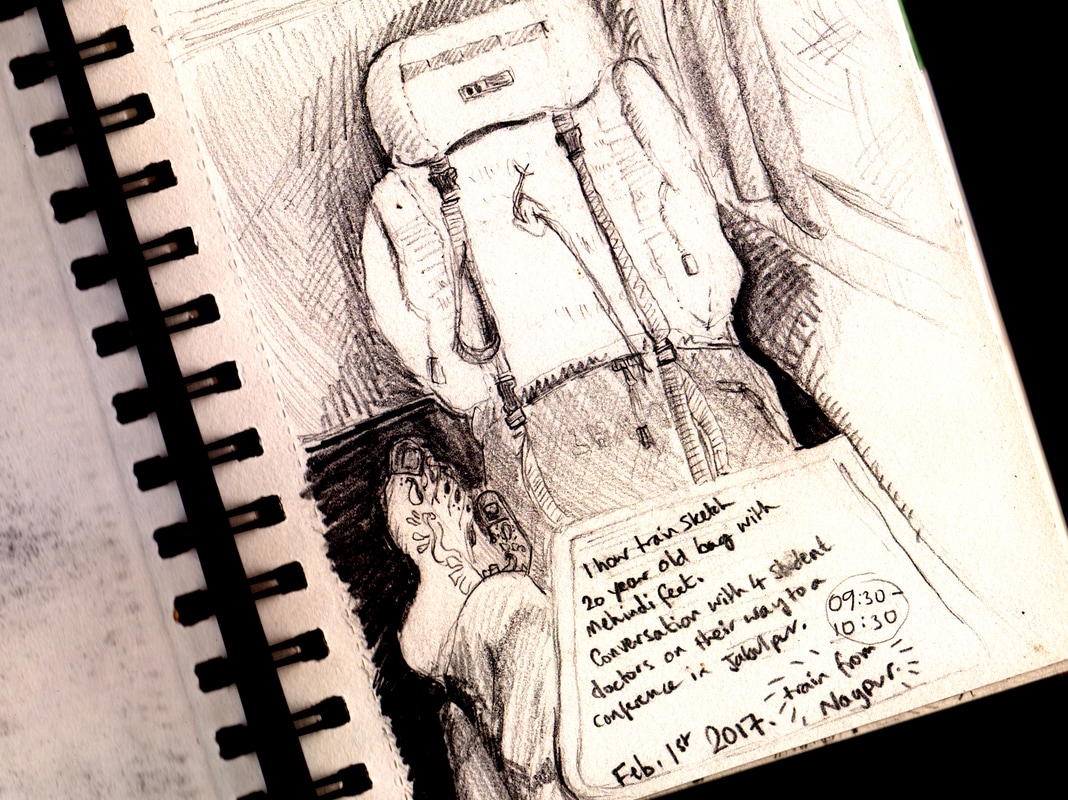

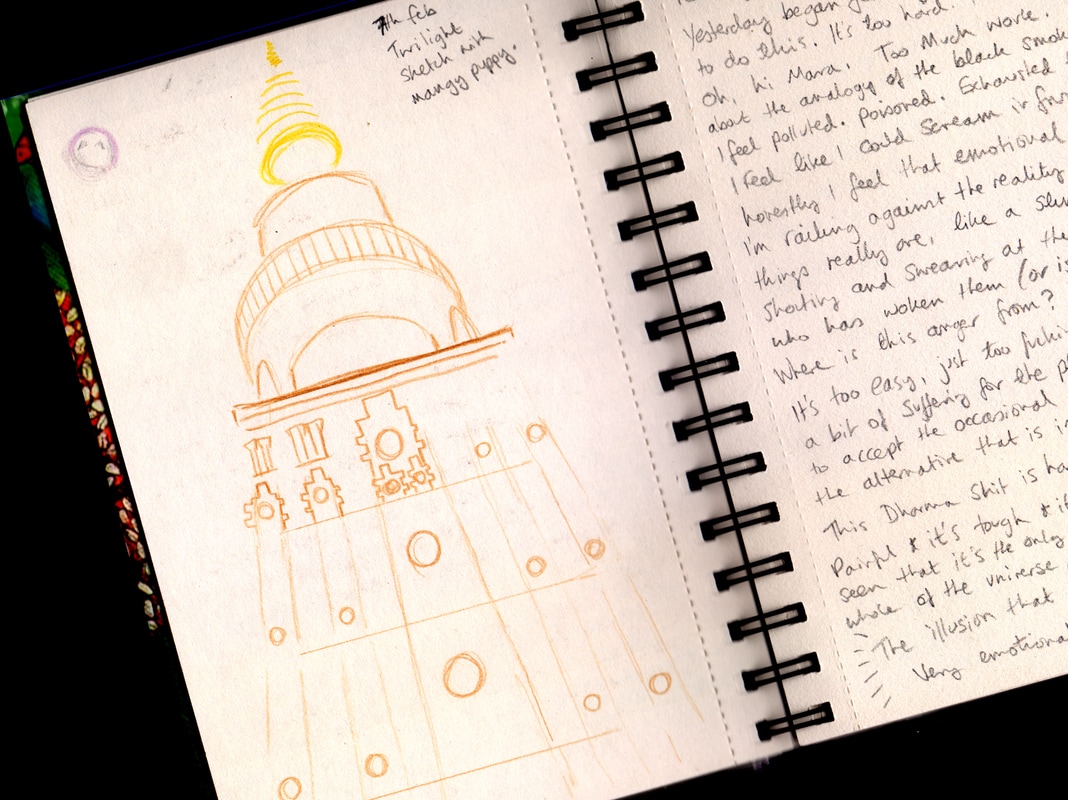

As I finally come to write this account of my two months distant visit to Bodhgaya, I realise it would be easy for me to let it become an exhaustive day-by-day diary of every experience and discovery, especially as I kept something of a journal in the form of daily notes and sketches. I’m aware that would probably not make for especially riveting reading though and it probably wouldn’t be particularly successful in communicating what I gained from it either. I shall try and avoid irrelevance but my reflections tend to take a path of their own so I can’t promise that. It’ll be what it is; an attitude I applied to the entire trip as I studiously avoided any assumptions or preconceptions in the days running up to my departure.

I should probably explain for those who don’t already know, that Bodhgaya is taken to be the location of the Buddha’s enlightenment. The Mahabodhi Temple is said to be built on the spot where Prince Siddhartha Gautama sat on a cushion of kusa grass to meditate beneath a peepal tree with such determination that he was able to resist the efforts of Mara (Buddhist equivalent of the Devil) to distract him from achieving Buddhahood. Of course, the peaks and troughs of 2500 years of history have not always been kind to Buddhism, less so its monuments but acceptance of impermanence is a key Buddhist teaching and it seems also largely accepted that the site is genuine, even if the temple has seen several restorations and the tree is only a grandchild of the original Ficus Religiosa or 'Bodhi Tree'. So, it’s a pretty important place if you’re Buddhist, or even if you’re simply interested in history, culture or Eastern religion. It’s a World Heritage Site and the principal place of pilgrimage for Buddhists around the world. When I first knew I was definitely coming to India to volunteer, I said to my colleagues, ‘of course my main purpose here is for work, but if it is at all possible I’d like to do just two other things; go on a retreat and visit Bodhgaya.’ I was, therefore, very grateful to my host, Aryaketu, for helping me to organise both these things and I had been looking forward to the trip since it was confirmed in November.

I should probably explain for those who don’t already know, that Bodhgaya is taken to be the location of the Buddha’s enlightenment. The Mahabodhi Temple is said to be built on the spot where Prince Siddhartha Gautama sat on a cushion of kusa grass to meditate beneath a peepal tree with such determination that he was able to resist the efforts of Mara (Buddhist equivalent of the Devil) to distract him from achieving Buddhahood. Of course, the peaks and troughs of 2500 years of history have not always been kind to Buddhism, less so its monuments but acceptance of impermanence is a key Buddhist teaching and it seems also largely accepted that the site is genuine, even if the temple has seen several restorations and the tree is only a grandchild of the original Ficus Religiosa or 'Bodhi Tree'. So, it’s a pretty important place if you’re Buddhist, or even if you’re simply interested in history, culture or Eastern religion. It’s a World Heritage Site and the principal place of pilgrimage for Buddhists around the world. When I first knew I was definitely coming to India to volunteer, I said to my colleagues, ‘of course my main purpose here is for work, but if it is at all possible I’d like to do just two other things; go on a retreat and visit Bodhgaya.’ I was, therefore, very grateful to my host, Aryaketu, for helping me to organise both these things and I had been looking forward to the trip since it was confirmed in November.

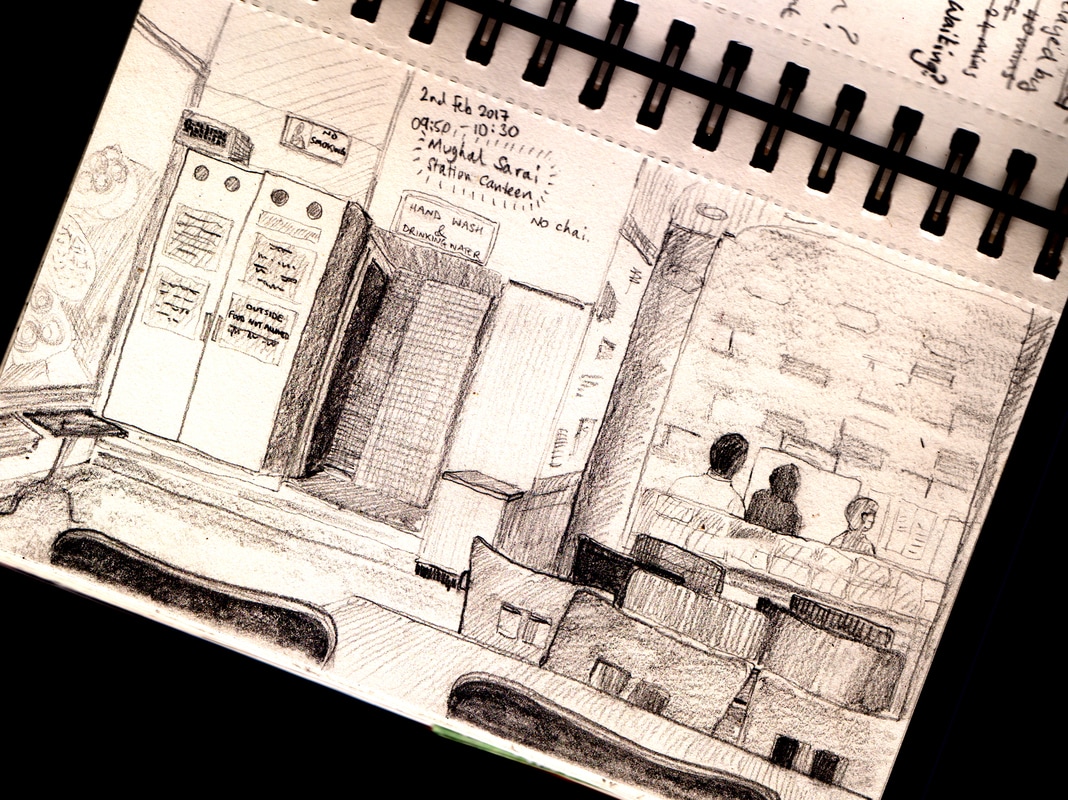

| Gaya is a good 24 hour train ride from Nagpur and Bodhgaya a few kilometres further still. My journey was always going to be especially lengthy as I had to change trains about 22 hours into my travel, with a five hour wait before the onward service from Mughal Sarai. I was initially quite pleased about this, since the likelihood for my train from Nagpur to be delayed was high and though I was fairly confident I’d be able to work out getting off one train and on to another, I wasn’t so sure I’d be able to negotiate a ticket transferral onto a new service if I missed the one I was supposed to catch. That sort of thing is tricky enough in England, let alone a country where you don’t speak the language. I needn’t have worried. The inbound train was only delayed by about an hour, giving me temporary cause for jubilation that I only had 4 hours to wait at the station, only until I realised that the ongoing train was also delayed by what eventually turned out to be another 7. If I’d known I’d have 11 hours to kill, I might have checked my bag at the luggage desk and gone for a wander but it was one of those situations where the delay grew by about an hour, every hour until I finally had no confidence that I really was on the right train at all. I only started getting a little fractious after about 9 hours. Up until that time I was strangely content to sit back and watch life come and go. I quite like stations, airports, service stations, any place of transience. So many lives and stories playing out before you; it’s almost better than the cinema. |

I arrived in Gaya long after dark with the plan of being collected by Buddhavajra, a Triratna order member I’d never met before. We’d not spoken either, until that afternoon, when he called to check the delay of my train. I hadn’t even told him. It was simply that inevitable. I reflected on how much anxiety that would once have caused me, compared with how little it bothered me now. I find it’s easy in life to focus only on the developments we still aim for, the improvements we still hope to make and to completely forget how far we’ve come. I was frustrated that I still had to get from Mughal Sarai to Gaya, forgetting I had already travelled all the way from Nagpur. Equally, I sometimes get irritated when I think of all the distance I’ve yet to travel personally without recognising the significant steps I’ve already made. Still, in this case I felt able to trust to the network of support that is the Triratna Sangha that someone from somewhere would collect me and convey me to safety and this indeed happened; I was soon whizzing though the dark night toward the Triratna land where a room had been arranged for me and a bed was waiting. As I lay in it, ‘only’ about 30 hours after leaving the family home in Bhilgaon, I realised how genuinely safe I felt. I also realised that the station snacks I’d succumbed to after running out of packed food at about hour 24 had been a bad idea. I’d already known that at the time, I think, but hunger and eventual frustration at the apparently endless spiral of delay had resulted in some unskilful decision making, the karma vipaka of which I was now certainly experiencing! Such is life.

I wasn’t too ill the next day to meet Buddhavajra and his family properly (I was staying in a room he had arranged for me with another family but I would be eating meals with him and his wife, Pritti) and he introduced me to a community of young men who live on the Triratna land to receive training in various subjects. The arrangement is very similar, though slightly less formal perhaps, to that which we have at Aryaloka and it felt quite comfortingly familiar to be again interacting with students, hearing their stories of village life, their aspirations and their experiences of learning about the Dhamma. I immediately offered some English taster classes during my stay, an idea that was readily accepted, though it didn’t end up being possible to organise in the end as the community members were soon engaged deeply in helping prepare for, and then run, an order retreat taking place at the centre. Still, the connections have been made, the conversations have been conducted and I think there is a lot of opportunity for the future here. The young people in the state of Bihar are even more disadvantaged than their Maharashtrian contemporaries and it would be a fruitful place to volunteer in future years.

I wasn’t too ill the next day to meet Buddhavajra and his family properly (I was staying in a room he had arranged for me with another family but I would be eating meals with him and his wife, Pritti) and he introduced me to a community of young men who live on the Triratna land to receive training in various subjects. The arrangement is very similar, though slightly less formal perhaps, to that which we have at Aryaloka and it felt quite comfortingly familiar to be again interacting with students, hearing their stories of village life, their aspirations and their experiences of learning about the Dhamma. I immediately offered some English taster classes during my stay, an idea that was readily accepted, though it didn’t end up being possible to organise in the end as the community members were soon engaged deeply in helping prepare for, and then run, an order retreat taking place at the centre. Still, the connections have been made, the conversations have been conducted and I think there is a lot of opportunity for the future here. The young people in the state of Bihar are even more disadvantaged than their Maharashtrian contemporaries and it would be a fruitful place to volunteer in future years.

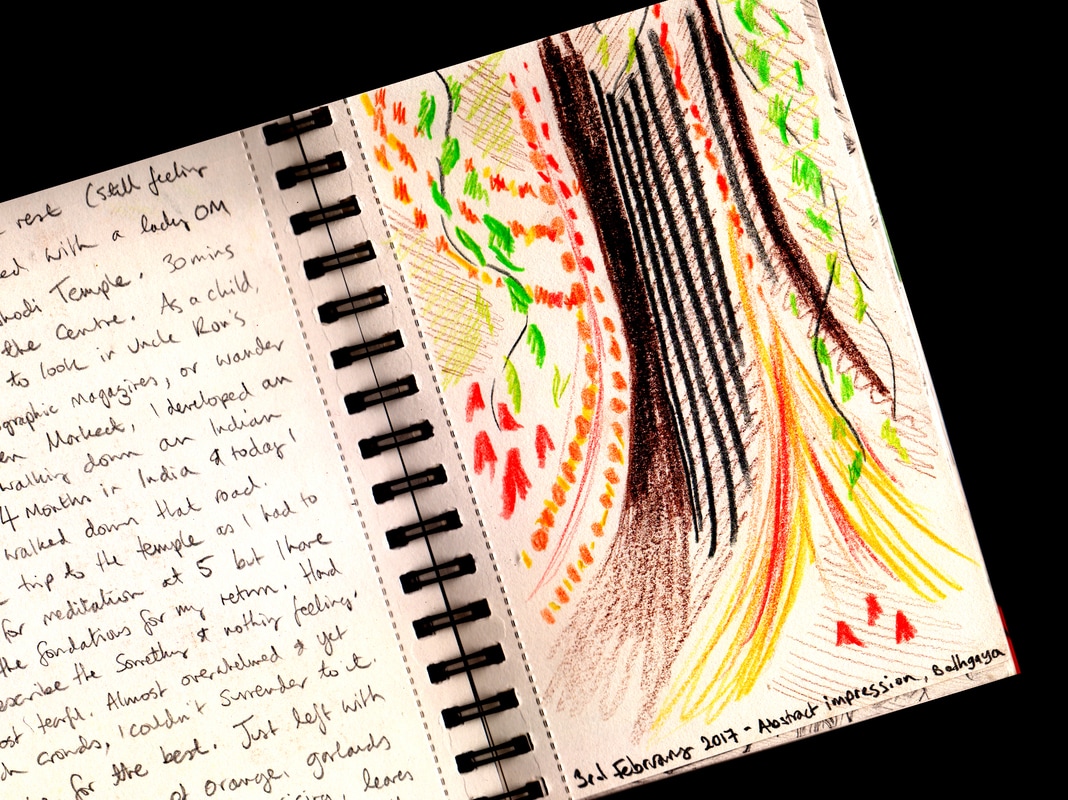

| My first visit to the Mahabodhi Temple ended up being a little rushed as I visited with one of the Dhammacharinis who had arrived a day early for the retreat, but I wanted to be back in time for evening meditation and checking in with the community students, so by the time we had walked there I had almost to turn around and come straight back. This mild pressure didn’t stop me having a strong experience though. As we walked up the busy, winding road to the temple, I got the sense that only just now was I in the India of my imagination. We always have something of an idea of what a place will be like before we arrive in it, built from pictures and stories we’ve seen or heard. The French philosopher Marc Augé discusses this in his essay Non-Places, introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (as well as a discussion of the aforementioned train stations and airports!). The ‘Non-India’ of my preconceptions had mostly been formed from long lazy afternoons as a child, scanning though back copies of my Uncle’s National Geographic subscription. This had given me a very rich visual impression, possibly augmented by shopping trips to ‘ethnic markets’ and an almost instinctive love of meals out in British curry houses! Of course, busy, dusty, urban Nagpur had resembled none of this but in Bodhgaya, the sounds, sights and smells lent a flicker of life to those flights of fancy that seemed now to be not so far from the truth after all. Stalls festooned with floating fabrics, trestle tables groaning with the weight of heaped miscellaneous trinkets, sacks spread out with an array of brightly coloured vegetables, fruit stalls with clouds of incense about them to deter the many flies, the occasional cow chewing surreptitiously on the stock. Monks in bright robes, rickshaw drivers in their jauntily personalised vehicles, auto or cycle, exhausted workers resting in the shade, grubby children playing in the street. That’s not to ignore the less savoury sights; poverty is rife and it’s impossible to avoid the fact that India does not appear to have any fixed solution to waste disposal. It is clear there is still a huge gulf between those who have and those who have not and the visual delights highlighted this; the brightest lights cast the darkest shadows. So it was perhaps because I was already experiencing a stirring sensory onslaught, or perhaps that I had not kept my hopes for the temple as neutral as I’d have liked, that upon getting my first glimpse of the ‘spire’ of the Mahabodhi Temple glinting, golden in the afternoon sun I felt really quite emotional. We had time just to go in, walk briefly round the complex and pay our respects at the shrine before I had to leave. I felt torn; I could easily have stayed, but I had a commitment to keep and I didn’t want the young people at the centre to get the impression I didn’t value their invitation so I resolved to myself that this was simply a reconnaissance mission and that I would return for a deeper engagement with the place in the morning. |

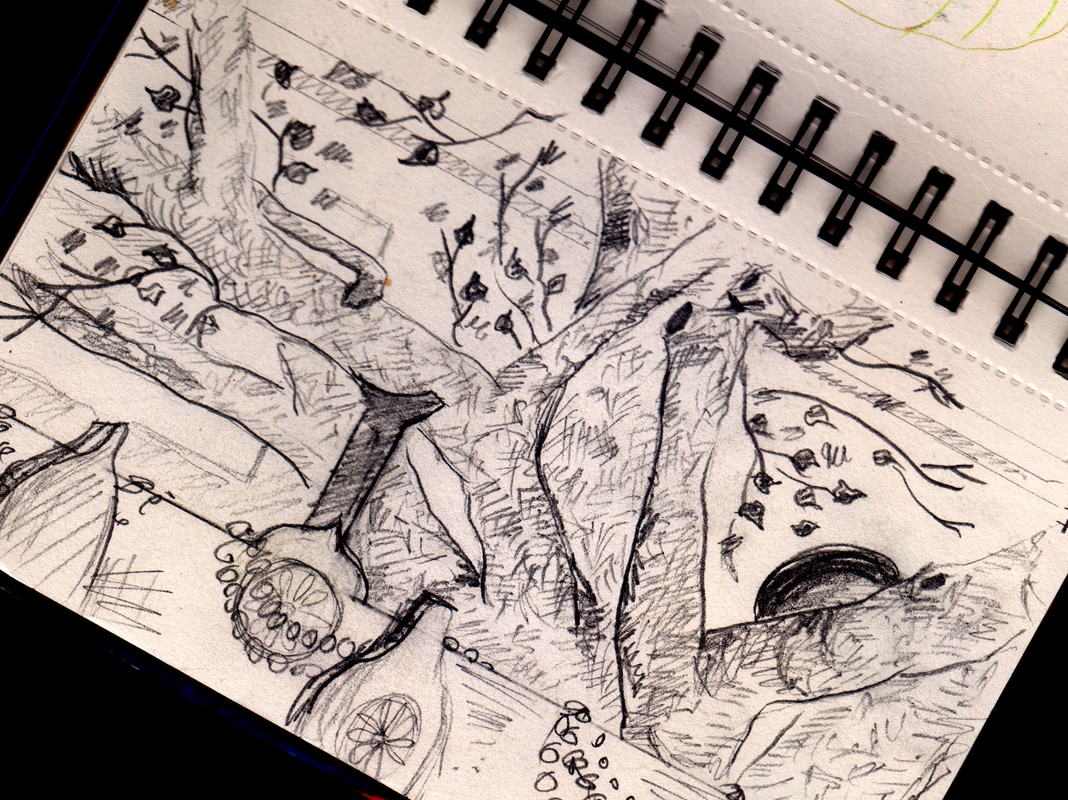

I returned the next day like an eager student on the first day of term, my bag packed with a sketchbook and pencils, my meditation cushion under my arm. I was determined to spend as much time there as possible, at least as long as my stomach could hold out to a late lunch, and I planned to sit, to meditate and to draw my little fingers off in recording all the impressions I could gather, to make notes on all the dharma I could possibly consume. I walked around the complex to find a good spot to settle and allowed myself to take in all the sights and sounds; draped garlands brightly hanging on every available monument, small floral offerings and cups of water placed in careful arrangements or simply huddled round edges where space was scarce. The shuffling of feet, the deep whirring of spinning prayer wheels, muttered mantras, clicking mala beads, glistening brows of those engaged in repeated prostrations on specially provided boards. This looked quite torturous but it must be a great upper body workout. I found a rare grassy patch and sat for some time to observe the comings and goings.

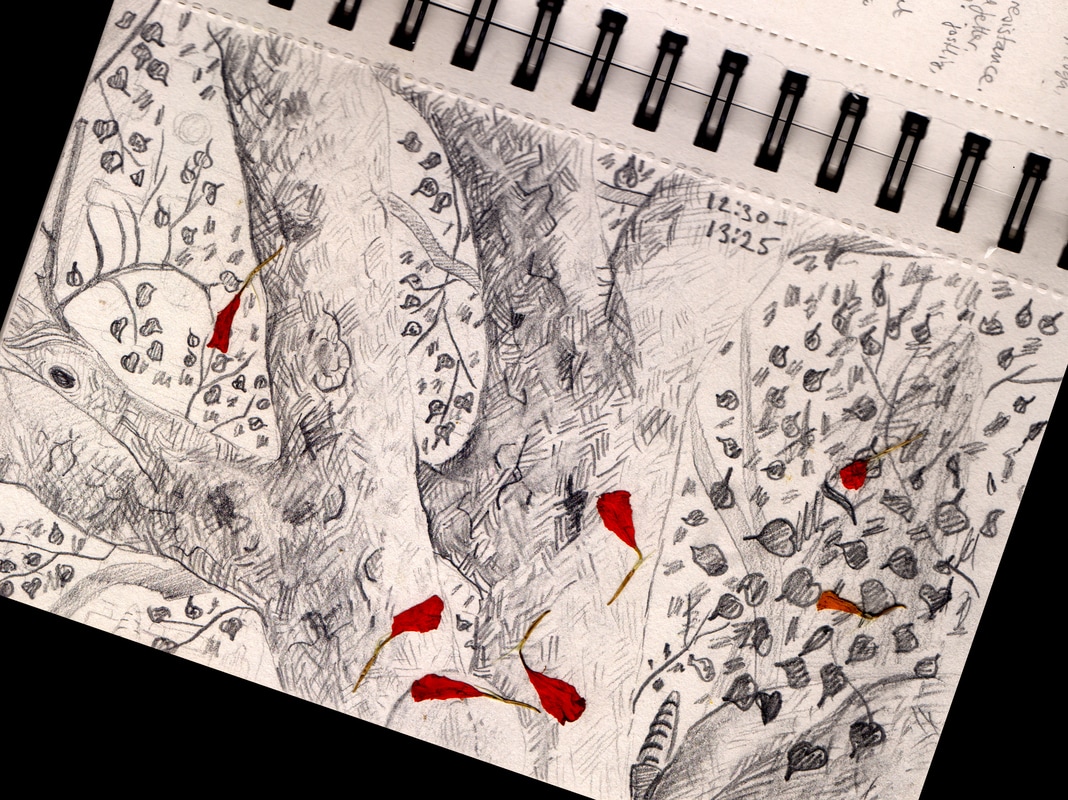

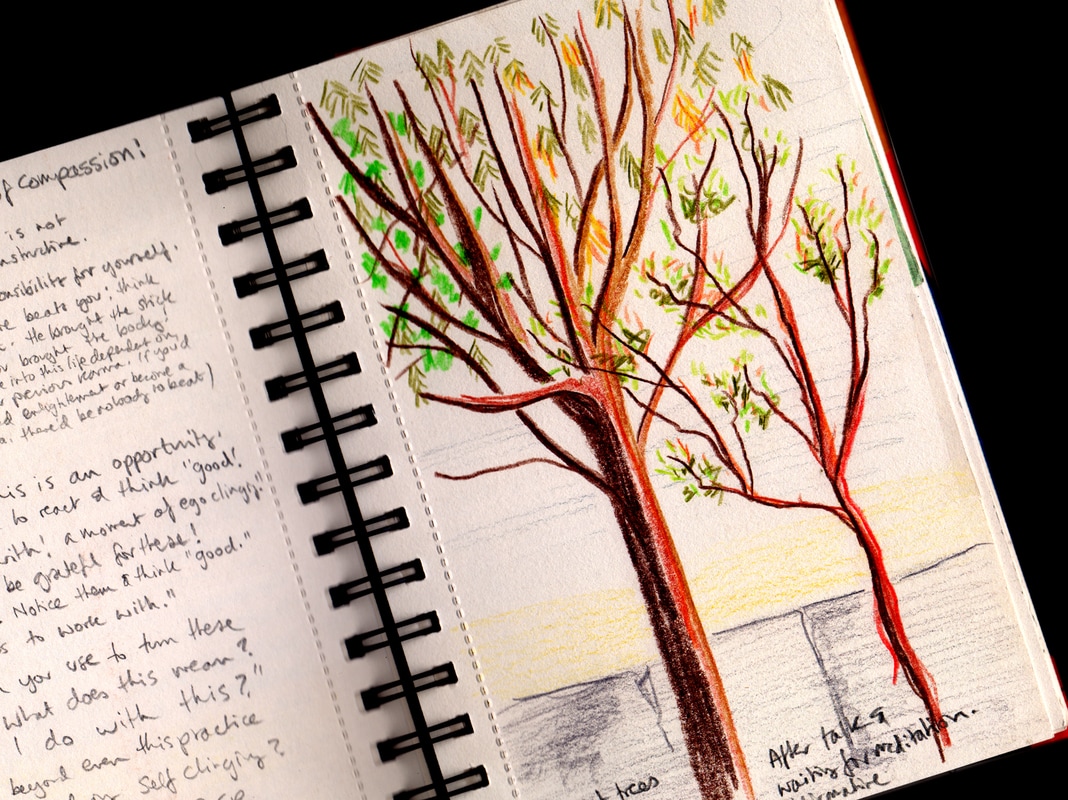

| The stray dogs and busy birds. The monks taking a break to eat from their tiffin boxes. The Chinese, the Indian, the Tibetan, the Western, the traditional, the new age, the tourists, the devotees. The cleaning staff, the shrine dressers, the security guards. I sat and waited for the inspiration to arise in me for a drawing. It didn’t come. I gently tested my mind to see if it was ripe for fruitful meditation. It responded with resistance. I made my way nearer to the central shrine and the Bodhi Tree and realised that what I was feeling was restless and irritable. This did not fall in line with the expectations I had told myself I should avoid but couldn’t help have. Was I tired? Was I hungry? Was I still feeling the aftermath of the station samosa? I swiftly ruled out these physical causes and recognised my unease as having a psychological root. Something was bothering me. Something was making me uneasy and annoyed, which in itself was disturbing me as I felt that of all places, out of every square foot I could have landed in on the globe, surely this was the place where I should be keying in to some sublime spiritual experience, some resonant, Dharmic peace. Not mild irritation with my fellow visitors. Where was the metta!? How undharmic could it be!? If I’ve learned nothing else in my time studying the Dharma, I’ve learned that these moments of unease, or irritability, or dissatisfaction are valuable alarm bells that indicate a place I need to explore more deeply in myself. Like an ‘X marks the spot’ on a treasure map of my mind. Far from being feelings to be embarrassed or ashamed of, far from being thoughts to deny expression, they are clues and hints of an opportunity to dig a little deeper, go a little further, and learn a little more. So I went with it. I found a little gap between the meditators under the branches of the Bodhi Tree and I sat down to really observe what was going on in my mind, as well as in the world around me, calmly and without judgement. I watched the stream of people gradually making circumambulations of the shrine building and the Bodhi Tree. Chanting mantras. Prostrating and standing, stepping forward, prostrating again and repeating one arduous circuit after another. Pushing and shoving to get close enough to the tablet marking the Vajrasana to press their foreheads on the perfume oiled, gold-leaf flecked stone, to leave a coin or a note, to prostrate again. I watched the pilgrims from the east, performing habitual rituals to appease their Buddhist families, I watched the hippies from the west seeking a quick fix enlightenment on an organic coffee break from their yoga retreats, I watched wrinkled, withered monks doing the same thing they do every year; and I felt angry with them. “What good is this doing you!?” I wanted to stand up and scream. “What is the purpose of your actions? Do you even know? How on earth is this moving you closer to enlightenment? How can you be so blind, so ignorant, so repetitive, so dull?!” I felt helpless then, for them and for myself, questioning too my own reasons for being there. What was I expecting? How could I ever achieve this hugely difficult goal? Not if I meditated for every heartbeat I have remaining, or chanted with each and every breath still to come, not if I prostrated until my muscles have atrophied or offered every flower that ever grew; none of this would be enough. I felt that then so sharply and it disgusted me. Suddenly, a layer of distortion seemed to fall away from my perception and I watched the dogs scrapping in the dust, the birds bickering in the branches, the people pushing past each other to feel themselves, or be witnessed by others as just a shred closer to the transcendental and I saw this hopeless struggling in each of them to escape their suffering. The empty or over filled stomachs, the diseased or injured bodies, the anguished minds. The self-abused, the socially oppressed, the poor and in need, the rich yet dissatisfied, the internal pain, the external friction, the hurt, the sorrow, the suffering, the despairing machinations of each and every being, those present in front of me and those on the furthest reaches of the planets crust, all just desperate, so desperate to break free from the rounds of conditioned existence; and my heart simply broke. All that anger and irritation completely dissolved under a flood of compassion that found physical form in my suddenly wet cheeks. So I sat and gazed up into the branches feeling at one again with all of them and never more determined to find my way to enlightenment that I might guide them to the exit myself. ‘Hold tight’ I found myself willing every other being on the planet, for not the first time. ‘I’m not sure how or when but I’ll do it. I’ll find the way and I’ll bust us out.’ Once the flow had ebbed, I found finally beneath it the motivation to draw and at last fetched my sketchbook from my bag. I didn’t move, but settled into drawing the thing I had been staring at for maybe ten, maybe twenty, maybe thirty minutes; my sketchbook note suggests I spent nearly an hour drawing the spreading, ancient branches of the great Bodhi Tree. |

The order retreat was due to start that evening on the Triratna land. I knew, as I had been told by more than one order member, including co-leader Maitriveer Nagarjuna, whom I had got to know through NNBY, that I was welcome to attend the evening pujas to be held every night at the Mahabodhi Temple, but that as I was not yet ordained, I would not be able to join the meditations or talks. To be quite honest, it had not even occurred to me that I might participate in any of the retreat at all and as far as I was concerned it was a coincidental event that had nothing to do with my visit. However; that invitation had planted a seed of curiosity. I had no specific plans for my days and the land was a nice enough place to spend time; there was something about it that reminded me of an English garden during a particularly warm autumn. I realised that if I happened to be sitting there, enjoying the peace and quiet, absorbing the hedges and flowerbeds, the gentle calm and the clear, fresh air, if I happened to hear some of what was being said through the walls of the marquee it was being said in… well… that wasn’t exactly intruding… was it? The fact that on the second day an enormous speaker appeared outside the marquee suggested that if I wasn’t being exactly encouraged (I think it was to reduce feedback from all the equipment inside the tent, not to satisfy a greedy mitra), then I at least wasn’t eavesdropping on any guarded Dharmic secrets. Of course, this would never have been much use to me had Maitreveer not been co-leading with none other than Subhuti himself, whom, as I have mentioned in earlier writing, delivers his talks in English, with interpretation. My luck was clearly in and so, the rest of my time in Bodhgaya was basically formed around these activities; either sitting at the temple, reflecting, drawing, observing, meditating, or pitched up outside the tent for some insight into what sort of talks and meditations are shared on an order retreat. There are, of course, plenty of other temples, centres and places to visit in Bodhgaya but I didn’t feel like paying them any attention beyond their utilisation as handy navigational landmarks. All I really felt like doing was being at the Mahabodhi Temple, or listening to the Dharma in a language that was familiar to me, both in terms of linguistics and the Triratna style of teaching. In the evenings, I joined the puja with the retreatants. Some of the ritual I could enthusiastically join in with, and it was lovely to discover that I had become familiar enough with a little of the Hindi to join in the positive precepts but I had to shut up half way through; order members commit to ten ethical precepts, not the five that mitras begin on and I didn’t know all of them, in fact, the fifth seemed somehow different too, so I ended up just joining in with the first four and the little bits I was familiar with elsewhere. Though it was a comforting familiarity to feel I was practically participating, really, it was the inclusion itself that mattered. No, I may not yet have had the training and experience to fully participate in the other activities on the retreat, but still my presence, my commitment and my intention, was recognised and valued enough to be included in what for most people is the pinnacle of each day’s practice.

| I have had the recurring experience since studying Buddhism that the course, or book, or teaching I am engaged with seems to do no more than guide me along a path that I pick out for myself. I am on a well-worn trajectory that is far from accidental, yet I am supported to follow a deeply honest personal instinct, as a migrating goose in a flock independently follows a natural truth alongside others, not compelled to shape my journey to a system of given co-ordinate facts by an external, academic discipline. Wild geese do not need to ‘recalculate’ their GPS directions due to unreported road closures. I am sure that if I’ve articulated it well enough, that description will seem familiar to many. I first made this distinct observation when completing courses in Manchester and again in London, when simultaneously studying and reading The Journey and the Guide by Maitreyabandhu. Time and again, the close of a chapter or class would cause me to independently consider certain concepts, or identify particular personal issues that might at first glance appear tangential. Lo and behold; however, the very next chapter, or the topic of the next class would describe just that, sometimes subtly, sometimes quite directly, as if the author or teachers had somehow checked in on my most private thoughts and factored that in to their lesson planning. I tried to avoid interpreting this from the point of view of my conditioning around academic success but I found it to be a very affirming experience. |

Of course, you can’t really manufacture it. It just has to happen. It is certainly confidence building though and I was relieved to experience it again in Bodhgaya, despite the piecemeal and somewhat voyeuristic nature of my ‘study’. There were, for example, times when I was making notes during the main talks that I found myself so tuned in to the topic that I was practically writing down what Subhuti was saying as it came out of the speakers. Once or twice, I summarised things to myself in a hastily jotted phrase, only for him to use the same analogy in the next sentence.

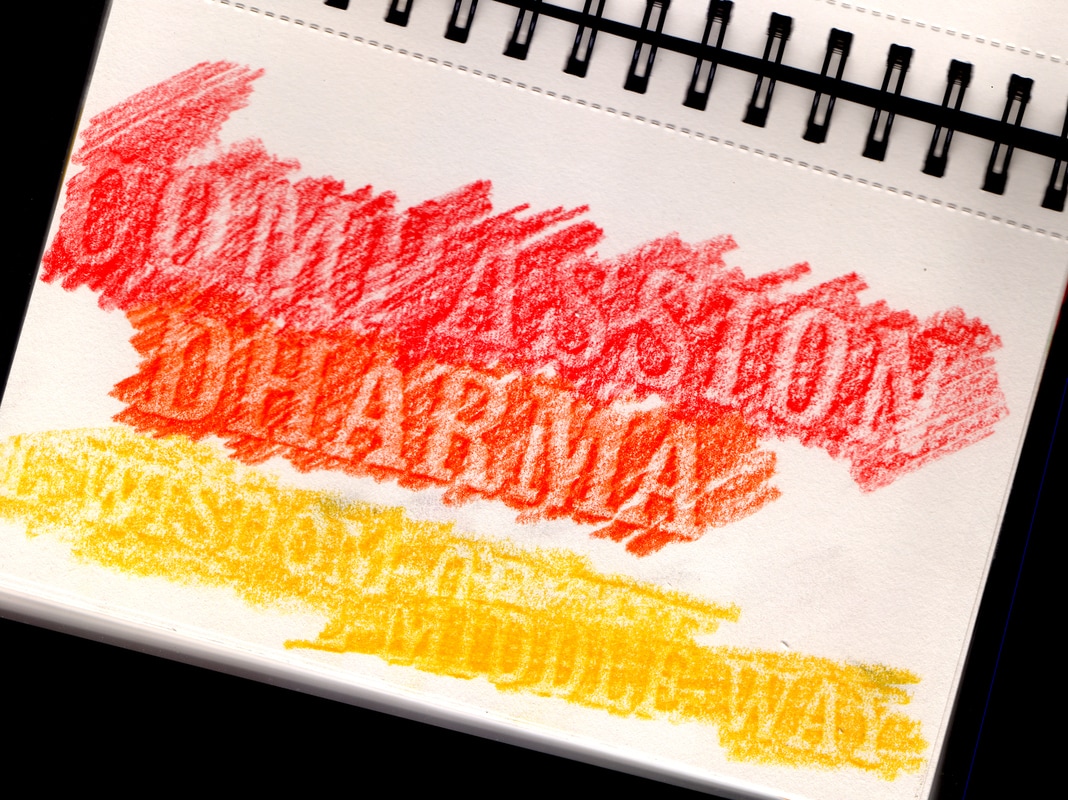

| That felt a bit like when you think you are finding your way OK based on a rather confusing map, but look up to confirm that a landmark you were hoping to see is, indeed, firmly rooted in the ground before you. ‘Yes! I get it! I’m on the right track!’ In Bodhgaya, I found a couple of particularly notable moments of this affirmative experience, the first of which served to provide me with some clarity the day after my confused feelings of anger-cum-heartbreak-cum-determination under the Bodhi Tree. The theme of the order retreat was compassion and one of the first talks Subhuti gave reflected on the cultivation of Bodhicitta. I’m currently reading into this topic further as preparation for an upcoming retreat and it’s a complex area that I don’t pretend to fully grasp, but it does inextricably link a desire to achieve Enlightenment with the purpose of benefitting all other beings, essentially due to the dissolution of the self-illusion. Once you realise, really feel that ‘you’ and ‘them’ are simply different expressions of the same being, all your actions become wise and compassionate by default because what benefits ‘you’, benefits ‘them’, what benefits ‘them’, benefits ‘you’ and there is a deep understanding of these apparently separate entities as in fact, a single coherent body. I am still definitely interacting with the world through the illusion of self, however, the fact is that I felt an incredibly intense urge to get beyond that, not so I could pat myself on the back and put my feet up with a cup of spiritual tea, listen to Nirvana (bad 90’s music joke, sorry) and enjoy a future of blissful release; but so that I knew how to get everyone else out of their suffering too. I find I am recoiling from writing these words for fear of appearing to seek approval, praise, or status. I don’t know exactly what I felt, or what it ‘means’, if it can be said to mean anything. I am not claiming to be channelling Bodichitta, nor assuming I’ve ever done so, but I couldn’t help feeling, when I heard Subhuti describe this, that I was very, very familiar with his words. ‘Yes,’ I kept thinking, ‘I know how that goes’ and my mind kept returning to my experience under the Bodhi Tree. ‘I wouldn’t have described it so eloquently myself or known to explain it in those terms,’ I thought, ‘but that’s what I felt, that’s what it was.’ |

The next evening, sitting again outside the tent in the late, amber sun (actually I think I had a better deal than those inside, quite frankly) I learned, for the first time, the Development of Bodhicitta practice of meditation. It was not one I had come across before in either my experiences in Triratna drop in classes, or on open retreats and I suspect that it’s not normally introduced until a little further down the line of study. I also suspect that a standard way of learning it would be to build up to it slowly, one stage at a time. I’m nothing if not committed though, and previous incarnations of self, have me led to develop a kind of sturdy resilience that I try and avoid feeling proud of. In other words, I have a personality that enjoys the challenge of the deep end and I am no stranger to feelings of both emotional and physical pain and discomfort. Let me at it. In the Development of Bodhicitta meditation, one begins from a strong foundation of metta, or loving kindness for oneself. From this base, you imagine that you are ‘going for refuge’, or seeking Enlightenment from the teachings and practices of Buddhism, with all other sentient beings for their benefit. From here, you build up a sense of your own unshakable commitment to this, imagined as a clear, bright, white light at your heart, alongside a sense of the suffering and unskilful actions of the other beings, seen as a dark black smoke in theirs. Now, you visualise yourself breathing in their black smoke, physically inhaling their suffering, relieving them of it in order to neutralise it in the intensity of the light of your purpose. For myself, I imagined this very visually, like when you drop ink into bleach and that staining simply fades away on contact. I found myself able to focus during this meditation and felt no ill effects. I quite enjoyed it as a new experience and I appreciated the mental aesthetics it encouraged. The next morning; however (I have long thought a good meditation is a bit like a hot chilli; you only appreciate it through the after burn), I wrote this:

‘Feeling sick today. Sick and no motivation. Yesterday, began feeling like I’ll never be able to do this. It’s too hard. I am inadequate. Oh, hi Mara. Too much work. Thinking about the analogy of the black smoke, yes, I feel polluted. Poisoned. Exhausted too. I feel like I could scream in frustration. Honestly, I feel that emotional, I feel like I’m railing against the reality of the way things are, like a slumbering teen, shouting and swearing at the caring parent who is trying to wake them up. Where is this anger from? It’s too easy. It’s just too f**cking easy to accept a bit of suffering in exchange for the pleasurable moments, to accept the occasional dissatisfaction for the comfort of impotent complacency. This Dharma sh*t is f**cking hard work. It’s painful and it’s tough and it’s messy, but once you’ve seen that it’s the only way forward, for the whole damned universe, how can you ignore it? The illusion that is me feels very emotional today.’ | Then, I wrote a poem about self-clinging and ignorance. |

In composing this post I’ve avoided, until now, spilling out great reams from my sketchbook notes and I am making genuine efforts to edit and summarise my most important experiences but these musings from the morning of February 8th still seem so rich and direct and honest that I’ve made an exception in this case. They are also by way of being an introduction to my next experience of being ‘one step ahead of the text book’. It’s perhaps not so strange that I had thought in terms of the ‘folklore’ of the Buddha’s Enlightenment, being so close to the source and surrounded by various retellings of how Mara flung arrows at the meditating Siddhartha in an attempt to distract him from his task. I did genuinely have a sense that my feelings of rage, inadequacy, irritation and discomfort were no more than some kind of counterintuitive force (a bit of my own head no doubt, anthropomorphised as Mara), dragging me away from the effort of commitment to serving the Dharma, and, being a poetic type who revels in analogy, I’d already couched them in terms of being akin to Mara’s arrows. It felt very ‘right’ then, that Subhuti’s talk that afternoon took the next part of this same story to explain how to deal with them. The story continues that the determined aura of the meditating Buddha-to-be is strong enough for the arrows to be transformed into flowers as soon as they meet it, raining blossoms instead of threat. This, Subhuti explained, is something we can do in our own lives.

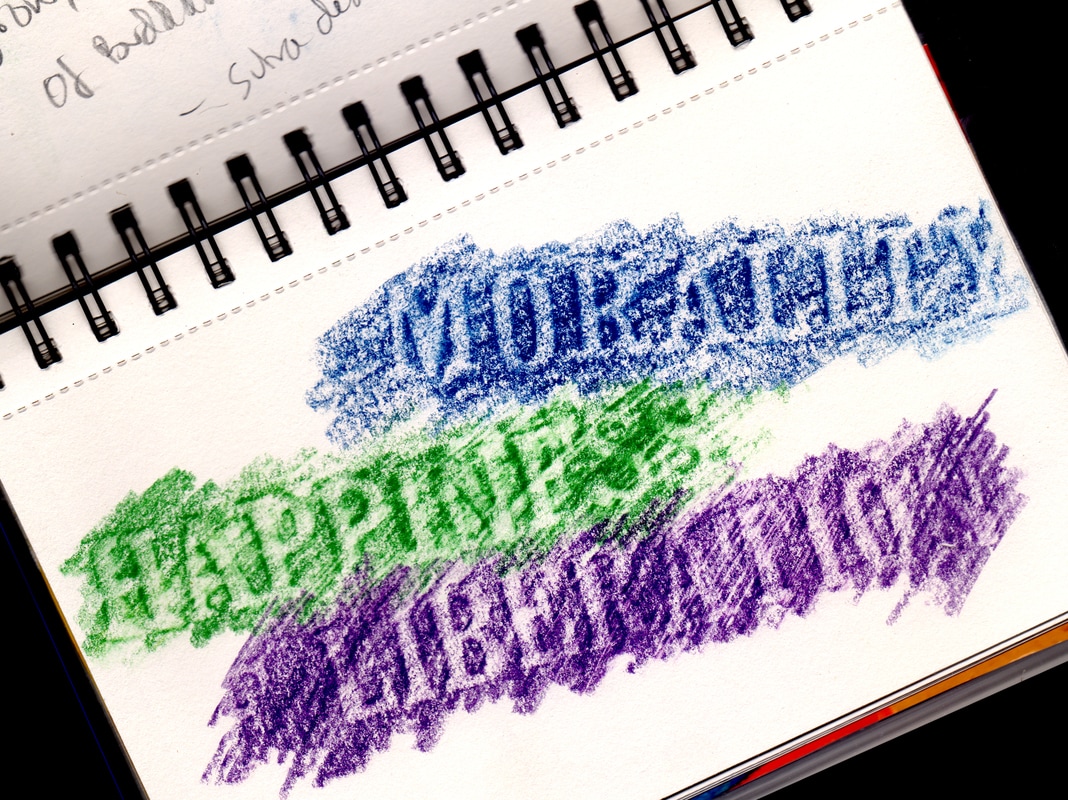

| When we notice moments of irritation, pain, unhappiness, anything serving as a distraction from our practice, we can take the time to acknowledge it, be aware of it and respond mindfully, transforming it instead into a flower of compassion, be that compassion towards ourselves or others. We can recognise the hate, or anger, or fear in the world and we can see past the apparent threat to the underlying suffering that causes it and respond to that suffering lovingly, rather than react to the unpleasant experience in a way that fuels or exacerbates it. Yet another experience where it seemed my thoughts had been responded to, very directly, very personally. If I believed in an interventionist god, I’d certainly have believed my prayers answered. The next morning, still feeling unsettled and fractious, I began a little creative project that I maintained for the rest of my stay, in which I acknowledged such moments as ‘arrows’ and drew them as seeds, from which I visually described the ‘flower of compassion’ bursting. I hoped that the time I took to put pencil to paper and think about what form the flower from that particular seed would take, could be the time in which the reactive feeling would subside and allow me to respond more skilfully. Sometimes it certainly did, sometimes it took a little more work, but I quite enjoyed the activity and though I’ve not yet carried it further, it seems like it might itself be the seed of a wider, deeper project. |

The Development of Bodhicitta meditation was alternated (aside from the basis of the very familiar Metta Bhavana and Mindfulness of Breathing meditations, which were also included), with one other that was slightly more familiar to me. I had read about the Six Element practice, in which one works systematically through each ‘element’ of what appears to be the fixed self to contemplate its transience. For example, beginning with Earth, we develop an awareness of all that is earthy, or solid about us; our bones, flesh, organs, the food we have consumed, and we remind ourselves that our bodies are made from cells that were not with us when we were born and will continue to be refreshed and replaced until we die, when our final materialisation will return again to earth. The atoms that make our cells do not belong to us, they are part of a system of process including all organic matter. We think then of the Water element, our bodily fluids, all passing through us in a daily cycle of drinking and urinating, exhaling, sweating. The Air, our breath, passing in and out of us as the oxygen is absorbed, the carbon dioxide released. Our body heat and energy, the Fire element, generated by our metabolism or borrowed from the sun. In addition to these more traditional elements, we progress then to the Space we occupy temporarily, moving through it, never fixed, and finally consciousness, where we consider the impossibility of fixing the origin of this to anywhere permanent. I am conscious of a pain in my shoulder, but my consciousness does not originate there. I am aware of sense impressions from the outside world, yet my consciousness does not reside in the throat of the bird whose song I can hear, or the released chlorophyll of the grass clippings I can smell, or the current of the breeze I can feel on my face.

| The purpose of this meditation is to try and realise the illusive falsehood of a fixed self on a deeper level than the surface fact. we know we are changing, developing, learning, aging and progressing, until we one day die but we can’t help behaving like this only applies to other people. The Six Element meditation aims to bring us in to a closer, deeper realisation of our own impermanence. I first read about it some months back but I did not feel able to attempt it without guidance, I did not understand it or its purpose well enough to know where I was going with it. I was actually quite excited when I heard it would be included in the retreat and despite managing to fall asleep in my first attempt, I enjoyed it thereafter. I found something very reassuring, very comforting, about feeling I was really only responsible for guiding a collection of ‘stuff’ through a temporary experience that would one day cease to be my problem. That might not be a particularly healthy way to view impermanence and I don’t want to sway too far towards the nihilist or use it as an excuse to deny responsibility for my actions but hey, as aforementioned, this Dharma sh*t is f**king hard work, so I’m gonna take my breaks where I can get ‘em. Pleasant as that was, actually, the most useful thing I derived from the experience was an actual felt sense of my consciousness being no longer limited in my perception to this coagulation of flesh I call ‘me’. I found, particularly through the sense of sound, which was interesting as a primarily visual person, that if I angled my thoughts in the right direction, I could really feel that ‘I’ extended beyond my body in an imagined sphere that stretched at least as far as the origin of sounds I was aware of. I’m aware as I cobble those words together that I don’t yet have a way to properly articulate it. I’m not sure if that’s a sense others would corroborate, I’ve not had the chance to discuss it with anyone yet, but the pleasant thing is, I have been able to easily revisit it in subsequent meditations. I think as far as ‘expanding one’s mind’ goes, I’ve done no more than swell my ball-bearing scale consciousness to the size of a small marble, but it’s been an interesting development to my methods of experiencing myself as a part of the wider universe. |

Interestingly, my reflection that ‘I’ve not had a chance to discuss it with anyone yet’, is perhaps the most important thing to mention in addition to the intellectual learning, about my time ‘on the edges’ of the retreat. No doubt there’s nourishment to be found in gathering the scraps dropped from a table but one can’t be guaranteed the same balanced meal as the guests, nor can one benefit from the dinner party chatter. If I struggled with the week, or the content I absorbed by osmosis, it was at least in part due to that semi-solitary nature and the lack of opportunity to ‘unpack’ my experiences as part of a peer group, something I shall now value even more on my next retreat. I benefitted greatly and I feel deep gratitude that I was able to do so, but I have had cause to really understand the difference between being on a retreat and studying by one’s self. In terms of the Three Jewels, what was missing of course, was Sangha. Actually, as I write that, I realise it was far from missing really, and the fact that my conspicuous scurrying about on the edges was tolerated in the first place is some evidence of that, but it’s a subtle manifestation and not of the same intensity as actually having the spiritual fellowship of shared practice. Nor have I taken lightly that which I received. Even if I have described it as crumbs from a table, still I know there are others starving. I’m all too aware that many of the order members who had paid to attend what I got a lot of for free, will have been scarce able to afford it and will perhaps be able to attend such gatherings only sporadically for that reason. If anyone reading this is thinking that my Dharmic eavesdropping sounds a bit too much like ‘taking the not given’, please rest assured that since I returned to the UK, I have set up a standing order to make monthly donations to the Indian Dhamma Trust, who work to support people otherwise unable to access the teachings or train for ordination in to the Triratna movement.

| Anyway, just as my body is merely borrowing its elements from the universe, my mind is only borrowing the knowledge I gained. I will, as an aspiring servant of the Dharma, be gladly utilising all my learning for the benefit of others at every possible opportunity. Though I had succeeded somewhat in avoiding a fixed expectation of the trip, I suppose it was only natural that I had some hopes or dreams of encountering a deeply moving, transformational spiritual experience that left me on some kind of elevated plane of consciousness. Perhaps I did find this on a more subtle level, I certainly learned a lot from the talks and I benefitted from the time and spaciousness, from my reflections at the temple and in meditation during the week. I also reengaged with a dormant creative practice in my sketchbook and in a series of photographs taken in the temple complex. I think the true value of the experience will be found in the subtleties though, not in the features. It’s in how I take that learning, those moments of realisation in the conditions conducive to their arrival, and apply it to my daily routine in more mundane surroundings that will decide how fruitful my time at Bodhgaya was. Like a random battery discovered at the back of the kitchen drawer, perhaps the spiritual energy I gained from the trip will not be obvious until I have cause to discharge its energy to an appropriate application. |

So no, as I wandered the land of the Buddha's Enlightenment, I didn’t find my ultimate release from suffering the rounds of conditioned existence. I did not achieve Nirvana under the Bodhi Tree. But as our teacher, Sangharakshita has identified:

‘Our everyday life may be pleasurable or painful; wildly ecstatic or unbearably agonising; or just plain dull and boring much of the time. But it is here, in the midst of all these experiences, good, bad and indifferent – and nowhere else – that Enlightenment is to be attained.’

The photographs used in this post are from a new series titled At the Foot of the Diamond Throne

RSS Feed

RSS Feed