The experiences are coming in so thick and fast here at Aryaloka that it seems hard to keep on top of the priorities in so far as my aims for this blog. I set it up primarily to record, but then also communicate my time exploring the unfamiliar geographical and psychological landscape of my new position as a volunteer teacher in a foreign social project. This is because I could see before I even applied for the visa that the new perspectives I was bound to encounter could be of value to many people, if only I could articulate them. I hope my western friends and contacts may be able to understand their privileges and challenges with more clarity in a global context and believe the work being undertaken by my Indian colleagues to be anyway so very deserving of recognition, broadcast and celebration. It can be a complex operation to separate this genuine desire to broaden horizons from the almost voyeuristic impulses of the travelling photographer; look at this photo of a funny crisp packet, this description of a strange social norm, this ‘tragic’ symptom of disadvantage and poverty. I shall be clear; however, that whilst none of my observations are intended to judge, condemn or laud either my own or another’s culture, I am aware there will be times when I shall find it difficult to avoid some apparent poignancy.

| The people I have met so far though, are far from in need of western sentimental sympathy and in fact we could learn a great deal from their resolve, their generosity and their extensive application of remarkable energy and steadfast determination to achieve what must done. They appear to be, in many respects far happier and more grateful for far less than many of the most challenged British citizens. Things have, of course, improved dramatically for many local people in recent decades, due in part to the reason for our attendance last night at the Deekshabhoomi, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the mass conversion to Buddhism of Dr Ambedkar and his followers. This genuine social liberation and increased prosperity found in education and spiritual development is not just a credit to a remarkable man and those who continue his work, but an ongoing trend to be treasured, shared and cultivated. We travelled to the Deekshabhoomi by auto rickshaw, an experience enough in its own right, as the father of our friend and ex-Aryaloka student Neha, battled through fleets of oncoming traffic and intrepidly held his own amidst entire families clinging to scooters, impatient cars, and streams of the large, brightly decorated lorries that are such a feature of the dusty Kamptee Road. Neha’s ‘Papa’ is fortunate today; as a result of the generosity of many donors, it was possible to purchase the tatty, beat-up vehicle and relieve him of the back-breaking work of endless daily pedalling. My friends and I might have been one of his lighter loads too, though this has not eradicated the health risks of his profession; the pollution is enough to cause western visitors to seek the limited protection of dust masks, even for a thirty minute journey, and with an unpredictable response rate to what rules of the road do exist, traffic accidents are common. It was busy as expected when we arrived at the road leading to the Deekshabhoomi (literally ‘conversion ground’) and it was not for the meek or faint hearted foreigner to walk with purpose and conviction to the entrance in the sea of curious stares. The soon to be familiar call of ‘Please, Ma’am, just one photo?’ quickly started up and whilst I was sorry in some respects that I could not photograph inside the monument, |

it did at least provide an excuse to decline without appearing unfriendly. Unfortunately; however, using this rule as protection from the lens did not prevent an awareness of the crowd building outside, eagerly awaiting our exit from the stupa with camera phones at the ready for ‘just one selfie with my kids!” As a result, it was hard to focus or really develop a sense of appreciation for the purpose of the reliquary; the ashes of Dr Ambedkar himself, in a grand cask, under a glass dome and set on a highly decorated platform at the centre of the marble hall. Still, we managed a brief moment taking this in before the encroaching tide of devotees washed us back out into the night. We had hoped to conduct a short puja in the hall, and there were indeed a few people resolutely chanting in small groups or pairs, at the side of the walkway, but we were causing enough of a distraction as it was, so Shakyajata wisely guided us to a spot outside where we perched on a wall as she bravely lead our group in chanting the refuges and precepts in Hindi and English. This at least provided an opportunity for people to come and have a good stare and snap away to their hearts content, which made me feel far less impolite for having refused earlier requests while taking shots of my own. It occurred to me as we took a short meditative pause following the chant, that less than a year ago I was still privately struggling to come to terms with my own spiritual identity and yet now, here I was, practicing more publically then I could ever have anticipated, in the land of the origination of my faith. Never say never. After this, we took a stroll around the bustling complex, taking in the Bodhi tree, part of an intricate web of stories regarding the generations grown from seeds of the original tree under which Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, is said to have achieved Enlightenment.

| In the small shrine room, we were approached by a polite but curious monk whom, my friend interpreted for me, had expressed gratitude to us as British visitors for the role of the Empire in preserving Buddhist temples and relics from destruction by Hindu oppressors. This gratitude was a new experience for me; I have grown up, as have many, with a clinging sense of guilt for the colonial activities of the British Empire, so I found this perspective pleasantly refreshing. After some time to catch up, it was time to weave our way back down the crowded street, flanked by temporary market stalls of all kinds, to await our collection by Neha’s papa, who, we were assured, was very close by in the jam of traffic. Some street snacks of hot roasted peanuts and sweet sesame brittle fuelled our continued conversation until it was time to dive across the road where he waited for us, unflinchingly bearing the brunt of a traffic policeman’s aggression for having stopped where he should not. For the first time I began to genuinely fear for our safety as the official punctuated angry shouts by jabbing at our poor driver, even pulling at his shirt to drag him from the seat. Thankfully, through the placations of his children, the swift physical intervention of Shakyajata, and his sheer determination to achieve a quick getaway, we managed to escape the frustrated wrath of the law and sputtered off into the traffic once more, leaving our friends behind with scant farewell. |

Upon our safe arrival back at Aryaloka, it seemed at least ungrateful, if not quite disrespectful to pay this man for both our journeys with the equivalent of about £7.50, however I was assured this was quite generous and he certainly seemed surprised when we refused any change. We left him also with the remains of our snacks; he had a long night of work ahead of him and it was unlikely that he would have had any meal break in what had already been a hard shift.

The commitment of our hosts to our wellbeing did not stop at the means to travel, against all odds, to and from the Deekshabhoomi though, and as soon as we were through the door, Sheetal began cooking for us, despite the late hour. She did at least allow us to help chop the vegetables for a delicious pilau, which we ate with gratitude after a tiring trip. After this dinner, Shakyajata retired, and I was considering a similar course of action when Sheetal sat down with a pile of papers and turned on her laptop. She explained that she had not found time during the day to enter the data from the student’s application forms onto the system operated by the government agency who certify the qualifications, and that the deadline for doing so without incurring a fine was the next day. Though the specifics of the context may be alien to me, the situation itself was almost comfortingly familiar and I was glad she was receptive to my further offer of help. I don’t think it took too long for her to show me how to use the software to infill the necessary information for upload and I consider myself to be quite a fast learner as well as a reasonably speedy typist, but still the job took until nearly midnight. I was glad to do this though, as Sheetal then had time to rub some Ralgex-like smelling ayurvedic ointment on to sore legs to ease her arthritis, which she explained without a trace of self-pity, was the result of a dietary calcium deficiency.

The commitment of our hosts to our wellbeing did not stop at the means to travel, against all odds, to and from the Deekshabhoomi though, and as soon as we were through the door, Sheetal began cooking for us, despite the late hour. She did at least allow us to help chop the vegetables for a delicious pilau, which we ate with gratitude after a tiring trip. After this dinner, Shakyajata retired, and I was considering a similar course of action when Sheetal sat down with a pile of papers and turned on her laptop. She explained that she had not found time during the day to enter the data from the student’s application forms onto the system operated by the government agency who certify the qualifications, and that the deadline for doing so without incurring a fine was the next day. Though the specifics of the context may be alien to me, the situation itself was almost comfortingly familiar and I was glad she was receptive to my further offer of help. I don’t think it took too long for her to show me how to use the software to infill the necessary information for upload and I consider myself to be quite a fast learner as well as a reasonably speedy typist, but still the job took until nearly midnight. I was glad to do this though, as Sheetal then had time to rub some Ralgex-like smelling ayurvedic ointment on to sore legs to ease her arthritis, which she explained without a trace of self-pity, was the result of a dietary calcium deficiency.

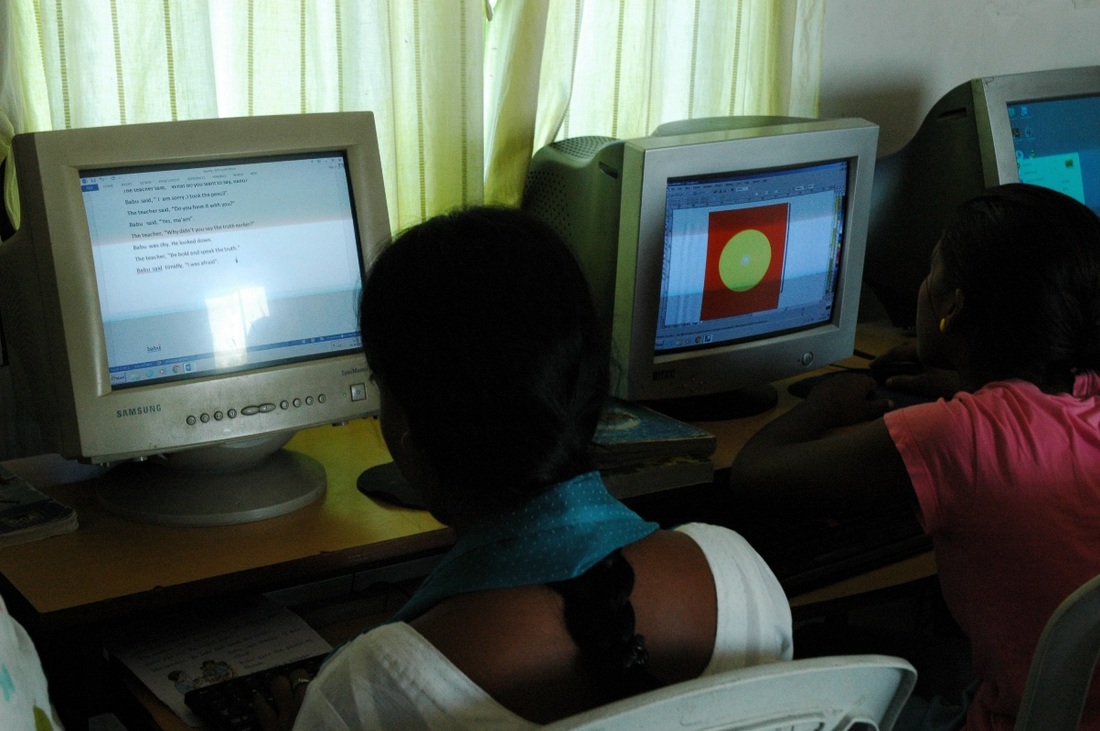

| I could easily leave it there as enough of an update and it’s hardly surprising that after such an evening our plans for Saturday morning became somewhat derailed by our fatigue. There’s more to say of course; we taught our first class on Saturday afternoon! In the morning, we delayed our planned meditation and postponed a trip to nearby Nagaloka Centre, until later in the day, opting instead for some impromptu Dharma study and a little more rest. After meditating, we snuck in at the back of the class to see what the girls were doing. Some were typing out passages of English text, while others began familiarising themselves with Corel Draw, a drawing programme I have not used since my days experimenting with the laser cutter on my MA in Manchester. We also checked up on the girls’ living space; a small room that sleeps up to ten that Shakyjata was disappointed had not been re painted since last year. She was pleased though to see that the girls appeared to be keeping the kitchen and toilet facilities clean and tidy. We planned an introductory session before lunch and then rested further until meeting at four for the first English class. When we returned for this in the afternoon, the girls were quick to leap from their plastic garden chairs and leave the dusty old CRT monitors to form a circle in front of the board, which one young woman carefully cleaned before the start. The first task, making and displaying name badges, was soon followed by the predictable group introductions with “My name is ______________” written clearly on the board. We then progressed through a series of phrases communicating personal information; our ages, the occupations of our parents, numbers of brothers and sisters, building on each in complexity and sometimes testing memories by linking phrases and removing the text from the board. My favourite part of the session was at the end, when having been finally allowed to copy the written text from the board, the girls were so eager to show us their books for corrections to their fastidious handwriting. The opportunity this gave for genuine interaction was a delight and so we picked up on various errors such as the capitalisation of proper nouns with a grateful acceptance from a group of young women so hungry for knowledge and so ready and able to learn, if only someone would teach them. This, of course, being far from my experience of sullen British teens, often attending under duress and defensive at a flash as soon as they are questioned or corrected. |

| I’m not yet sure how I feel about the contrasts between both the learning environment and attitude of the students in my UK and Indian roles and think it would be wise to spend some more time becoming acquainted with my new environment and assimilating the experiences before making too many comments but I can certainly tell it’s going to be a very different experience. Needless to say, although Sunday is supposed to be their day off, I am very much looking forward to meeting the group again tomorrow evening for a ‘checking in’ workshop session, when we hope to learn more about the group, at a deeper level than the initial personal facts. |

After such a successful class, the first time I have stood in front of a whiteboard for 15 months, I felt relieved and energised, as I think did Shakyajata, so we made the most of the cool evening air to stroll through the village to Nagaloka before dinner. After so many days of relative physical inactivity, it felt good to gently stretch the legs in the gathering dusk. As well as our group chat with the girls tomorrow, we hope to run similar session with the boys group on Monday, when we hope to have a bit more energy to tackle the bus into town, where they are resident. I can’t say the prospect of traveling there is stimulating my appetite for exploration as much as I’d have expected but I think this is largely to do with the only physical ill affect I’m currently aware of; a rather sore throat! I think a combination of dry air, dust and smog is responsible for the mild cold-like symptoms, but I’m confident that these will settle in time, when I’ve had a week or two to acclimatise. There’s plenty to distract me from it in any case and I’ve been very comfortable so far with no sign yet of the apparently inevitable ‘Delhi Belly’, though since I have been lucky so far to enjoy only good, home cooking, I’m far from complacent about that!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed