We had nothing planned until the evening ‘checking in’ with the girls today and I have been feeling somewhat snotty (I’m assuming this to be an initial reaction to alien atmospherics), so I decided to take it gently and do some Dhamma (Indian version of Dharma) study after our morning meditation. After Shakyajata had refreshed my memory of the Four Reminders (OK, so that was a minor bit of lesson preparation, but still counted), I listened to a talk I had downloaded by Subhuti on the Five Niyamas. It’s pretty fundamental Buddhism but is perhaps a little weighty to make any detail appropriate on this platform so I’ll leave you to research that further if it inspires you. However, it’s all linked to the concepts of conditioned co-production, which is perhaps best explained with a phrase that may be familiar;

This being, that becomes; This could all get very deep, very fast, but whilst I have no desire to inflict that on you, it did seem to set the tone for my day and I began considering the conditions that have led me to be here. This is on a practical level, the unfolding of events that have resulted in my arrival in India, as well as from a potentially more mysterious angle as I reflected on Subhuti’s references to structured patterns in reality. These, he explains, mean that your intentions modify the world around you and may affect what comes back to you, possibly even across lifetimes. Now, it is important here to reference the fourth reminder; ‘However I act, life always has difficulties, no-one can control it all.’ This is not saying that ‘bad things happen to good people’ (sure, they do, but they happen to good people too), nor that if you experience suffering in your life it is somehow, distantly your fault. |

The young people at Aryaloka have been brought up in communities who for generations have been oppressed by a different approach to Khamma (Karma), with the belief that to be born outside the privileges of the caste system is simply your lot in life due to your past unskilful actions. This is not how Buddhism interprets it, certainly not in Triratna, but still we accept that our conscious, deliberate actions, affect a natural process that governs our experience of everything around us. The third reminder tells us that ‘The karma I create shapes the course of my life. (Actions have consequences)‘, which is the essence of this concept and led me to again consider the analogy of the ‘path’ by which we travel through life.

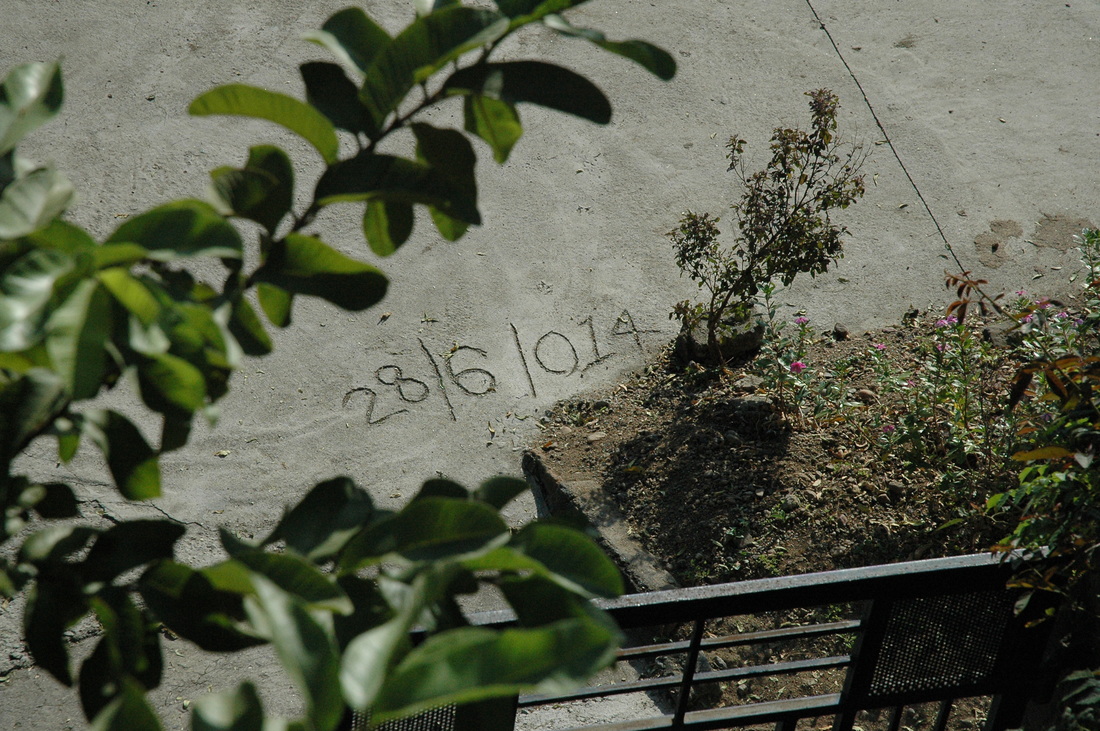

On the day I arrived, I asked Aryaketu why the date of June 28th is inscribed into the cement outside his house. That’s my birthday, so it caught my attention. He explained that was the date the road had been laid.

On the day I arrived, I asked Aryaketu why the date of June 28th is inscribed into the cement outside his house. That’s my birthday, so it caught my attention. He explained that was the date the road had been laid.

| Now, some superstitious types might latch on to that as an indication of some force of fate at work, whilst more logical types might manage a wry smile as they explained how we seek patterns in things to explain the universe and that any meaning in these are merely human inventions. I don’t think Buddhist teaching would disagree with that statement, we are taught that we create the world with our minds after all; however, it would not dismiss a more mysterious perspective either. We know reality is ordered and things do not arise randomly. Whatever thoughts it’s poetic at least that my birthday is inscribed in the path, or ‘magga’ that leads to Aryaloka. |

At 4pm, we gathered the girls into the shrine room (it was cooler than the classroom) for a group chat, to ‘check in’ and share how we were all feeling. This is a common practice in Triratna teams and a really useful way to build trust and mutual awareness. Sheetal kindly interpreted for us, seamlessly switching between Hindi and English. As well as providing an opportunity for us to get to know the group a little better, it was also nice for Shakyajata and me to rejoice a little in each other’s merits and to publically recognise things we value in one another. The girls’ stories were on a whole different level though and they seemed very keen to share them with us. Each described her initial apprehensions around leaving her home and family with similar sentiments yet clearly differing flavours of individuality and despite being one stage removed by the translation, it was easy to get a palpable sense of their longing for opportunity and freedom from an otherwise bleak future. None of the girls have been away from their homes before and in the close-knit familial culture of India, this is in its self a very big deal. Most of them have come to learn computing skills having never before even set her eyes on a computer, a fact I think pretty much every British teenager would find quite unimaginable. Several girls described the long, arduous train journeys from their home states as the first time they had even been on a train. UK commuters (myself included) may grumble about the aftermath of privatisation but I reckon we’d be silenced pretty swiftly by five hours in an Indian sleeper berth, a pleasure I’ve yet to savour. These journeys are especially unsafe for women, even those who aren’t as vulnerable as an eighteen year old independently travelling for the first time. Each girl had her own story of overcoming significant but natural anxieties to get to Aryaloka, but each concluded by expressing how she had since discovered such genuine joy and optimism that it was easy to forget the reality of the backgrounds from which they have come. Hemlata’s concluding tale of a determination to travel completely alone, (even having convinced her mother to allow it!) when it seemed her friend, Pinky, would not come after all, simply underlines the sheer yearning and determination of these intrepid, yet gentle souls. It wasn’t until she went on to describe how she had called her mother to say she mustn’t worry for her safety as she had found ‘a new family’ at Aryaloka that I realised just how much I identified with their stories.

| My being here has come about as the result of my own suffering, albeit of a very different flavour, and I too have recently sent messages to a (mildly) worrying mum to let her know I am safe and cared for after a long journey. I too, have committed to the longest time away from home I shall ever have known, in a foreign place and with little knowledge of what awaits. Happily, I can also share that deep sense of relief, joy and eager anticipation of what is to come that Hemlata and her new sisters all communicated today. I too have found a new family, and while I may think of those I have left behind, I am safe in the knowledge that I am also now forging new friendships for life. |

Tomorrow, we face the bumpy, dusty, crowded bus ride up the Kamptee Road to the centre where the young men live and study and I am sure we shall be treated to expressions of much the same degree of commitment and motivation to self-improve. Though we may, or may not have arrived at our current experiences of life as a result of our own actions, what is true is that the actions we take now will certainly affect our experiences of the future. These young people seem instinctively aware of this, be it Dhamma teaching or not and I’m so keen to meet yet more of them that I’m even looking forward to donning my dust mask and getting on that rickety bus!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed