend, but various other people were not so sure it was a good idea; |

Still, I wasn’t sure how much I could jump up and down and demand to go, especially as I would be indirectly expecting my colleagues to take on all the teaching again, but when I received an invitation from my very good friend Neha; designer, camera woman, editor and all round amazing creative whirlwind at Lord Buddha TV, who would be filming at the event, my resolve to demonstrate that ‘where there’s a will there’s a way’ became manifest and so at 10:30 on Christmas morning I was honoured to take the front seat of a car bursting with people, luggage, camera equipment and a good deal of excited metta.

I had hoped that I might be able to assist Neha; I knew she’d have a very busy schedule and though my background isn’t in media directly, I can turn my hand to the photographic if required and learn pretty fast. This modest ambition hadn’t accounted for language barriers however, and though Neha’s English is better than basic, my Marathi, like my Hindi, is non-existent and it was obviously easier for her to simply do something than explain to me what needed doing. Her brother was also helping with a second camera so actually, she was fairly well covered and I contented myself with occasional ferrying of equipment to feel useful. As such, I quickly realised that following Neha round like a duckling follows mum, whilst reassuring, was not really helping either of us. After unloading into our luxuriously sardine-free room, shared with only five other Order members, organisers and Erica, (the only other white face at the event aside from Subhuti himself!), I left Neha to her work and began to absorb the reality of the situation into which I had voluntarily plunged for the next 6 days.

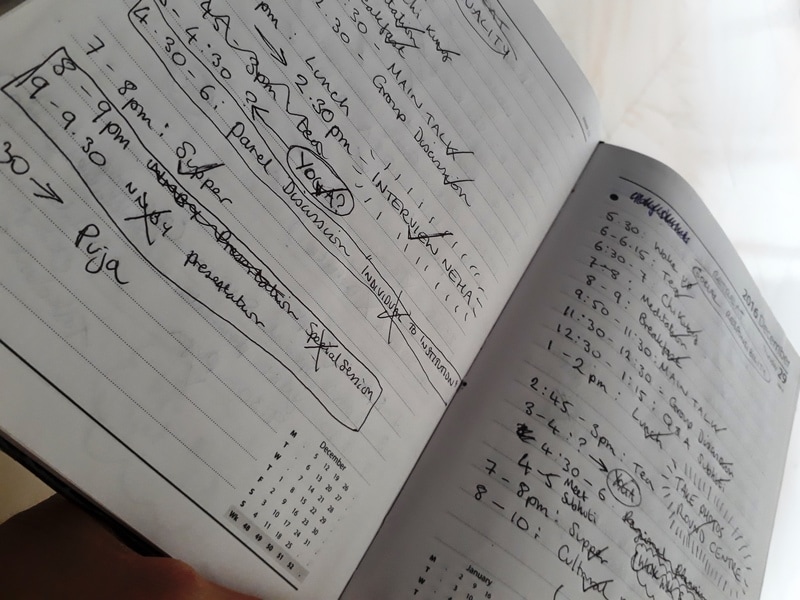

| My first act of settling in was to make a note of the programme for the days ahead in my diary, as listed on a printed programme I borrowed from Neha. Though subject to change, it gave me a good starting point. I also quickly realised exactly why the event was being referred to as a conference rather than a retreat! Each day started at 05:30, when we were encouraged to ‘wake up’. Tea would be served at 06:15, followed by half an hour of Chi Kung at 06:30. This preceded an hour of meditation at 07:00, with breakfast between 08:00 and 09:00. The day then really got going with the main talk (by Subhuti) at 10:00. Each day had a different, related topic; How to Think, Transformation, Equality, Social Responsibility and finally, Being an Activist, then after the 90 minute talk, we would split into discussion groups. Some days followed this with a ‘Q&A with Subhuti’ session planned before lunch at 13:00. 14:00 to 14:45 was generously scheduled as ‘rest’ before more chai and a series of ‘floating sessions’ at 15:00, which I soon learned meant somewhat impromptu study and/or discussion sessions. From 16:30 until 18:00 would be debates, panel discussions or seminars related to the theme of the day and after supper (served between 19:00 and 20:00), there were talks, presentations or celebratory activities leading up to the close with a puja at 21:30. The schedule kindly timetabled ‘sleep’ at 22:00. I began to see that the week would slip by very fast indeed. |

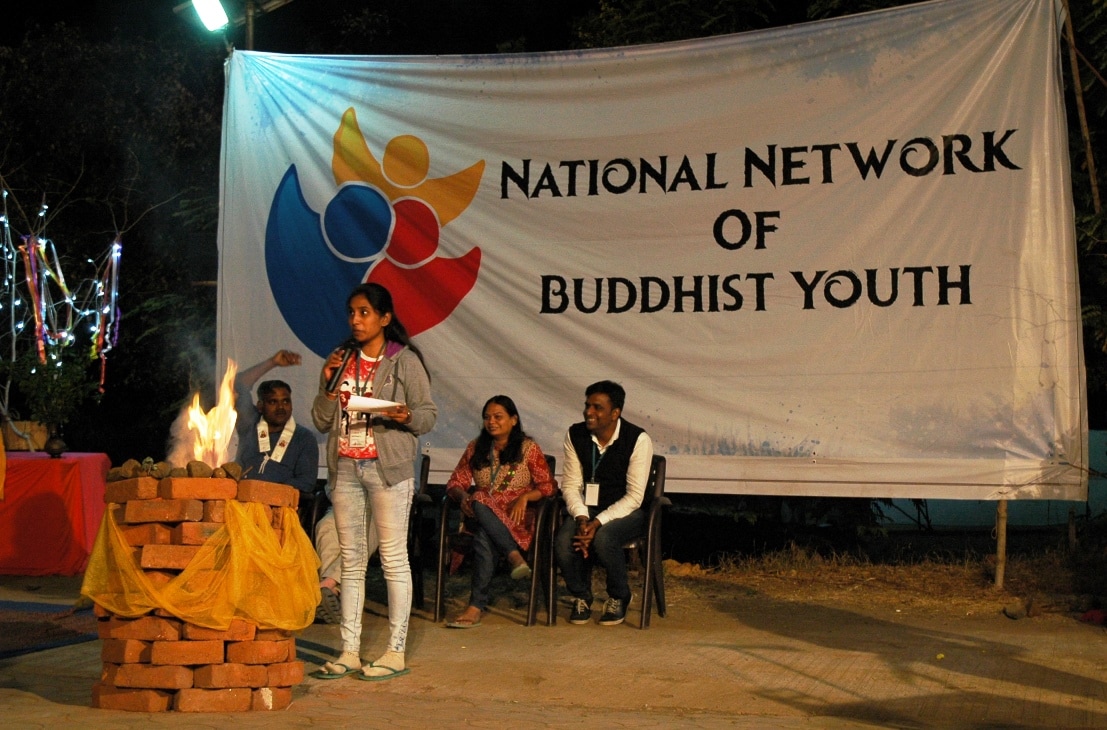

| It was as well I rested; the opening ceremony was a high energy affair with a re-enactment of one of Dr Ambedkar’s most famous acts of civil and spiritual disobedience, which clearly stimulated the already excited crowd to even stronger resolve with regards to their purpose for the week. On December 25th 1927, Dr Ambedkar had publically burned a copy of the core Hindu text, the Manu Smriti. Subhuti explained that though this was often presented as an ancient script, it was in fact relatively modern and had been written by Brahmins (Hindu high caste community), containing within it the primary justification for caste discrimination in the Hindu religion. Burning this document was one of the first public steps Ambedkar took in renouncing the religion of his birth and the entrenched injustices that so many were subjected to in its name. I realised then that this was not ‘just’ an opportunity for young people to learn about Buddhism and meekly deepen their practice. Many of those attending this event would be children of Ambedkarites, social activists born and bred, possibly even descendants of those who were at the original mass conversion 60 years ago. Many, though not all, would be from Scheduled Caste backgrounds and if the flavour of the event (subtitled A Democratic Revolution; from Individual |

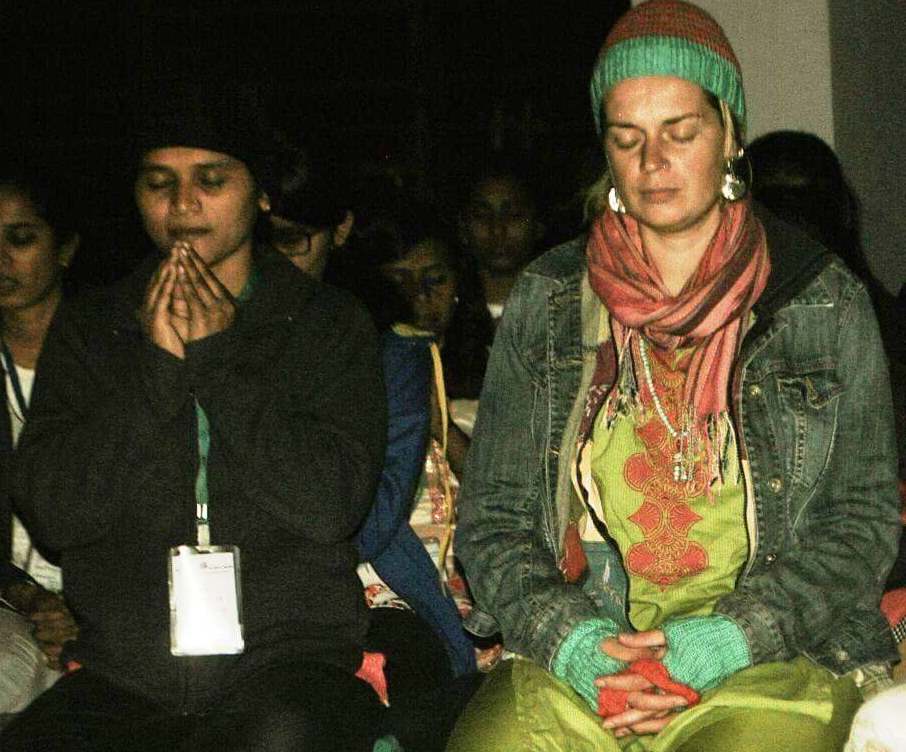

| So it was that I again found myself on a fast track integration process; once more a fish out of water socially, politically, culturally and spiritually. This was heightened by the anticipated number of very curious and excitable teenagers, many of whom had never seen a white person before and thought nothing of making comments such as ‘when I first saw you I thought you were an albino because we’ve got them in our village but actually it’s OK because now I know you’re a foreigner’ (read awed emphasis on that final word). I had enjoyed a surge of confidence since my post-Bihali spiritual rebirth experience (as discussed in my last update) but I now found myself reacquainted with a more withdrawn and introverted version of myself. I did not wish to appear unfriendly and wanted to be sure I was giving a positive first impression, where it was being taken, on behalf of modern Western people (no pressure there then), but I needed to remain equally true to myself and at the time, this was a self of study, observation and introspection. I skipped around the edges of multiple social interactions, like a pebble not yet committing to the lake and tried to politely take my leave as quickly as possible. After the first full day, I realised that participating in the afternoon events was probably not the best use of energy. As they were all in Hindi, I would understand only a tiny percentage of the material and so I was glad to carve some space for myself each afternoon while the ‘coast was clear’ for reading (I’d brought some texts), rest and yoga (I’d also brought my mat!). The daily highlight for me was without doubt the main talk by Subhuti and as I waited in the atmosphere of hushed excitement for the programme to begin on the first morning, I sensed I was not alone in this. I really felt myself to be at the ‘cutting edge’ not just of my own personal practice but of the work being done in the Triratna Buddhist Order; and at the front of the Dharma itself, as if we were at the driving edge of a weather front gradually sweeping across a landscape of change. |

| Following these main talks, we quickly gathered in our discussion groups and I was fortunate to have several people in mine who spoke some English, Prachi especially, who kindly took on the role of interpreting. Diksha, NNBY co-ordinator, and Raul facilitated the discussions and always made a point of trying to include me wherever possible. I wasn’t always able to completely follow the discussion and sensed that on occasion the translated content of what I had to contribute wasn’t entirely as substantial as the thoughts I’d tried to convey, but nevertheless, I really enjoyed the opportunity to engage with a smaller, more controlled group of convention participants. That we met over the course of the week helped too, as I could actually begin to develop a sense of individual personality in a sea of faces and deepen my friendship with them. |

| Meeting Shraddhavajri must be recorded as one of the high points of my week, and has furnished me with yet another inspirational female figure to add to my growing collection since becoming involved with Triratna. Living and working in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, she teaches Physical Education as well as running Dharma classes, youth groups and supporting the Ordination processes of six young women. At least that’s everything I can remember. I suspect that’s only about half of it. She vividly described a talk she’d recently given on gender equality, how shocked some of her teaching colleagues had been by it and how much negative feedback she’d received in the aftermath. She’s a couple of years younger than me but by Indian standards that’s apparently very old to be unmarried. Still, she’s holding off the constant social pressure, but for how much longer she’ll manage, I’m not sure. I’ve often refused to call myself a feminist because those I have encountered in the west who describe themselves as such seem more interested in female supremacy than real gender equality, but listening to her made me realise that in India, I have absolutely no hesitation whatsoever in planting myself very squarely in a proudly feminist camp. I only wish I knew how to support such a remarkable woman, who is to my mind ploughing on in a strikingly selfless and admirable fashion to blaze a much needed trail and set a firm example to the women around her that their future need not be dictated by a default assumption of gender typical roles. | Neha is another of these inspirational women with whom I consider myself very privileged to have become friends and though she was busy much of the time, we did manage to sneak some moments for conversation, which further strengthened our spiritual and social bond. As well as discussing her feelings in the run up to her own wedding, a conversation I found very difficult at times, she kindly gave me a good chunk of her afternoon one day to tell me her story. Having written the life stories of Saccadhamma and Sheetal, I felt it was very important to share Neha’s. Not only is hers another tale of overcoming significant disadvantage, as an alumni of Aryaloka, it also details just how transformational the opportunities offered at the education centre can be. I knew it would be a good story but even I didn’t expect some of the details and I’m looking forward to sharing it as soon as I get a chance in the coming weeks. As a dedicated member of the Lord Buddha TV team, she is often behind the microphone when interviews are conducted but, she told me, I was the first person to ask her for an interview. That may be the case, I replied, and lucky me for getting there first, but I am absolutely sure I will not be the last. Such is Neha’s sparkling energy and selfless determination to spread the Dharma, she has found herself with the dubious privilege of being additionally stretched with the demands of being one of Subhuti’s most trusted assistants. And it is a privilege, but a hard earned one and though she clearly treasures his guidance and friendship with a great respect, this does mean she is often taking on a good deal of extra work. Without wanting to exploit her contacts or her good nature, I’d asked if it might be possible to arrange a meeting at his convenience; I didn’t want to assume special treatment, or that I’d be a priority in a busy schedule but it seemed like I would be missing an opportunity if I didn’t at least ask. True to form, she did what she could and told me that at 4pm on Thursday, I would be welcome to visit Subhuti for a chat. |

| It’s a strange thing to meet for the first time someone with whose appearance, speech and mannerisms one has become already familiar. Such had been the depth of my engagement with Subhuti’s talks that I almost felt as though we’d already conversed and Neha had described him as having such a kind nature that I didn’t feel at all uncomfortable taking myself up to the hut behind the Stupa where he was staying with Maitriveer, another Order Member Ratnakumar, and possibly one or two others. We were soon sitting on a small, basic, concrete veranda looking out on to a jungle scene of faded teak leaves and dry grasses. To describe the scene as a riot of beige might not be wildly inaccurate but seriously undermines it and perhaps tawny, amber, gold and sienna would all better describe the colours that shone out of the winter landscape in the warmth of the late afternoon sun. I’m not sure if it was because of this complimentary contrast or because they have this colour all of their own, but it particularly occurred to me that this otherwise visually unremarkable elderly gentleman to whom I had presented myself, had a pair of the most strikingly blue eyes I’ve ever seen. If the eyes really are the windows to the soul (though of course the existence of a fixed soul is not reality to a Buddhist) his radiated a wisdom housed in such clarity and depth, yet tempered with so delicate and light hearted a demeanour it that was hard not to feel an almost instantly affectionate respect for this person that I really only knew through very indirect means. Perhaps that he reminded me slightly of one of my uncles influenced this too. It’s probably no surprise that our conversation meandered its way into the realms of art (I think I sort of summarised how I’d ended up with Triratna and where I hoped to go next, but I’m sure we enjoyed all sorts of tangents along the way) and though I’m normally cautious not to bore people by forcing them to look at photos of my art on a first meeting, he did seem so genuinely interested that before I knew it I’d pulled out my tablet and broken my own social taboo. Time is famous for its elastic properties, especially when ones experience of it is particularly pleasant, and as well as thoroughly enjoying the depth of our conversation, I was also relishing the rare opportunity to speak so fluently and with such rich subtlety of vocabulary with a fellow Brit, so one might have expected time to have flown characteristically. This wasn’t how it seemed to go though, and when I was very courteously dismissed to make allowance for his next appointment (though ‘go away please, I need a rest’ would have been an equally acceptable termination) I was neither surprised not expecting to see that a full hour had passed. I could have happily carried on chatting indefinitely and know there would have been plenty more to discuss, yet I did not feel that I had had to wind up early, or that there were unexpressed thoughts left wanting. Perhaps that is how one experiences time when a genuine presence in the moment has been achieved and it’s true to say that such was my absorption that for not one second of that hour did my mind wander to mundane musing of things that had happened earlier in the day, or anticipation of events to come later. It was, then, with mild shock that I returned to my room to find my semi-written notes for the evening talk awaiting a swift conclusion. |

When I arrived at the arena where the stage was set for the evening, Neha was already setting up the camera. She looked exhausted as she fixed me squarely in the eye and clearly stated ‘I am only here for you!’ She’d hoped for an evening off as she had no commitment to film the cultural programme, but I’d persuaded her it couldn’t do any harm to record the performances, which even if she didn’t need footage from immediately, may come in handy for future projects. She’d considered this politely, clearly still with an eye to a night of relaxation, but then I’d gone and roundly scuppered any idea of an early night by being so inconsiderate as to actually go and give a speech! I was rather selfishly glad of her presence. Though it was potentially useful for whatever I ended up muttering about to be captured on film, I was really just very grateful of the moral support that her attendance implied. Of course, I knew I would be first up that evening but I was not expecting to be suddenly called to make offerings at the shrine on stage along with Subhuti, nor to be received myself with flowers and positioned on a seat next to him!

| If I’d not felt glad to have met him earlier that day for just about every other reason possible, I was suddenly very glad that this wasn’t our first introduction. I’d expected nothing of this part of the proceedings and as I was standing only slightly awkwardly to one side trying to work out how to participate appropriately while being urged to join in with the ritual, the gentleman acting as MC, calmly informed me that I had five minutes to speak. I equally calmly explained that I had planned for up to twenty. He didn’t seem to realise for one moment the conundrum that this presented me as he then pointed out that as I’d need to allow time for interpretation, what he meant really was that I had about two and a half. I decided to quit while I was ahead before my slot was reduced any further and placed incense on the shrine before participating in the ritual bowing and taking my seat. ‘Hello again’ is a much easier sentence when finding oneself suddenly on stage with someone than ‘nice to meet you’, and this did calm what would otherwise have been an increasingly fraught situation. ‘What are you talking about?’ Subhuti politely inquired as the audience settled. ‘Well,’ I began, ‘I was supposed to be discussing Why I am a Buddhist but I’ve just been told that the time I’d planned for has been reduced by about ninety percent.’ ‘You talk for as long as you like’ he replied, and so whilst I felt it would be a good idea to be as succinct as possible, I dispensed with an instinct to rush. I abandoned my A5 sheet of bullet points and instead began the monologue that I’d internally rehearsed in various parts throughout the preceding days. |

| I think I managed to get the bulk of what needed saying across by simply dispensing with my autobiography, which, whilst I’m sure my audience would have been delighted to hear, really wasn’t the most important point at all. Despite my slightly unprepared rambling, it seemed to go down well. I felt more confident when spontaneous applause erupted in response to one statement and when I returned to my seat next to Subhuti, he gently leant over and simply said ‘nice’, demonstrating perhaps more effectively than I had just done, exactly how much it’s possible to convey really very succinctly indeed. I relaxed as he then introduced the cultural night, explaining the importance of creativity and enjoyment, before our chairs were moved to the side of the stage and the stars of the night stepped up to take their places. I was relieved to be off the stage but still felt a little awkward to be sat with the lead team and was keen to reassert my position as ‘one of you’ by returning to my place in the audience as soon as possible, so I snuck back at an appropriate pause to enjoy all the performances with occasional interpretation from Neha and Raju. Raju later persuaded me to sing but I'm not posting the video of that bit. I’d been very reluctant at first as I felt I’d already had my share of the limelight and I’d earlier resisted invitations by my discussion group to read a poem. I realised though, as I sat there, that whilst I may feel uncomfortable because of it, like it or not I did represent something bigger than myself, I represented an international connection, and for young people who had perhaps never left their village before it was more important to utilise this than to try and demonstrate its lack of substance. I realised being seen to share in the event was more important than attempting to retain the illusion of dignity, so I agreed, and hacked my way through the same song I’d appeased the community girls with a couple of times; the only (appropriate) song I knew all the way through, a favourite from my teens and one that I realised as I sung it was strangely dharmic; Spaceman by 4 Non Blondes. I’m pretty sure I sang at least half of it flat but Hindi singing sounds like it’s in a different key or something to me anyway and no one seemed to mind, judging by the number of people who came up to me the following day and told me how ‘beautiful’ my singing was. Of course I suspect they’d have said that even if I’d pulled out my old party trick of gargling the Beatles ‘When I’m 64’ but I must have done something right. The most significant feedback I received; however, was from those who told me they’d felt moved, or touched by the talk, especially the comment ‘I didn’t realise someone from a different background, a foreigner, could feel the same way about things as me.’ Uh huh. There we go. Box ticked. Job done. | |

I’m not quite sure what form it will take yet, but I’m starting to see that bringing these qualities together, a desire to visit new places, an ability to connect with people from different backgrounds and to help them connect with one another as well as a deep wish to share dharmic practices, might be a really good foundation of skills that could be used in helping to realise Dr Ambedkar’s global vision for the future, within the framework of Sangharakshita’s teachings and the Triratna movement.

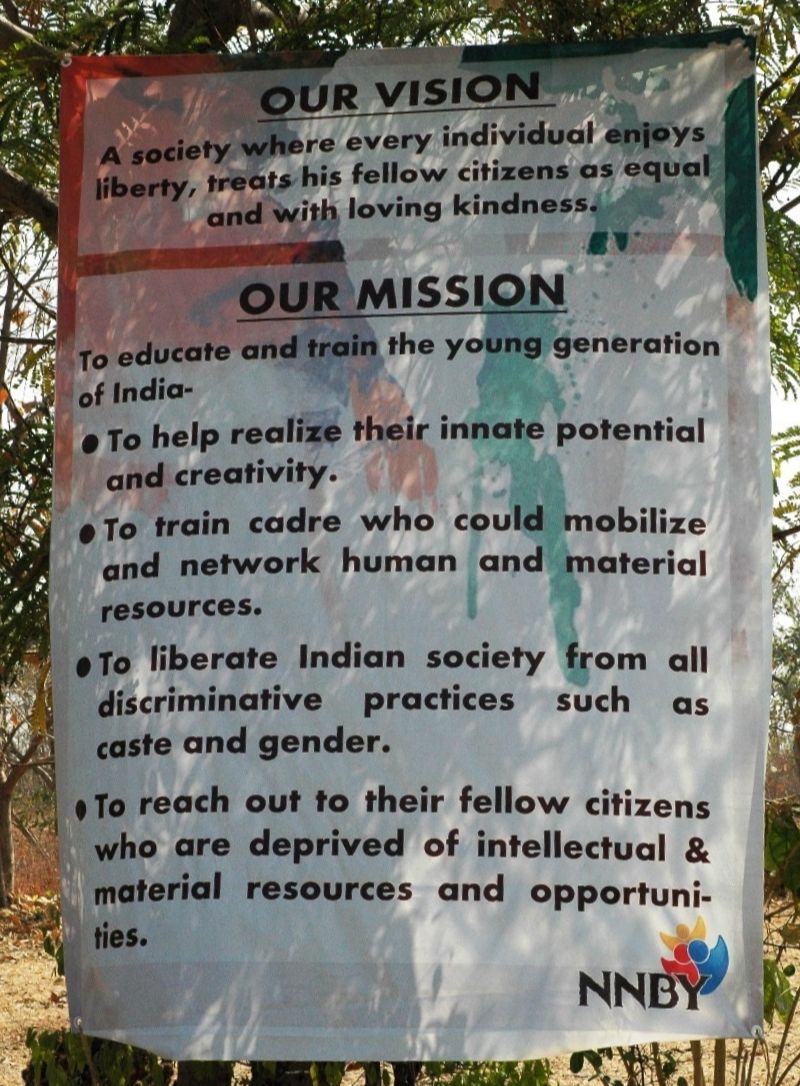

| That might all sound a bit grand. So much the better. I’m sure Subhuti hardly needs it from me, but I couldn’t have approved more of his closing lines. It’s important to have a long term goal but to get there, we must be skilled in applying the principles of Dharma to the situation around us; the Dharma is something to be lived. The Buddha is the ideal activist, Subhuti explained, and if you want to be an ideal activist you must become more and more like the Buddha. So then, after a week in the jungle with it, how can I describe the National Network of Buddhist Youth? In the first, most practical instance, it’s an organisation run by young people identifying as Buddhist, which seeks to make connections through common spiritual practice, spanning the different Indian states to achieve a goal of social equality and freedom from caste as inspired by the work of Dr Ambedkar. Really though, it’s so much more than that. It’s a vehicle that empowers young people, regardless of their background to realise the confidence and tools they need to reach their full potential. It enables its members to see not just through caste distinctions but beyond them, to recognise that they are united, not divided, by something far bigger. It provides opportunities for social development, for spiritual evolution and practical skills acquisition. It’s also the biggest bunch of friendly, energetic, dynamically excited young people I think I’ve ever met and I feel quite reassured, because if the future of the Dharma Revolution really does lie (at least partly) in their hands, then it’s definitely going places. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed